Emma Bridgewater | The Times | 12 August, 1998

Emma Bridgewater is to pottery what Laura Ashley was to summer dresses and Sybil Colefax was to chintz. The name symbolises not only a product but a lifestyle, conjuring up an image of the artless taste that exemplifies the continuing Arcadian romance of the English middle class.

Emma Bridgewater is to pottery what Laura Ashley was to summer dresses and Sybil Colefax was to chintz. The name symbolises not only a product but a lifestyle, conjuring up an image of the artless taste that exemplifies the continuing Arcadian romance of the English middle class.

Emma’s sponge-ware dinner sets are illustrated with faded roses and ferns. Her plates, jugs and cereal bowls are decorated with larky childish messages about good boys and girls. Chunky, unfussy, robust, it is both witty and practical, a vogueish must-have on the Welsh dressers of Annabels and Harrys from Wandsworth to Norfolk.

“When I look around me,” says Emma, standing in her shop in London’s Fulham Road, “I realise that what I’m doing is flogging the family silver, selling our secrets.”

It transpires that the great secret was in having a mother for whom work meant a talent for stylish living and a genius for decorating that eschewed any need to hire interior designers or to follow trends. It was her mother’s taste and her eye for a sort of cosy magic which, Emma insists, has enabled her to capitalise on nostalgia.

There is much poignancy when she mention the importance of her mother, a daughter of old country money. She was severely injured in a riding fall two years ago and has never recovered. The deep pain is etched on Emma’s face as she explains: “Since the accident my life has been in a spin. Certain values have changed. Not about work, though.

“The best thing I can say about myself is that I make jobs for 55 people in Stoke, that I’m proud of our pottery, of sustaining an industry in danger of disappearing like coal, steel and everything else the British once excelled at. Soon, nothing will be produced in this country. The countryside will be in danger of becoming one vast B&Q.”

This respect for manufacturing reminds her that it wasn’t only her mother’s sense of style that she absorbed. Her father made a fortune publishing educational books and she mastered his business acumen. With the dovetailing of those twin parental gifts, Emma was still in her twenties when, in the mid-1980s, she became one of the Thatcherite wunderkinder, a self-propelled success story.

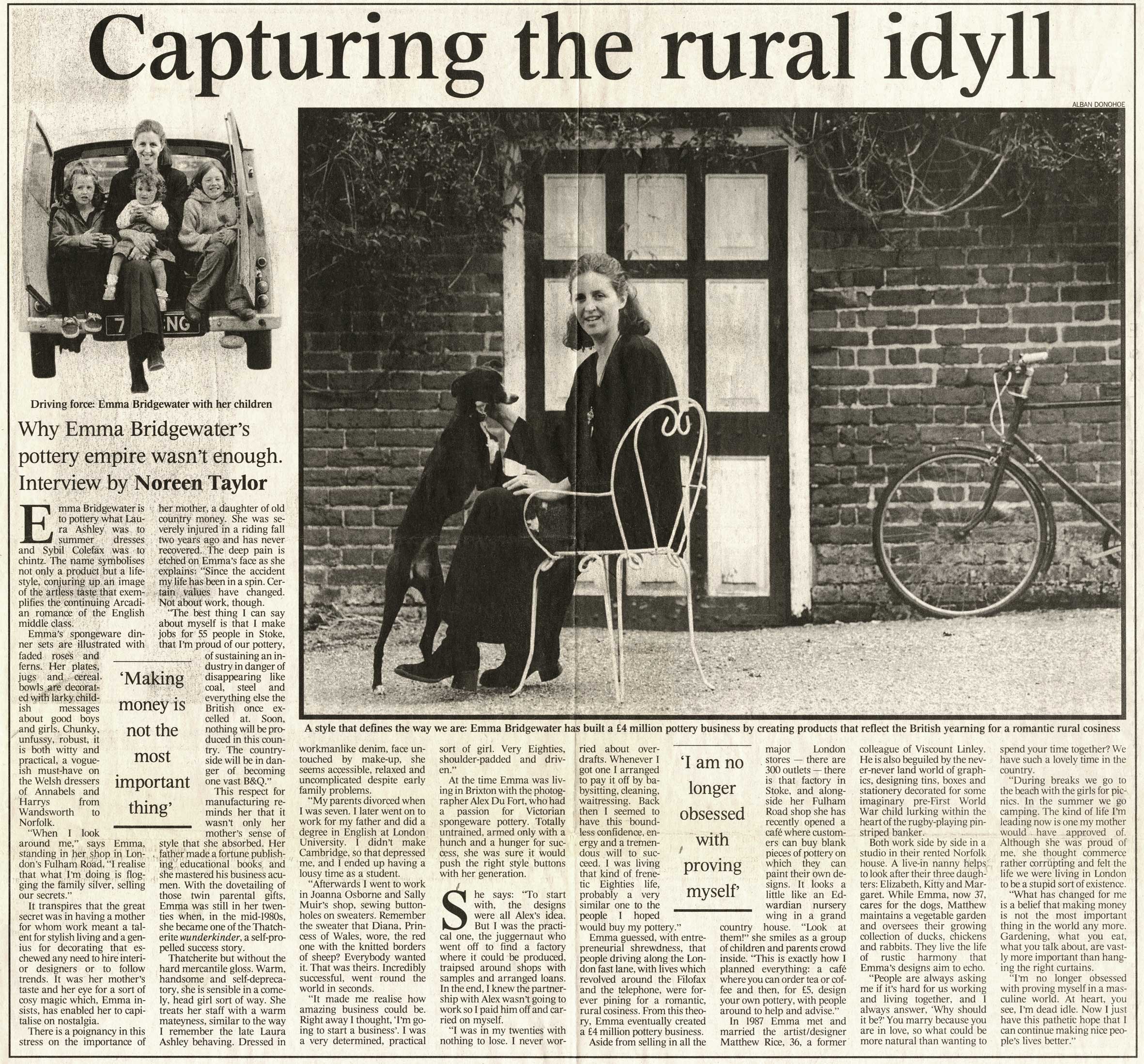

Thatcherite but without the hard, mercantile gloss. Warm, handsome and self-deprecatory, she is sensible in a comely, head girl sort of way. She treats her staff with a warm mateyness, similar to the way I remember the late Laura Ashley behaving. Dressed in workmanlike denim, face untouched by make-up, she seems accessible, relaxed and uncomplicated despite early family problems.

“My parents divorced when I was seven. I later went on to work for my father and did a degree in English at London University. I didn’t make Cambridge, so that depressed me, and I ended up having a lousy time as a student.

“Afterwards I went to work in Joanna Osborne and Sally Muir’s shop, sewing buttonholes on sweaters. Remember the sweater that Diana, Princess of Wales, wore, the red one with the knitted borders of sheep? Everybody wanted it. That was theirs. Incredibly successful, went around the world in seconds.

“It made me realise how amazing business could be. Right away I thought, I’m going to start a business’. I was a very determined, practical sort of girl. Very Eighties, shoulder-padded and driven.”

At the time Emma was living in Brixton with the photographer Alex Du Fort, who had a passion for Victorian spongeware pottery. Totally untrained, armed only with a hunch and a hunger for success, she was sure it would push the right style buttons with her generation.

She says: “To start with, the designs were all Alex’s idea. But I was the practical one, the juggernaut who went off to find a factory where it could be produced, traipsed around shops with samples and arranged loans. In the end, I knew the partnership with Alex wasn’t going to work so I paid him off and carried on myself.

“I was in my twenties with nothing to lose. I never worried about overdrafts. Whenever I got one I arranged to pay it off by babysitting, cleaning, waitressing. Back then I seemed to have this boundless confidence, energy and a tremendous will to succeed. I was living that kind of frenetic Eighties life, probably a very similar one to the people I hoped would buy my pottery.”

Emma guessed, with entrepreneurial shrewdness, that people driving along the London fast lane, with lives which revolved around the Filofax and the telephone, were forever pining for a romantic, rural cosiness. From this theory, Emma eventually created a Pounds 4 million pottery business.

Aside from selling in all the major London stores – there are 300 outlets – there is that factory in Stoke, and alongside her Fulham Road shop she has recently opened a cafe where customers can buy blank pieces of pottery on which they can paint their own designs. It looks a little like an Edwardian nursery wing in a grand country house. “Look at them!” she smiles as a group of children and parents crowd inside. “This is exactly how I planned everything: a cafe where you can order tea or coffee and then, for £5, design your own pottery, with people around to help and advice.”

In 1987 Emma met and married the artist/designer Matthew Rice, 36, a former colleague of Viscount Linley. He is also beguiled by the never-never land world of graphics, designing tins, boxes and stationery decorated for some imaginary pre-First World War child lurking within the heart of the rugby-playing pinstriped banker.

Both work side by side in a studio in their rented Norfolk house. A live-in nanny helps to look after their three daughters: Elizabeth, Kitty and Margaret. While Emma, now 37, cares for the dogs, Matthew maintains a vegetable garden and oversees their growing collection of ducks, chickens and rabbits. They live the life of rustic harmony that Emma’s designs aim to echo.

“People are always asking me if it’s hard for us working and living together, and I always answer : “Why should it be?’ You marry because you are in love, so what could be more natural than wanting to spend your time together? We have such a lovely time in the country.

“During breaks we go to the beach with the girls for picnics. In the summer we go camping. The kind of life I’m leading now is one my mother would have approved of. Although she was proud of me, she thought commerce rather corrupting and felt the life we were living in London to be a stupid sort of existence.

“What has changed for me is a belief that making money is not the most important thing in the world any more. Gardening, what you eat, what you talk about, are vastly more important than hanging the right curtains.

“I’m no longer obsessed with proving myself in a masculine world. At heart, you see, I’m dead idle. Now I just have this pathetic hope that I can continue making nice people’s lives better.”