Ines de la Fressange | The Times | March 1998

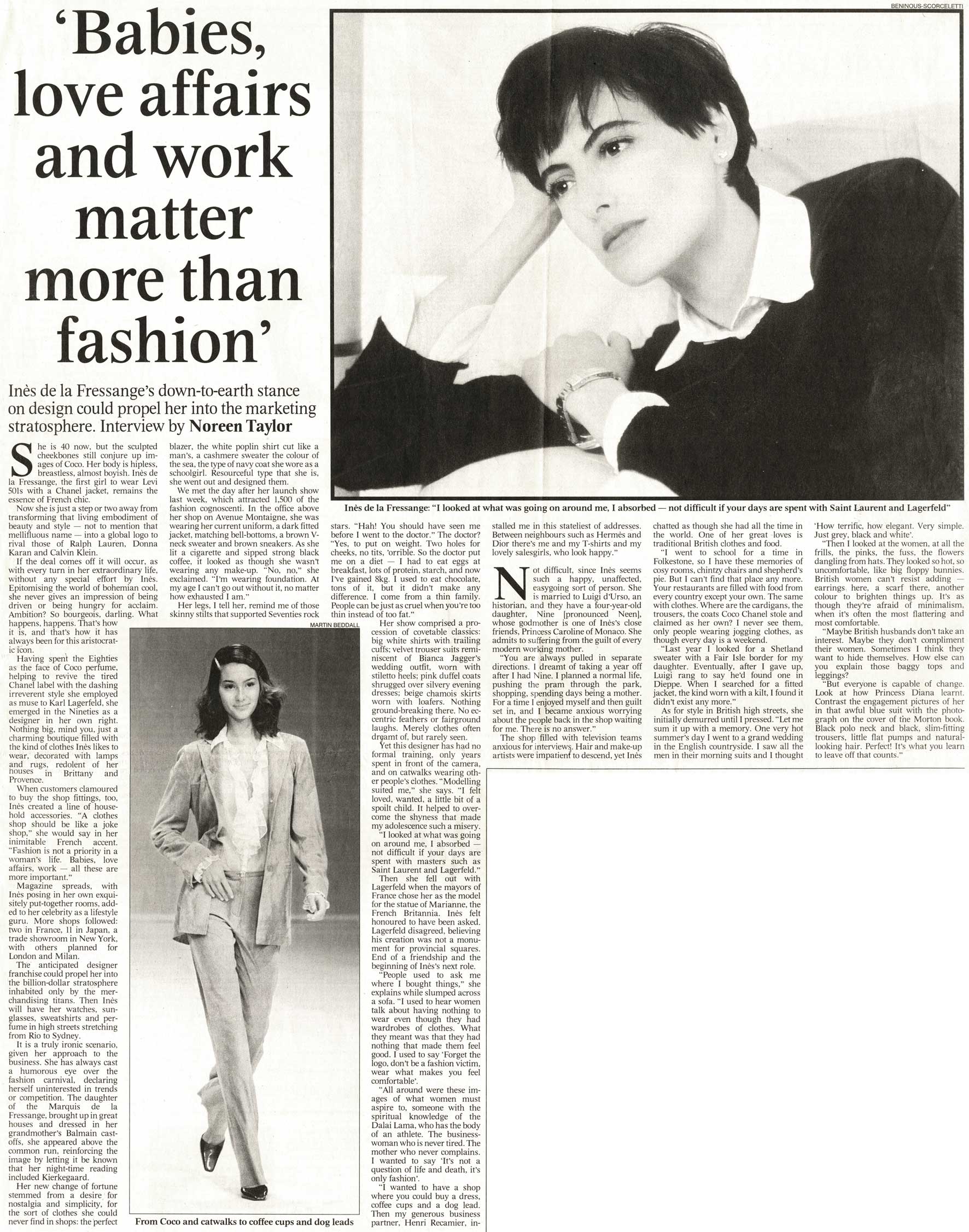

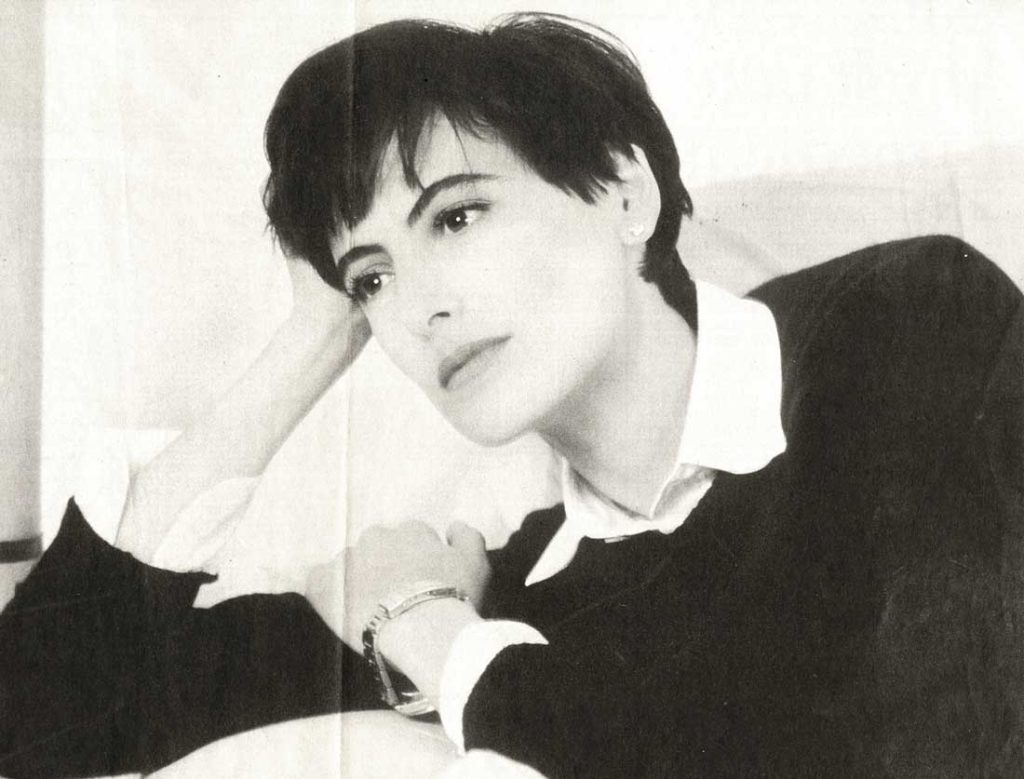

Zaneet Aman She is 40 now, but the sculpted cheekbones still conjure up images of Coco. Her body is hipless, breastless, almost boyish. Ines de la Fressange, the first girl to wear Levi 501s with a Chanel jacket, remains the essence of French chic.

Zaneet Aman She is 40 now, but the sculpted cheekbones still conjure up images of Coco. Her body is hipless, breastless, almost boyish. Ines de la Fressange, the first girl to wear Levi 501s with a Chanel jacket, remains the essence of French chic.

Now she is just a step or two away from transforming that living embodiment of beauty and style – not to mention that mellifluous name – into a global logo to rival those of Ralph Lauren, Donna Karan and Calvin Klein.

If the deal comes off it will occur, as with every turn in her extraordinary life, without any special effort by Ines. Epitomising the world of bohemian cool, she never gives an impression of being driven or being hungry for acclaim. Ambition? So bourgeois, darling. What happens, happens.

That’s how it is, and that’s how it has always been for this aristocratic icon. Having spent the Eighties as the face of Coco perfume, helping to revive the tired Chanel label with the dashing irreverent style she employed as muse to Karl Lagerfeld, she emerged in the Nineties as a designer in her own right. Nothing big, mind you, just a charming boutique filled with the kind of clothes Ines likes to wear, decorated with lamps and rugs, redolent of her houses in Brittany and Provence.

When customers clamoured to buy the shop fittings, too, Ines created a line of household accessories. “A clothes shop should be like a joke shop,” she would say in her inimitable French accent. “Fashion is not a priority in a woman’s life. Babies, love affairs, work – all these are more important.”

Magazine spreads, with Ines posing in her own exquisitely put-together rooms, added to her celebrity as a lifestyle guru. More shops followed: two in France, 11 in Japan, a trade showroom in New York, with others planned for London and Milan. The anticipated designer franchise could propel her into the billion-dollar stratosphere inhabited only by the merchandising titans.

Then Ines will have her watches, sunglasses, sweatshirts and perfume in high streets stretching from Rio to Sydney. It is a truly ironic scenario, given her approach to the business. She has always cast a humorous eye over the fashion carnival, declaring herself uninterested in trends or competition.

The daughter of the Marquis de la Fressange, brought up in great houses and dressed in her grandmother’s Balmain cast-offs, she appeared above the common run, reinforcing the image by letting it be known that her night-time reading included Kierkegaard.

Her new change of fortune stemmed from a desire for nostalgia and simplicity, for the sort of clothes she could never find in shops: the perfect blazer, the white poplin shirt cut like a man’s, a cashmere sweater the colour of the sea, the type of navy coat she wore as a schoolgirl. Resourceful type that she is, she went out and designed them.

We met the day after her launch show last week, which attracted 1,500 of the fashion cognoscenti. In the office above her shop on Avenue Montaigne, she was wearing her current uniform, a dark fitted jacket, matching bell-bottoms, a brown V-neck sweater and brown sneakers. As she lit a cigarette and sipped strong black coffee, it looked as though she wasn’t wearing any make-up.

“No, no,” she exclaimed. “I’m wearing foundation. At my age I can’t go out without it, no matter how exhausted I am.” Her legs, I tell her, remind me of those skinny stilts that supported Seventies rock stars. “Hah! You should have seen me before I went to the doctor.” The doctor?

“Yes, to put on weight. Two holes for cheeks, no tits, ’orrible. So the doctor put me on a diet – I had to eat eggs at breakfast, lots of protein, starch, and now I’ve gained 8kg. I used to eat chocolate, tons of it, but it didn’t make any difference. I come from a thin family. People can be just as cruel when you’re too thin instead of too fat.”

Her show comprised a procession of covetable classics: big white shirts with trailing cuffs; velvet trouser suits reminiscent of Bianca Jagger’s wedding outfit, worn with stiletto heels; pink duffel coats shrugged over silvery evening dresses; beige chamois skirts worn with loafers. Nothing ground-breaking there. No eccentric feathers or fairground laughs. Merely clothes often dreamt of, but rarely seen.

Yet this designer has had no formal training, only years spent in front of the camera, and on catwalks wearing other people’s clothes. “Modelling suited me,” she says. “I felt loved, wanted, a little bit of a spoilt child. It helped to overcome the shyness that made my adolescence such a misery. I looked at what was going on around me, I absorbed – not difficult if your days are spent with masters such as Saint Laurent and Lagerfeld.”

Then she fell out with Lagerfeld when the mayors of France chose her as the model for the statue of Marianne, the French Britannia. Ines felt honoured to have been asked. Lagerfeld disagreed, believing his creation was not a monument for provincial squares. End of a friendship and the beginning of Ines’s next role.

“People used to ask me where I bought things,” she explains while slumped across a sofa. “I used to hear women talk about having nothing to wear even though they had wardrobes of clothes. What they meant was that they had nothing that made them feel good. I used to say, ‘Forget the logo, don’t be a fashion victim, wear what makes you feel comfortable’.

“All around were these images of what women must aspire to, someone with the spiritual knowledge of the Dalai Lama, who has the body of an athlete. The businesswoman who is never tired. The mother who never complains. I wanted to say, ‘It’s not a question of life and death, it’s only fashion’.

“I wanted to have a shop where you could buy a dress, coffee cups and a dog lead. Then my generous business partner, Henri Recamier, installed me in this stateliest of addresses. Between neighbours such as Hermes and Dior there’s me and my T-shirts and my lovely salesgirls, who look happy.”

Not difficult, since Ines seems such a happy, unaffected, easy-going sort of person. She is married to Luigi d’Urso, an historian, and they have a four-year-old daughter, Nine [pronounced Neen|, whose godmother is one of Ines’s close friends, Princess Caroline of Monaco. She admits to suffering from the guilt of every modern working mother.

“You are always pulled in separate directions. 1 dreamt of taking a year off after I had Nine. I planned a normal life, pushing the pram through the park, shopping, spending days being a mother. For a time, I enjoyed myself and then guilt set in, and I became anxious worrying about the people back in the shop waiting for me. There is no answer.”

The shop filled with television teams anxious for interviews. Hair and make-up artists were impatient to descend, yet Ines chatted on as though she had all the time in the world. One of her great loves is traditional British clothes and food.

“I went to school for a time in Folkestone, so I have these memories of cosy rooms, chintzy chairs and shepherd’s pie. But I can’t find that place any more. Your restaurants are filled with food from every country except your own. The same with clothes. Where are the cardigans, the trousers, the coats Coco Chanel stole and claimed as her own? I never see them, only people wearing jogging clothes, as though every day is a weekend.

“Last year I looked for a Shetland sweater with a Fair Isle border for my daughter. Eventually, after I gave up, Luigi rang to say he’d found one in Dieppe. When I searched for a fitted jacket, the kind worn with a kilt, I found it didn’t exist anymore.”

As for style in British high streets, she initially demurred until I pressed. “Let me sum it up with a memory. One very hot summer’s day I went to a grand wedding in the English countryside. I saw all the men in their morning suits and I thought ‘how terrific, how elegant. Very simple. Just grey, black and white.’

“Then I looked at the women, at all the frills, the pinks, the fuss, the flowers dangling from hats. They looked so hot, so uncomfortable, like big floppy bunnies. British women can’t resist adding – earrings here, a scarf there, another colour to brighten things up. It’s as though they’re afraid of minimalism, when it’s often the most flattering and most comfortable.

“Maybe British husbands don’t take an interest. Maybe they don’t compliment their women. Sometimes I think they want to hide themselves. How else can you explain those baggy tops and leggings?

“But everyone is capable of change. Look at how Princess Diana learnt. Contrast the engagement pictures of her in that awful blue suit with the photograph on the cover of the Morton book. Black polo neck and black, slim-fitting trousers, little flat pumps and natural looking hair. Perfect! It’s what you learn to leave off that counts.”