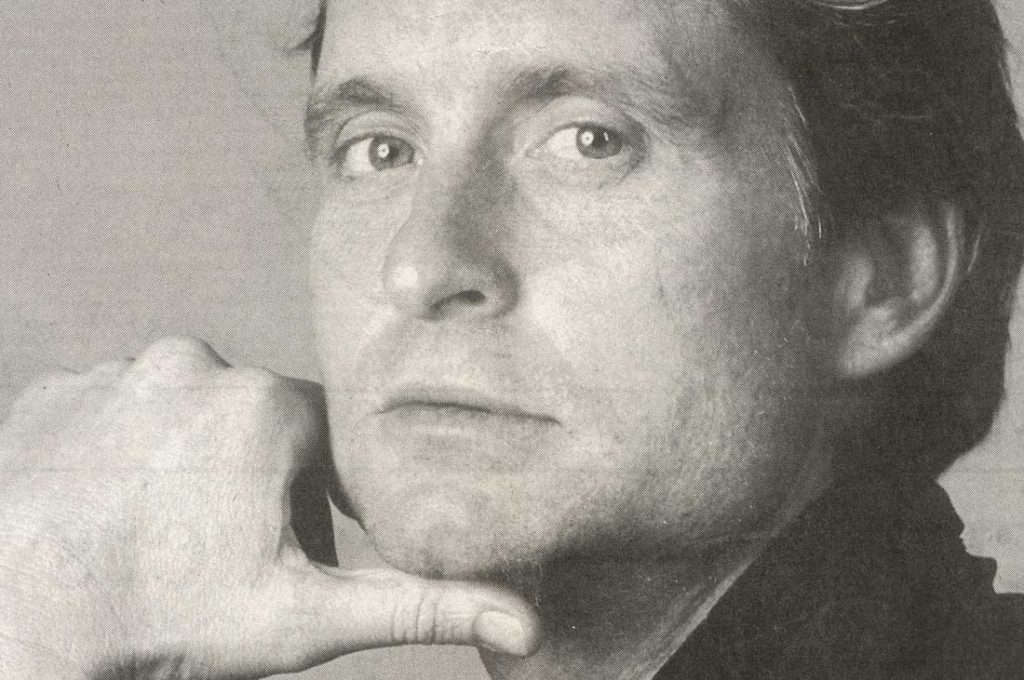

Michael Douglas | The Times | January 1997

Michael Douglas is intent on portraying a self that is as clear and direct as the steady, head-on gaze of his blue eyes. He is polite, self-assured in that American way that lends distance while allowing you to believe a warm candid encounter is on the agenda.

Michael Douglas is intent on portraying a self that is as clear and direct as the steady, head-on gaze of his blue eyes. He is polite, self-assured in that American way that lends distance while allowing you to believe a warm candid encounter is on the agenda.

“My brother, Joel, and a couple of buddies are out there now, exploring London,” he says, looking from a window in his Dorchester suite. “And in the usual vicarious way I’ll enjoy their adventures on their return.”

Douglas, one of the most successful actor-producers in Hollywood, has a film to promote, The Ghost and the Darkness, in which he stars with Val Kilmer. Constellation, his film company, rescued the William Goldman script which lay buried in a filing cabinet for six years.

It is a hugely enjoyable African romp complete with a pair of man-eating lions, achingly beautiful terrain, and the kind of heroic, hard-faced, safari-suited men last seen in Boy’s Ownannual strips. Doubtless Douglas would be happier if the film was all he had to worry about. Or talk about!

Instead, nightmarish beasts growl out scurrilous stories of self-destructive behaviour. The tabloid jungle drums tell tales of sex addiction, drug problems, alcoholism and the tortuous breakdown of his 19-year marriage to Diandra. Despite denials and claims of press fiction, he cannot cage the gossips. So he sits fidgeting, fingers entwined beneath his chin, dreading the moment when I inevitably will press him about his private life.

He is nice looking and well maintained, and the black polo neck jumper reveals the kind of flat stomach only a daily regime in the gym could produce in a man of 52. He thanks me for asking such an “interesting question”.

I had wanted to know where the incentive to succeed had come from. After all, his father, Kirk Douglas, the son of Russian immigrants who were dirt poor labourers, had dug his own track to stardom. Having reached the summit, he provided Douglas and his siblings with enough luxuries and riches to blunt even the most ravenous of appetites.

“True, my father was the kind of pioneer people write about. The one who had to struggle his way up from nothing, the great romantic rags to riches saga, that was him. Stories of how the sons of these famous fathers make it are not nearly so compelling, and it took a long time for me not to feel diminished by the accomplishments of a man who went to college on the back of a manure truck. Now it’s okay. We enjoy and are inspired by each other’s company.”

He has two Oscars, the first for producing One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nestin 1975, and the second as best actor in Wall Street.

Other films have earned either commercial and critical acclaim: China Syndrome, Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct, War of the Roses. Enough, surely, to have healed any competitive wounds as well as cementing his standing within the family.

“Oh sure, but it’s never that straightforward. My father has changed in that his values tend to be more spiritual now. Ten years ago, he survived a helicopter crash that killed two 19-year-old guys. Since then he’s been driven to find out why and for what purpose was he saved. He studies the Old Testament, has rediscovered his Judean roots. Being 80 years old makes you want to think about putting your house in order.

“Still hungry? My father? You bet, he wants to discuss movie projects with me and he’s writing his fifth novel.” His parents divorced when he was six and his mother, the British-born actress Diana Dill, remains, he says, “an active, inspirational woman for us all.”

Predictably, therapy-speak casts its fog over much of his conversation, obscuring meaning and providing formulaic responses when the going gets rough. So far, the impression he wants to project, perhaps for his own emotional wellbeing as much as the interview, is that his has been a blessed life, privileged, secure, with wonderful parents, punctuated by the thrills of success.

Why then, if this is the case, do people like him continue in a reckless search for the self-destructive highs that lead to detox clinics? He has also sought support from various AA groups. “What do you mean?” he asks. “What other highs?” The bottle kind. Booze. He asks: “Do you smoke?” Between five and ten a day.

“Right despite all the information you’ve accumulated, and despite the damage you know smoking wreaks on women, you still do it? Well there’s your answer. It’s the same with alcohol. Drinking has nothing to do with highs, thrills, whatever. It has to do with many other causes. Some of them inherited, as alcoholism is.

“Anyway, I’m not self-destructive. I’ve had my binges and excesses like most, and the reasons can range from needing to escape problems, like work pressures, marital issues and, like I said, it’s hereditary. Movie-making is an intensely creative process. You’re with this group of people 13 hours a day for weeks, then you break up and it’s like losing a family.

“But my God, when I read about my life and what I’m supposed to have got up to, I cringe. I hope nobody out there believes it. Like that sex-addiction stuff. Where does that come from? Yes, my lawyers are monitoring the situation, and I will sue if necessary.

“To start with it was funny, but now it’s hung around too long, and I find myself being repeatedly forced to discuss this nonsense with journalists who are supposed to be interested in my film work. Like this woman who wanted to interview me because she’d been through AA, and thought she’d be best placed to explain what I’d been through.

“Oh, and could I also explain to her what was behind my divorce. I wanted to say that I wouldn’t be saying ‘Hi’ to someone like her if it wasn’t for the film. What makes those tabloid guys think you’re going to spill out your life to a stranger anyway? As for divorce, Diandra and I are talking about separation. About taking a break, spending time apart. Ours remains a civilised relationship. We spent Christmas together in Africa.”

They met in 1977 at a Washington party for President Carter, when he was 33 and she was the 19-year-old daughter of a Spanish diplomat. Eight weeks later they married. They have one child: a 17-year-old son, Cameron, whose plans to become a disc jockey in London’s latest happening club have been shelved while he awaits sentencing on an incident that resulted in a crash near his home in Santa Barbara.

Nineteen years is a long time for a Hollywood marriage. “It’s a long time for any marriage,” he says, rocking back and forth, before embarking on one of those self-assuring mantras learnt in therapy.

“I believe in love and marriage and agree there’s nothing to beat coming home to a warm domestic setting. For the moment, however, I’m on my own, and that’s kind of exciting, too. Scary and exciting. It’s a new year, maybe a new life, and that’s good, too. Very positive. And I’m proud of the fact Diandra and I have a good dialogue.

“Dating new women? Oh, I wouldn’t even know how to get into all of that. Dating! What a strange concept,” he laughs. “Who knows what lies ahead, or who I’ll meet? Right now, I have no plans, aside from hanging out with my buddies. I know that love is not something you can plan on happening either.”

Still you never know who you’ll bump into on the golf course. “Very true, or on the ski slopes. The thought of growing old alone, that scares me. So, I don’t plan on it…”