Michael Flatley | The Times | December 1998

It is a scene that the fans of Michael Flatley, the flamboyant dancer, never see and one his detractors could never imagine. “Before the curtain goes up at each concert I kneeldown on stage and offer up heartfelt thanks to God for helping me to carry through my dream, for rescuing me from a life of labouring in the freezing cold,” he says.

It is a scene that the fans of Michael Flatley, the flamboyant dancer, never see and one his detractors could never imagine. “Before the curtain goes up at each concert I kneeldown on stage and offer up heartfelt thanks to God for helping me to carry through my dream, for rescuing me from a life of labouring in the freezing cold,” he says.

He is referring to the years, not so long ago, when he wore boots more often than tap shoes. “Not that I’m ashamed of digging ditches. Any man who does that kind of work can hold his head up. I’m proud. I earned a living and I kept my body fit.”

The sincerity is obvious, evidence of theparadox between Flatley theman andFlatleytheshowman. Up close, in private, he is unpretentious, earnest and engaging. He is also very smart. But his public image, not to mention his reputation, is of a narcissistic prima donna, a star unable to deal with sudden global fame.

There was the acrimonious split with his original Riverdancepartner and recently, a court battle with his former manager attractingpublicity Flatley could have done without.

Perhaps the misrepresentation begins with his clothes and appearance. When we meet he is wearing a black leather coat, black shirt, black trousers and black Cuban-heeled boots. His December tan is offset by a headlight sized diamond dazzling from his left ear. As soon as we begin to talk this ostentatious veneer loses its significance.

Flatley, who literally leapt to fame in Riverdanceand has gone on to make millions as the creator, choreographer, producer and star of Lord of the Danceextravaganza, is not in the least conceited.

Admittedly, we do share a love for traditional Irish dancing, which was unknown outside Ireland and its expatriate communities in our youth.

We swap childhood stories about nights spent in draughty halls practising hard reels and slip jigs, training the feet to land in the correct position after a leap, as anxious parents looked on, travelling to compete in feises(festivals). He was not at all enthusiastic about dancing when, aged 11, his mother, Eilish, took him and his four siblings to dance classes in one of Chicago’s Irish community church halls.

“I hated every minute. I had to be pulled there by the ears practically. Baseball, skating, boxing; all took priority over Irish dancing. In fact, my father insisted my brother and I had boxing lessons so we could protect ourselves from other boys attacking us because we went to dance classes.”

Flatley was born in 1958, in Chicago’s tough South Side, after his parents emigrated from Co Carlow, though he spent much of his childhood going back and forth to Ireland to stay with his late grandmother, a former Irish dance champion. In a voice that softly blends Irish and American accents he says:

“My grandmother was the great influence in my life; she swore you could get everything you wanted if you concentrated and worked hard. I remember her walking round her own fields, describing to me the importance of land and her love of it, and how she couldn’t bear to leave it, even for a holiday in America. I keep a seat empty for her at all my concerts.”

Despite his initial reluctance, dancing eventually became his passion.

“I fell in love with it, and with the music. I learnt to play the flute. To this day it still makes me happier than anything else.”

At 17, he won the World Dance Championship in Dublin, but was unsure what he should do. “All I knew was that I had this obsession, but this was long before Irish music and dancing became recognised, so how could 1 earn my living as an Irish dancer?”

His first break came in meeting The Chieftains, the only band then playing traditional music on the international stage, and they invited him to tour with them. “For the first time I had freedom to express what I felt. The Chieftains encouraged me to create different dances and steps, so I began dancing with my hands on my hips instead of the traditional style, where they’re held firmly at the sides.”

But the ten years of tours, in which he played flute and danced, were neither long enough nor lucrative enough for him to support himself. Hence the days as a ditch-digger. He was finally able to lay down his shovel in 1994, when he was asked to take the lead role in a seven-minute interval entertainment at the Eurovision Song Contest in Dublin.

Riverdance, conceived by the producer Moya Doherty, was a spell-binding experience that captivated global television audiences who didn’t know a reel from a rumba. Overnight, Irish dance was transformed into a mass-market phenomenon and a two-hour show was soon playing to packed audiences.

Flatley was Riverdance’s chief choreographer and dancer but left a year later after disagreements with Doherty. She believed the essence of the show lay in its collective vitality. Flatley needed to be a soloist, a controller, the main man.

So, within eight weeks, he created his own showcase, Lord of the Dance. Since then he has made millions from a series of international sell-out concerts. His last video broke American records as the biggest-selling performance video to date. He has a troupe based in Paris, another is planned for London, while a third will tour the world.

Meanwhile, the virtuoso Flatley dances on, defying his age. Irish dancing demands such high levels of stamina that it is unusual for anyone to perform much beyond their twenties.

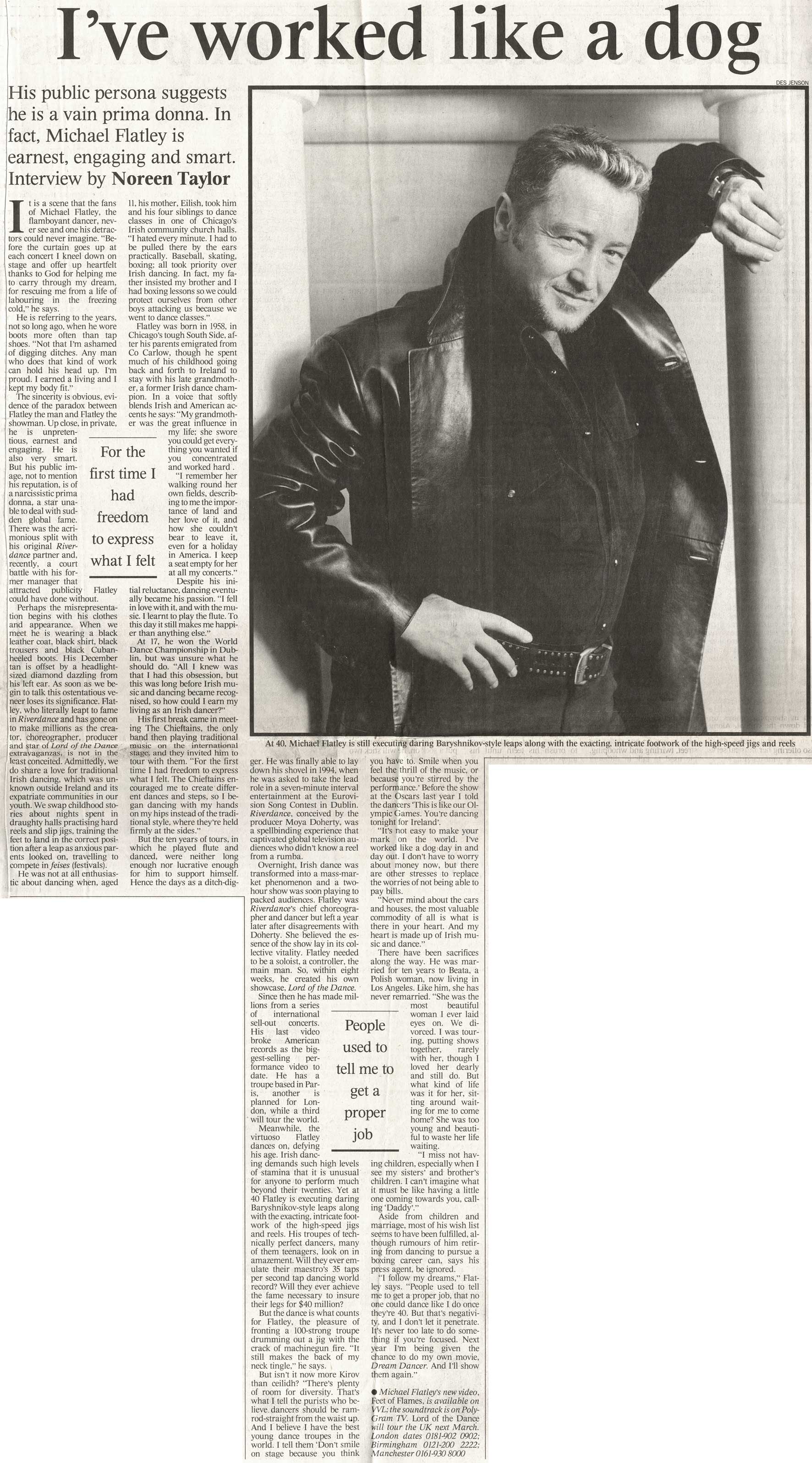

Yet at 40, Flatley is executing daring Baryshnikov-style leaps along with the exacting, intricate footwork of the high-speed jigs and reels. His troupes of technically perfect dancers, many of them teenagers, look on in amazement. Will they ever emulate their maestro’s 35 taps per second tap dancing world record? Will they ever achieve the fame necessary to insure their legs for $40 million?

But the dance is what counts for Flatley, the pleasure of fronting a 100-strong troupe drumming out a jig with the crack of machine gun fire. “It still makes the back of my neck tingle,” he says.

But isn’t it now more Kirov than ceilidh? “There’s plenty of room for diversity. That’s what I tell the purists who believe dancers should be ramrod-straight from the waist up. And I believe I have the best young dance troupes in the world.

I tell them, ‘Don’t smile on stage because you think you have to. Smile when you feel the thrill of the music, or because you’re stirred by the performance.’ Before the show at the Oscars last year I told the dancers, ‘This is like our Olympic Games. You’re dancing tonight for Ireland’.

“It’s not easy to make your mark on the world. I worked like a dog day in and day out. 1 don’t have to worry about money now, but there are other stresses to replace the worries of not being able to pay bills. Never mind about the cars and houses, the most valuable commodity of all is what is there in your heart. And my heart is made up of Irish music and dance.”

There have been sacrifices along the way. He was married for ten years to Beata, a Polish woman, now living in Los Angeles. Like him, she has never remarried.

“She was the most beautiful woman I ever laid eyes on. We divorced. I was touring, putting shows together, rarely with her, though 1 loved her dearly and still do. What kind of life was it for her, sitting around waiting for me to come home?

“She was too young and beautiful to waste her life waiting. I miss not having children, especially when I see my sisters’ and brother’s children. I can’t imagine what it must be like having a little one coming towards you, calling ‘Daddy’”.

Aside from children and marriage, most of his wish list seems to have been fulfilled, although rumours of him retiring from dancing to pursue a boxing career can, says his press agent, be ignored. “I follow my dreams,” Flatley says. “People used to tell me to get a proper job, that no one could dance like I do once they’re 40. But that’s negativity, and I don’t let it penetrate.

“It’s never too late to do something if you’re focused. Next year I’m being given the chance to do my own movie, Dream Dancer. And I’ll show them again.”