Timothy West | The Times | October 1996

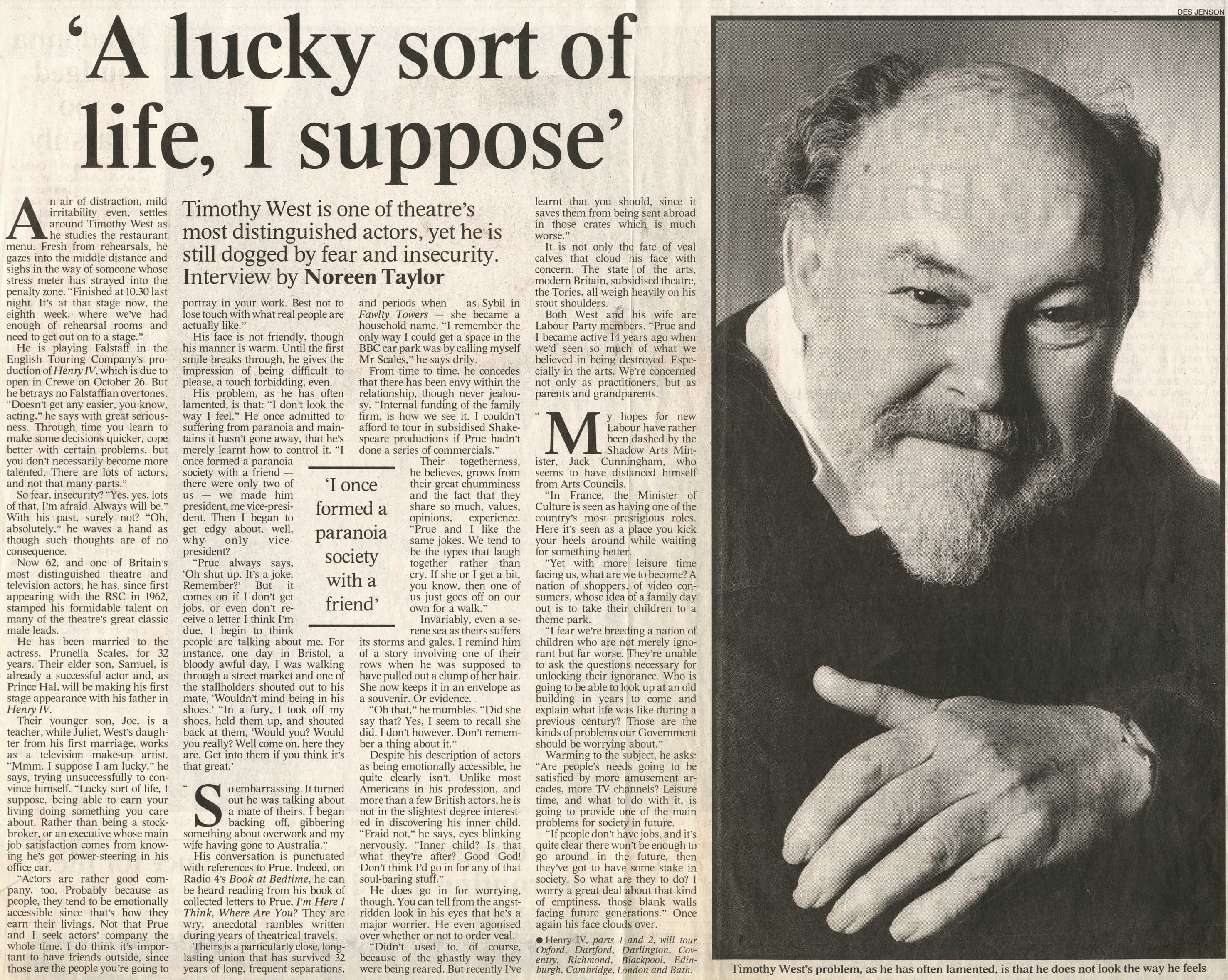

An air of distraction, mild irritability even, settles around Timothy West as he studies the restaurant menu. Fresh from rehearsals, he gazes into the middle distance and sighs in the way of someone whose stress meter has strayed into the penalty zone.

An air of distraction, mild irritability even, settles around Timothy West as he studies the restaurant menu. Fresh from rehearsals, he gazes into the middle distance and sighs in the way of someone whose stress meter has strayed into the penalty zone.

“Finished at 10.30 last night. It’s at that stage now, the eighth week, where we’ve had enough of rehearsal rooms and need to get out on to a stage.” He is playing Falstaff in the English Touring Company’s production of Henry IV, which is due to open in Crewe on October 26. But he betrays no Falstaffian overtones.

“Doesn’t get any easier, you know, acting,” he says with great seriousness. “Through time you learn to make some decisions quicker, cope better with certain problems, but you don’t necessarily become more talented. There are lots of actors, and not that many parts.”

So fear, insecurity? “Yes, yes, lots of that, I’m afraid. Always will be.” With his past, surely not? “Oh, absolutely,” he waves a hand as though such thoughts are of no consequence. Now 62, and one of Britain’s most distinguished theatre and television actors, he has, since first appearing with the RSC in 1962, stamped his formidable talent on many of the theatre’s great classic male leads.

He has been married to the actress, Prunella Scales, for 32 years. Their elder son, Samuel, is already a successful actor and, as Prince Hal, will be making his first stage appearance with his father in Henry IV.

Their younger son, Joe, is a teacher, while Juliet, West’s daughter from his first marriage, works as a television make-up artist. “Mmm. I suppose I am lucky,” he says, trying unsuccessfully to convince himself. “Lucky sort of life, I suppose, being able to earn your living doing something you care about. Rather than being a stockbroker, or an executive whose main job satisfaction comes from knowing he’s got power-steering in his office car.

“Actors are rather good company, too. Probably because as people, they tend to be emotionally accessible since that’s how they earn their livings. Not that Prue and I seek actors’ company the whole time. I do think it’s important to have friends outside, since those are the people you’re going to portray in your work. Best not to lose touch with what real people are actually like.”

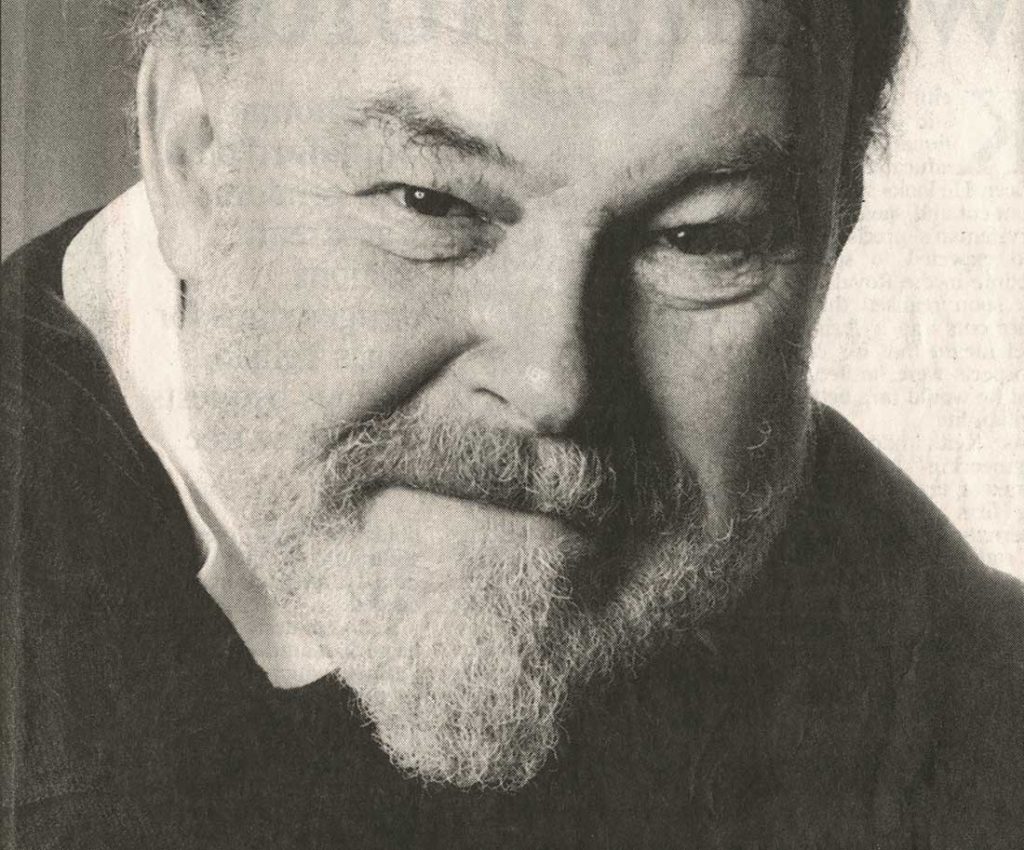

His face is not friendly, though his manner is warm. Until the first smile breaks through, he gives the impression of being difficult to please, a touch forbidding, even. His problem, as he has often lamented, is that “I don’t look the way I feel.”

He once admitted to suffering from paranoia and maintains it hasn’t gone away, that he’s merely learnt how to control it. “I once formed a paranoia society with a friend – there were only two of us – we made him president, me vice-president. Then I began to get edgy about, well, why only vice-president? Prue always says, ‘Oh shut up. It’s a joke. Remember?’

“But it comes on if I don’t get jobs, or even don’t receive a letter I think I’m due. I begin to think people are talking about me. For instance, one day in Bristol, a bloody awful day, I was walking through a street market and one of the stall-holders shouted out to his mate, ‘Wouldn’t mind being in his shoes.’

“In a fury, I took off my shoes, held them up, and shouted back at them, ‘Would you? Would you really? Well come on, here they are. Get into them if you think it’s that great.’ So embarrassing. It turned out he was talking about a mate of theirs. I began backing off, gibbering something about overwork and my wife having gone to Australia.”

His conversation is punctuated with references to Prue. Indeed, on Radio 4’sBook at Bedtime, he can be heard reading from his book of collected letters to Prue, I’m Here I Think, Where Are You? They are wry, anecdotal rambles written during periods of theatrical travels.

Theirs is a particularly close, long-lasting union that has survived 32 years of long, frequent separations and periods when – as SybilinFawlty Towers – she became a household name. “I remember the only way I could get a space in the BBC car park was by calling myself Mr Scales,” he says drily.

From time to time, he concedes that there has been envy within the relationship, though never jealousy. “Internal funding of the family firm, is how we see it. I couldn’t afford to tour in subsidised Shakespeare productions if Prue hadn’t done a series of commercials.”

Their togetherness, he believes, grows from their great chumminess and the fact that they share so much, values, opinions, experience. “Prue and I like the same jokes. We tend to be the types that laugh together rather than cry. If she or I get a bit, you know, then one of us just goes off on our own for a walk.”

Invariably, even a serene sea as theirs suffers its storms and gales. I remind him of a story involving one of their rows when he was supposed to have pulled out a clump of her hair. She now keeps it in an envelope as a souvenir. Or evidence.

“Oh that,” he mumbles. “Did she say that? Yes, I seem to recall she did. I don’t however. Don’t remember a thing about it.”

Despite his description of actors as being emotionally accessible, he quite clearly isn’t. Unlike most Americans in his profession, and more than a few British actors, he is not in the slightest degree interested in discovering his inner child. “Fraid not,” he says, eyes blinking nervously. “Inner child? Is that what they’re after? Good God! Don’t think I’d go in for any of that soul-baring stuff.”

He does go in for worrying, though. You can tell from the angst-ridden look in his eyes that he’s a major worrier. He even agonised over whether or not to order veal.

“Didn’t used to, of course, because of the ghastly way they were being reared. But recently I’ve learnt that you should, since it saves them from being sent abroad in those crates which is much worse.”

It is not only the fate of veal calves that cloud his face with concern. The state of the arts, modern Britain, subsidised theatre, the Tories, all weigh heavily on his stout shoulders. Both West and his wife are Labour Party members.

“Prue and I became active 14 years ago when we’d seen so much of what we believed in being destroyed. Especially in the arts. We’re concerned not only as practitioners, but as parents and grandparents. My hopes for new Labour have rather been dashed by the Shadow Arts Minister, Jack Cunningham, who seems to have distanced himself from Arts Councils.

“In France, the Minister of Culture is seen as having one of the country’s most prestigious roles. Here it’s seen as a place you kick your heels around while waiting for something better. Yet with more leisure time facing us, what are we to become? A nation of shoppers, of video consumers, whose idea of a family day out is to take their children to a theme park.

“I fear we’re breeding a nation of children who are not merely ignorant but far worse. They’re unable to ask the questions necessary for unlocking their ignorance. Who is going to be able to look up at an old building in years to come and explain what life was like during a previous century? Those are the kinds of problems our Government should be worrying about.”

Warming to the subject, he asks: “Are people’s needs going to be satisfied by more amusement arcades, more TV channels? Leisure time, and what to do with it, is going to provide one of the main problems for society in future.

“If people don’t have jobs, and it’s quite clear there won’t be enough to go around in the future, then they’ve got to have some stake in society. So what are they to do? I worry a great deal about that kind of emptiness, those blank walls facing future generations.”

Once again, his face clouds over.