Mike Tyson | The Daily Mirror | February 1992

This was following his conviction for rape, a month later he was sentenced to six years in prison.

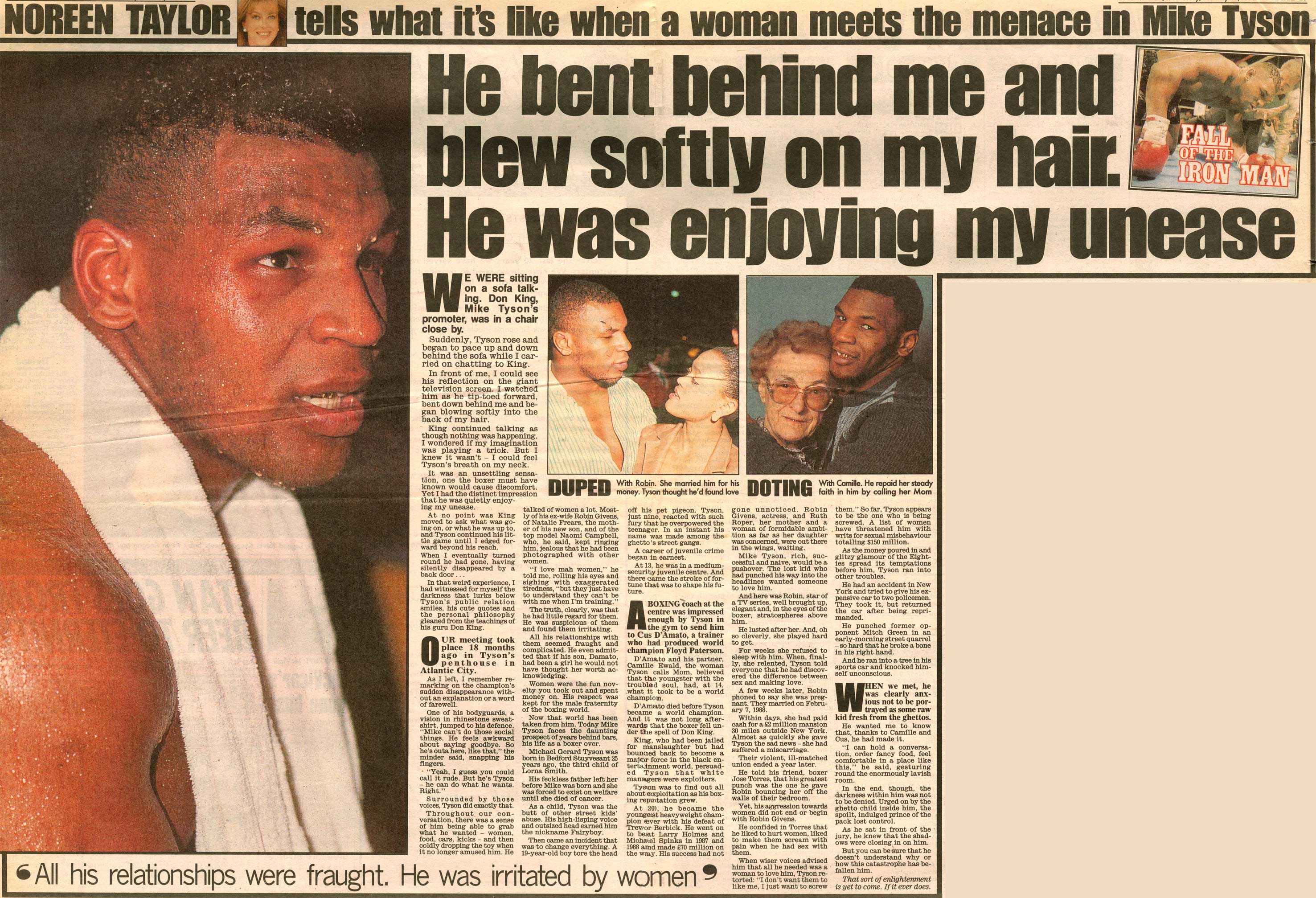

We were sitting on a sofa talking. Don King, Mike Tyson’s promoter, was in a chair close by. Suddenly, Tyson rose and began to pace up and down behind the sofa while I carried on chatting to King.

We were sitting on a sofa talking. Don King, Mike Tyson’s promoter, was in a chair close by. Suddenly, Tyson rose and began to pace up and down behind the sofa while I carried on chatting to King.

In front of me, I could see his reflection on the giant television screen. I watched him as he tiptoed forward, bent down behind me and began blowing softly into the back of my hair.

King continued talking as though nothing was happening. I wondered if my imagination was playing a trick. But I knew it wasn’t – I could feel Tyson’s breath on my neck.

It was an unsettling sensation, one the boxer must have known would cause discomfort. Yet I had the distinct impression that he was quietly enjoying my unease.

At no point was King moved to ask what was going on, or what he was up to and Tyson continued his little game until I edged forward

beyond his reach. When I eventually turned round he had gone, having silently disappeared by a back door…

In that weird experience, I had witnessed for myself the darkness that lurks below Tyson’s public relation smiles, his cute quotes and the personal philosophy gleaned from the teachings of his guru, Don King.

Our meeting took place 18 months ago in Tyson’s penthouse in Atlantic City. As I left. I remember remarking on the champion’s sudden disappearance without an explanation or a word of farewell.

One of his bodyguards, a vision in rhinestone sweatshirt, jumped to his defence. “Mike can’t do those social things. He feels awkward about saying goodbye. So he’s outta here, like that,” the minder said, snapping his fingers.

“Yeah. I guess you could call It rude. But he’s Tyson – he can do what he wants. Right.” Surrounded by those voices, Tyson did exactly that.

Throughout our conversation, there was a sense of him being able to grab what he wanted – women, food, cars, kicks – and then coldly dropping the toy when it no longer amused him.

He talked of women a lot. Mostly of his ex-wife, Robin Givens, of Natalie Frears, the mother of his new son, and of the top model Naomi Campbell, who, he said, kept ringing him, jealous that he had been photographed with other women.

“I love mah women,” he told me, rolling his eyes and sighing with exaggerated tiredness, “but they just have to understand they can’t be with me when I’m training.” The truth, clearly, was that he had little regard for them. He was suspicious of them and found them irritating.

All his relationships with them seemed fraught and complicated. He even admitted that if his son, Damato, had been a girl he would not have thought her worth acknowledging. Women were the fun novelty you took out and spent money on. His respect was kept for the male fraternity of the boxing world.

Now that world has been taken from him. Today Mike Tyson faces the daunting prospect of years behind bars, his life as a boxer over.

Michael Gerard Tyson was born in Bedford Stuyvesant 25 years ago, the third child of Lorna Smith. His feckless father left her before Mike was born and she was forced to exist on welfare until she died of cancer.

As a child, Tyson was the butt of other street kids’ abuse. His high-lisping voice and outsized head earned him the nickname Fairyboy. Then came an incident that was to change everything. A 19-year-old boy tore the head off his pet pigeon.

Tyson, just nine, reacted with such fury that he overpowered the teenager. In an instant his name was made among the ghetto’s street gangs. A career of Juvenile crime began in earnest. At 13, he was In a medium security juvenile centre. And there came the stroke of fortune that was to shape his future.

A boxing coach at the centre was impressed enough by Tyson in the gym to send him to Cus D’Amato, a trainer who had produced world champion Floyd Paterson. D’Amato and his partner, Camille Ewald. the woman Tyson calls Mom, believed that the youngster with the troubled soul, had, at 14, what it took to be a world champion.

D’Amato died before Tyson became a world champion. And it was not long afterwards that the boxer fell under the spell of Don King.

King, who had been jailed for manslaughter but had bounced back to become a major force in the black entertainment world, persuaded Tyson that white managers were exploiters. Tyson was to find out all about exploitation as his boxing reputation grew.

At 20, he became the youngest heavyweight champion ever with his defeat of Trevor Berbick. He went on to beat Larry Holmes and Michael Spinks in 1967 and 1968 and made £70 million on the way.

His success had not gone unnoticed. Robin Givens, actress, and Ruth Roper, her mother, and a woman of formidable ambition as far as her daughter was concerned, were out there in the wings, waiting.

Mike Tyson, rich, successful and naïve, would be a pushover. The lost kid who had punched his way into the headlines wanted someone to love him. And here was Robin, star of a TV series, well brought up, elegant and, in the eyes of the boxer, stratospheres above him.

He lusted after her. And, oh so cleverly, she played hard to get.

For weeks she refused to sleep with him. When, finally, she relented, Tyson told everyone that he had discovered the difference between sex and making love. A few weeks later, Robin phoned to say she was pregnant. They married on February 7, 1988.

Within days, she had paid cash for a £2 million mansion 30 miles outside New York. Almost as quickly she gave Tyson the sad news – she had suffered a miscarriage. Their violent, ill-matched union ended a year later.

He told his friend, boxer José Torres, that his greatest punch was the one he gave Robin bouncing her off the walls of their bedroom. Yet his aggression towards women did not end or begin with Robin Givens. He confided In Torres that he liked to hurt women, liked to make them scream with pain when he had sex with them.

When wiser voices advised him that all he needed was a woman to love him, Tyson retorted: “I don’t want them to like me, I just want to screw them.” So far. Tyson appears to be the one who is being screwed. A list of women have threatened him with writs for sexual misbehaviour totalling $150 million.

As the money poured in and glitzy glamour of the Eighties spread Its temptations before him, Tyson ran into other troubles. He had an accident in New York and tried to give his expensive car to two policemen. They took it, but returned the car after being reprimanded.

He punched former opponent Mitch Green in an early-morning street quarrel so hard that he broke a bone in his right hand. And he ran into a tree in his sports car and knocked himself unconscious.

When we met, he was clearly anxious not to be portrayed as some raw kid fresh from the ghettos. He wanted me to know that, thanks to Camille and Cus, he had made it.

“I can hold a conversation, order fancy food, feel comfortable in a place like this,” he said, gesturing round the enormously lavish room. In the end, though, the darkness within him was not to be denied.

Urged on by the ghetto child inside him. The spoilt, indulged prince of the pack lost control. As he sat in front of the jury, he knew that the shadows were closing in on him.

But you can be sure that he doesn’t understand why or how this catastrophe has befallen him. That sort of enlightenment is yet to come. If it ever does.