John Peel | The Times | December 1996

Legendary disc jockey! A Radio One institution! A Sixties survivor who still counts! A Past-it Pillar of Post-Punk Society! At 57, John Peel is naturally rather resistant to the hackneyed tags that tend to accompany his name.

Legendary disc jockey! A Radio One institution! A Sixties survivor who still counts! A Past-it Pillar of Post-Punk Society! At 57, John Peel is naturally rather resistant to the hackneyed tags that tend to accompany his name.

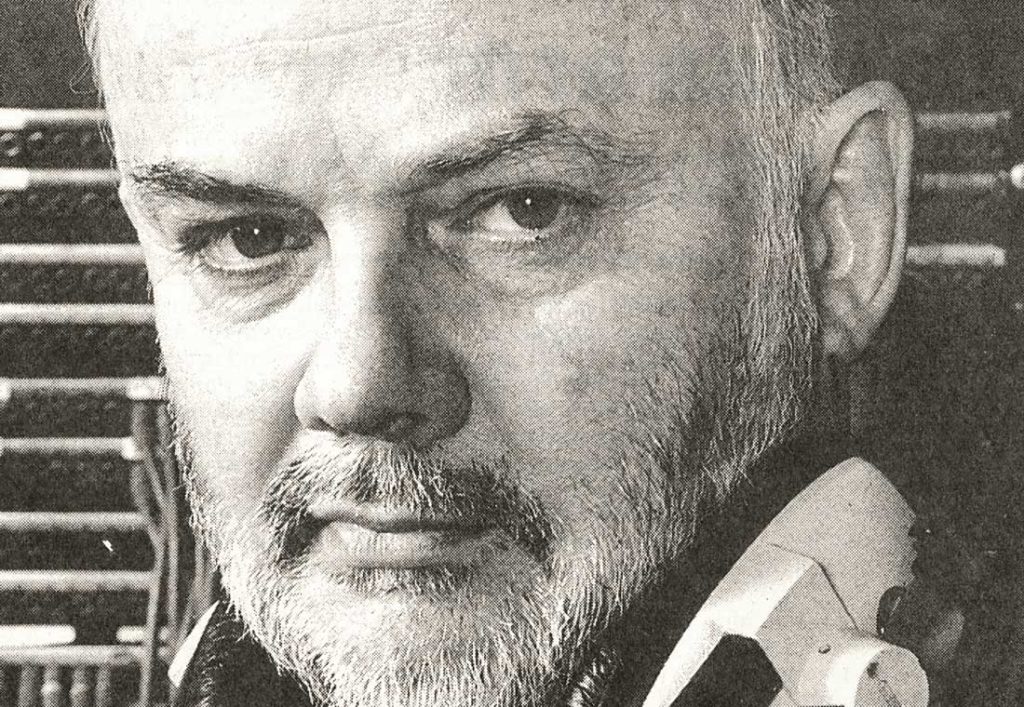

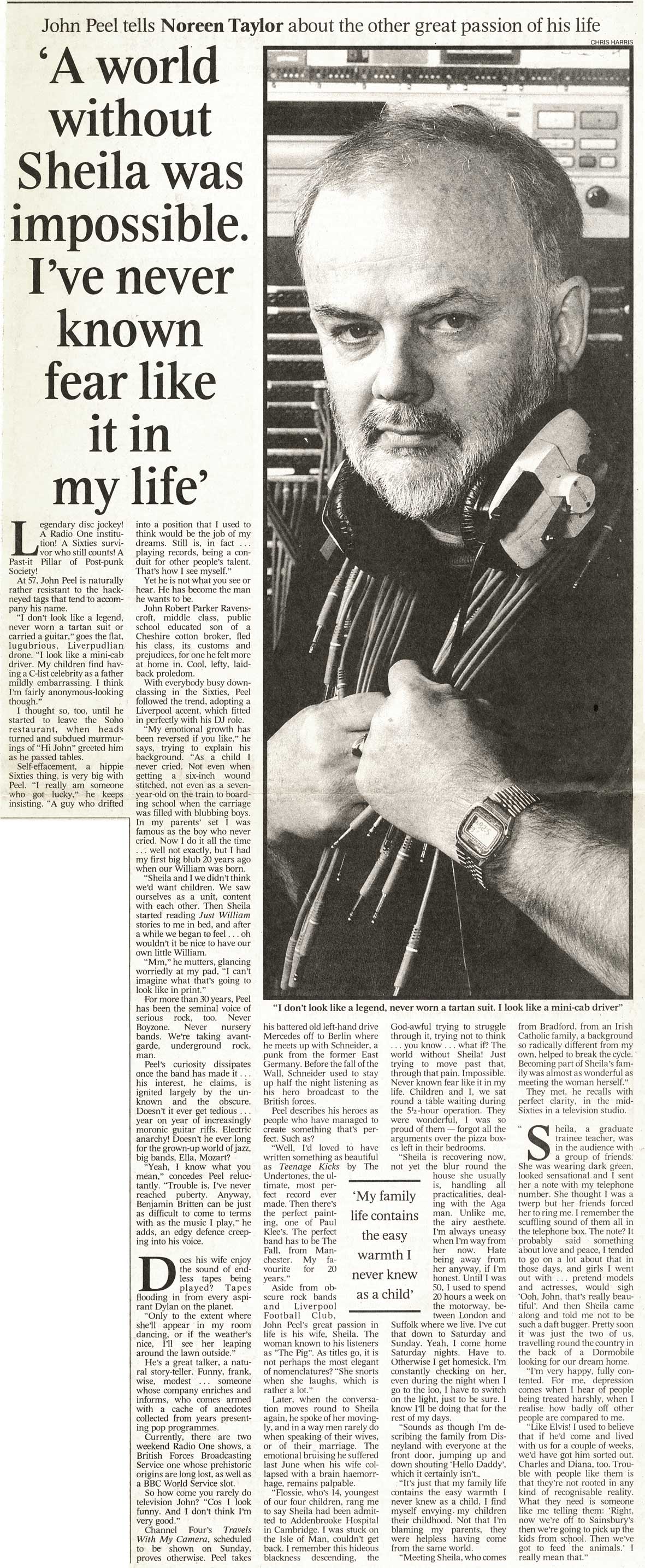

“1 don’t look like a legend, never worn a tartan suit or carried a guitar,” goes the flat, lugubrious, Liverpudlian drone. “I look like a mini-cab driver. My children find having a C-list celebrity as a father mildly embarrassing. 1 think I’m fairly anonymous-looking though.”

I thought so, too, until he started to leave the Soho restaurant, when heads turned and subdued murmurings of “Hi John” greeted him as he passed tables.

Self-effacement, a hippie Sixties thing, is very big with Peel. “I really am someone who got lucky,” he keeps insisting. “A guy who drifted into a position that I used to think would be the job of my dreams. Still is, in fact… playing records, being a conduit for other people’s talent. That’s how I see myself.”

Yet he is not what you see or hear. He has become the man he wants to be. John Robert Parker Ravenscroft, middle class, public school educated son of a Cheshire cotton broker, fled his class, its customs and prejudices, for one he felt more at home in. Cool, lefty, laid-back prole-dom. With everybody busy down-classing in the Sixties, Peel followed the trend, adopting a Liverpool accent, which fitted in perfectly with his DJ role.

“My emotional growth has been reversed if you like,” he says, trying to explain his background. “As a child I never cried. Not even when getting a six-inch wound stitched, not even as a seven-year-old on the train to boarding school when the carriage was filled with blubbing boys. In my parents’ set I was famous as the boy who never cried. Now I do it all the time… well not exactly, but I had my first big blub 20 years ago when our William was born.

“Sheila and I, we didn’t think we’d want children. We saw ourselves as a unit, content with each other. Then Sheila started reading Just Williamstories to me in bed, and after a while we began to feel… oh wouldn’t it be nice to have our own little William. “Mm,” he mutters, glancing worriedly at my pad, “I can’t imagine what that’s going to look like in print.”

For more than 30 years, Peel has been the seminal voice of serious rock, too. Never Boyzone. Never nursery bands. We’re talking avant-garde, underground rock, man. Peel’s curiosity dissipates once the band has made it… his interest, he claims, is ignited largely by the unknown and the obscure. Doesn’t it ever get tedious… year on year of increasingly moronic guitar riffs. Electric anarchy! Doesn’t he ever long for the grown-up world of jazz, big bands, Ella, Mozart?

“Yeah, I know what you mean,” concedes Peel reluctantly. “Trouble is, I’ve never reached puberty. Anyway, Benjamin Britten can be just as difficult to come to terms with as the music I play,” he adds, an edgy defence creeping into his voice.

Does his wife enjoy the sound of endless tapes being played? Tapes flooding in from every aspirant Dylan on the planet. “Only to the extent where she’ll appear in my room dancing, or if the weather’s nice. I’ll see her leaping around the lawn outside.”

He’s a great talker, a natural story-teller. Funny, frank, wise, modest… someone whose company enriches and informs, who comes armed with a cache of anecdotes collected from years presenting pop programmes.

Currently, there are two weekend Radio One shows, a British Forces Broadcasting Service, one whose prehistoric origins are long lost, as well as a BBC World Service slot. So how come you rarely do television John? “Cos I look funny. And I don’t think I’m very good.”

Currently, there are two weekend Radio One shows, a British Forces Broadcasting Service, one whose prehistoric origins are long lost, as well as a BBC World Service slot. So how come you rarely do television John? “Cos I look funny. And I don’t think I’m very good.”

Channel Four’s Travels With My Camera, scheduled to be shown on Sunday, proves otherwise. Peel takes his battered old left-hand drive Mercedes off to Berlin where he meets up with Schneider, a punk from the former East Germany. Before the fall of the Wall, Schneider used to stay up half the night listening as his hero broadcast to the British forces. Peel describes his heroes as people who have managed to create something that’s perfect. Such as?

“Well, I’d loved to have written something as beautiful as Teenage Kicks by The Undertones, the ultimate, most perfect record ever made. Then there’s the perfect painting, one of Paul Klee’s. The perfect band has to be The Fall, from Manchester. My favourite for 20 years.”

Aside from obscure rock bands and Liverpool Football Club, John Peel’s great passion in life is his wife, Sheila. The woman known to his listeners as “The Pig”. As titles go, it is not perhaps the most elegant of nomenclatures? “She snorts when she laughs, which is rather a lot.”

Later, when the conversation moves round to Sheila again, he spoke of her movingly, and in a way men rarely do when speaking of their wives, or of their marriage. The emotional bruising he suffered last June when his wife collapsed with a brain haemorrhage, remains palpable.

“Flossie, who’s 14, youngest of our four children, rang me to say Sheila had been admitted to Addenbrooke Hospital in Cambridge. I was stuck on the Isle of Man, couldn’t get back. I remember this hideous blackness descending, the God-awful trying to struggle through it, trying not to think… you know… what if? The world without Sheila! Just trying to move past that, through that pain. Impossible. Never known fear like it in my life.

“Children and I, we sat round a table waiting during the five-hour operation. They were wonderful, I was so proud of them — forgot all the arguments over the pizza boxes left in their bedrooms. Sheila is recovering now, not yet the blur round the house she usually is, handling all practicalities, dealing with the Aga man. Unlike me, the airy aesthete. I’m always uneasy when I’m way from her now. Hate being away from her anyway, if I’m honest.

“Until I was 50, I used to spend 20 hours a week on the motorway, between London and Suffolk where we live. I’ve cut that down to Saturday and Sunday. Yeah, I come home Saturday nights. Have to. Otherwise I get homesick. I’m constantly checking on her, even during the night when I go to the loo, I have to switch on the light, just to be sure. I know I’ll be doing that for the rest of my days.

“Sounds as though I’m describing the family from Disneyland with everyone at the front door, jumping up and down shouting ‘Hello Daddy’, which it certainly isn’t. It’s just that my family life contains the easy warmth I never knew as a child, I find myself envying my children their childhood. Not that I’m blaming my parents, they were helpless having come from the same world.

“Meeting Sheila, who comes from Bradford, from an Irish Catholic family, a background so radically different from my own, helped to break the cycle. Becoming part of Sheila’s family was almost as wonderful as meeting the woman herself.”

They met, he recalls with perfect clarity, in the mid-Sixties in a television studio. Sheila, a graduate trainee teacher, was in the audience with ‘ a group of friends: She was wearing dark green, looked sensational and I sent her a note with my telephone number.

She thought I was a twerp but her friends forced her to ring me. I remember the scuffling sound of them all in the telephone box. The note? It probably said something about love and peace. I tended to go on a lot about that in those days, and girls I went out with – pretend models and actresses – would sigh, ‘Ooh, John, that’s really beautiful’.

“And then Sheila came along and told me not to be such a daft bugger. Pretty soon it was just the two of us, travelling round the country in the back of a Dormobile looking for our dream home. I’m very happy, fully contented. For me, depression comes when I hear of people being treated harshly, when I realise how badly off other people are compared to me.

“Like Elvis! I used to believe that if he’d come and lived with us for a couple of weeks, we’d have got him sorted out. Charles and Diana, too. Trouble with people like them is that they’re not rooted in any kind of recognisable reality.

“What they need is someone like me telling them, ‘Right, now we’re off to Sainsbury’s then we’re going to pick up the kids from school. Then we’ve got to feed the animals.’ I really mean that.”