Helen Mirren | The Times | September 1996

On the night before we met in Dublin, I had watched Helen Mirren skipping down the aisle in stockinged feet, shoes in one hand, the other held high in salute to the standing ovation greeting her as she strode on stage to take her bow at the premiere of Some Mother’s Son.

On the night before we met in Dublin, I had watched Helen Mirren skipping down the aisle in stockinged feet, shoes in one hand, the other held high in salute to the standing ovation greeting her as she strode on stage to take her bow at the premiere of Some Mother’s Son.

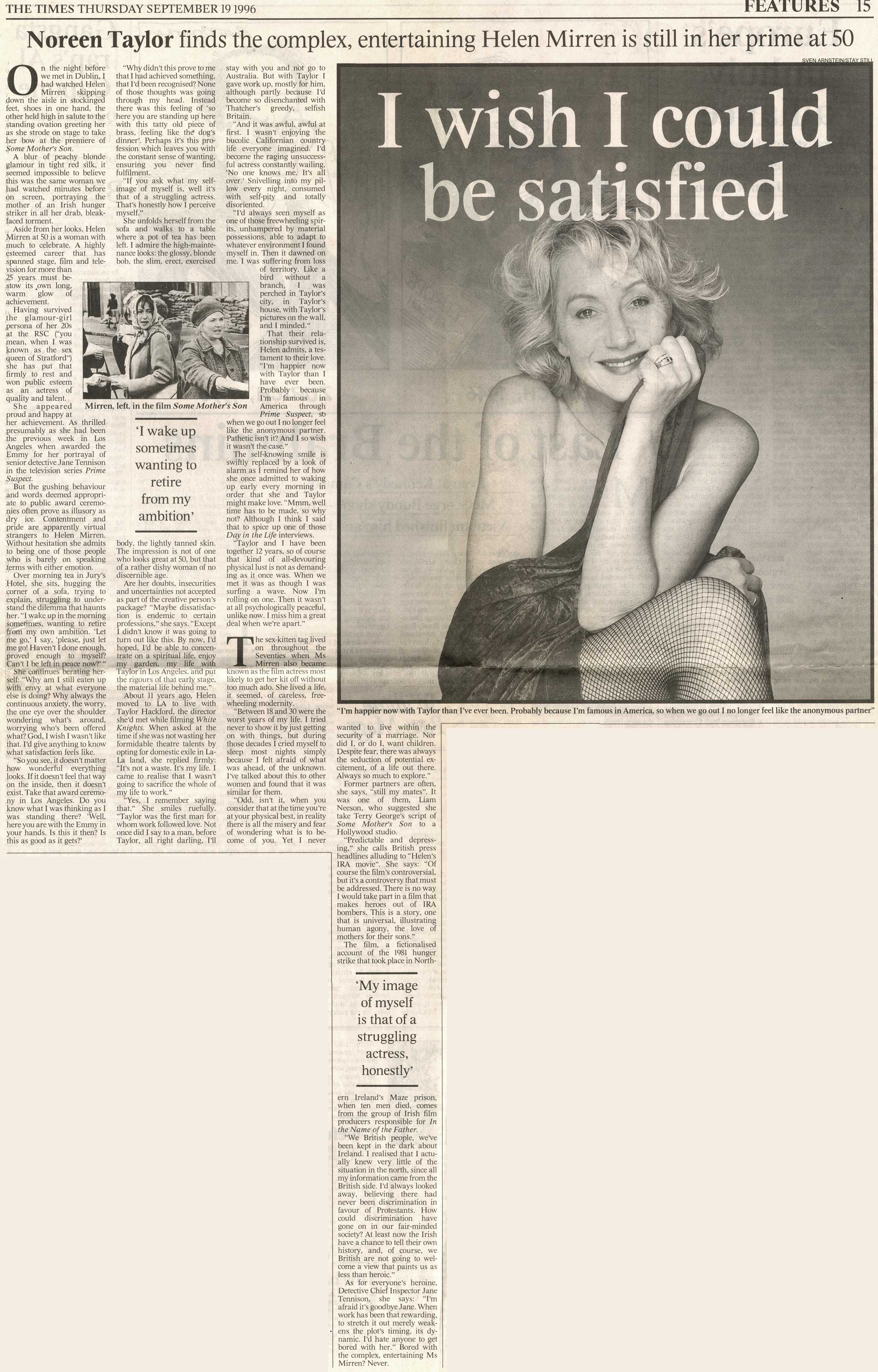

A blur of peachy blonde glamour in tight red silk, it seemed impossible to believe this was the same woman we had watched minutes before on screen, portraying the mother of an Irish hunger striker in all her drab, bleak-faced torment.

Aside from her looks, Helen Mirren at 50 is a woman with much to celebrate. A highly esteemed career that has spanned stage, film and television for more than 25 years must bestow its own long, warm glow of achievement.

Having survived the glamour-girl persona of her 20s at the RSC (“you mean, when I was known as the sex queen of Stratford”) she has put that firmly to rest and won public esteem as an actress of quality and talent. She appeared proud and happy at her achievement. As thrilled presumably as she had been the previous week in Los Angeles when awarded the Emmy for her portrayal of senior detective Jane Tennison in the television series Prime Suspect.

But the gushing behaviour and words deemed appropriate to public award ceremonies often prove as illusory as dry ice. Contentment and pride are apparently virtual strangers to Helen Mirren. Without hesitation she admits to being one of those people who is barely on speaking terms with either emotion.

Over morning tea in Jury’s Hotel, she sits, hugging the corner of a sofa, trying to explain, struggling to understand the dilemma that haunts her. “I wake up in the morning sometimes, wanting to retire from my own ambition. ‘Let me go,’ I say, ‘please, just let me go! Haven’t I done enough, proved enough to myself? Can’t I be left in peace now?’”

She continues berating herself: “Why am I still eaten up with envy at what everyone else is doing? Why always the continuous anxiety, the worry, the one eye over the shoulder wondering what’s around, worrying who’s been offered what? God, I wish I wasn’t like that. I’d give anything to know what satisfaction feels like.

“So, you see, it doesn’t matter how wonderful everything looks. If it doesn’t feel that way on the inside, then it doesn’t exist. Take that award ceremony in Los Angeles. Do you know what I was thinking as I was standing there? ‘Well, here you are with the Emmy in your hands. Is this it then? Is this as good as it gets?’

“Why didn’t this prove to me that I had achieved something, that I’d been recognised? None of those thoughts was going through my head. Instead there was this feeling of ‘so here you are standing up here with this tatty old piece of brass, feeling like the dog’s dinner.’ Perhaps it’s this profession which leaves you with the constant sense of wanting, ensuring you never find fulfilment

“If you ask what my self-image is, well it’s that of a struggling actress. That’s honestly how I perceive myself.” She unfolds herself from the sofa and walks to a table where a pot of tea has been left. I admire the high-maintenance looks: the glossy, blonde bob, the slim, erect, exercised body, the lightly tanned skin.

The impression is not of one who looks great at 50, but that of a rather dishy woman of no discernible age. Are her doubts, insecurities and uncertainties not accepted as part of the creative person’s package?

“Maybe dissatisfaction is endemic to certain professions,” she says. “Except I didn’t know it was going to turn out like this. By now, I’d hoped. I’d be able to concentrate on a spiritual life, enjoy my garden, my life with Taylor in Los Angeles, and put the rigours of that early stage, the material life behind me.”

About 11 years ago, Helen moved to LA to live with Taylor Hackford, the director she’d met while filming White Knights. When asked at the time if she was not wasting her formidable theatre talents by opting for domestic exile in La La Land, she replied firmly: “It’s not a waste. It’s my life. I came to realise that I wasn’t going to sacrifice the whole of my life to work.”

“Yes, I remember saying that.” She smiles ruefully. “Taylor was the first man for whom work followed love. Not once did I say to a man, before Taylor, all right darling. I’ll stay with you and not go to Australia. But with Taylor I gave work up, mostly for him, although partly because I’d become so disenchanted with Thatcher’s greedy, selfish Britain.

“And it was awful, awful at first. I wasn’t enjoying the bucolic Californian country life everyone imagined. I’d become the raging unsuccessful actress constantly wailing, ‘No one knows me. It’s all over.’ Snivelling into my pillow every night, consumed with self-pity and totally disoriented. I’d always seen myself as one of those freewheeling spirits, unhampered by material possessions, able to adapt to whatever environment I found myself in.

“Then it dawned on me. I was suffering from loss of territory. Like a bird without a branch, I was perched in Taylor’s city, in Taylor’s house, with Taylor’s pictures on the wall, and I minded.” That their relationship survived is, Helen admits, a testament to their love.

“I’m happier now with Taylor than I have ever been. Probably because I’m famous in America through Prime Suspect, so when we go out I no longer feel like the anonymous partner. Pathetic isn’t it? And I so wish it wasn’t the case.”

The self-knowing smile is swiftly replaced by a look of alarm as I remind her of how she once admitted to waking up early every morning in order that she and Taylor might make love. “Mmm, well time has to be made, so why not? Although I think I said that to spice up one of those Day in the Life interviews.

“Taylor and I have been together 12 years, so of course that kind of all-devouring physical lust is not as demanding as it once was. When we met it was as though I was surfing a wave. Now I’m rolling on one. Then it wasn’t at all psychologically peaceful, unlike now. I miss him a great deal when we’re apart.”

The sex-kitten tag lived on throughout the Seventies when Ms Mirren also became known as the film actress most likely to get her kit off without too much ado. She lived a life, it seemed, of careless, free-wheeling modernity.

“Between 18 and 30 were the worst years of my life. I tried never to show it by just getting on with things, but during those decades I cried myself to sleep most nights simply because I felt afraid of what was ahead, of the unknown.

“I’ve talked about this to other women and found that it was similar for them. Odd, isn’t it, when you consider that at the time you’re at your physical best, in reality there is all the misery and fear of wondering what is to become of you. Yet I never wanted to live within the security of a marriage. Nor did I, or do I, want children. Despite fear, there was always the seduction of potential excitement, of a life out there. Always so much to explore.” Former partners are often, she says, “still my mates.”

It was one of them, Liam Neeson, who suggested she take Terry George’s script of Some Mother’s Sonto a Hollywood studio.

“Predictable and depressing,” she calls British press headlines alluding to “Helen’s IRA movie”. She says: “Of course the film’s controversial, but it’s a controversy that must be addressed.

“There is no way I would take part in a film that makes heroes out of IRA bombers. This is a story, one that is universal, illustrating human agony, the love of mothers for their sons.” The film, a fictionalised account of the 1981 hunger strike that took place in Ireland’s Maze prison, when ten men died, comes from the group of Irish film producers responsible for In the Name of theFather.

“We British people, we’ve been kept in the dark about Ireland. I realised that I actually knew very little of the situation in the north, since all my information came from the British side. I’d always looked away, believing there had never been discrimination in favour of Protestants.

“How could discrimination have gone on in our fair-minded society? At least now the Irish have a chance to tell their own history, and, of course, we British are not going to welcome a view that paints us as less than heroic.”

As for everyone’s heroine, Detective Chief Inspector Jane Tennison, she says: “I’m afraid it’s goodbye Jane. When work has been that rewarding, to stretch it out merely weakens the plot’s timing, its dynamic. I’d hate anyone to get bored with her.” Bored with the complex, entertaining Ms Mirren? Never.