Interview with John McEnroe, published in the Daily Mirror 14 June, 1982

Winning is Never having to say you’re sorry.

Winning is Never having to say you’re sorry.

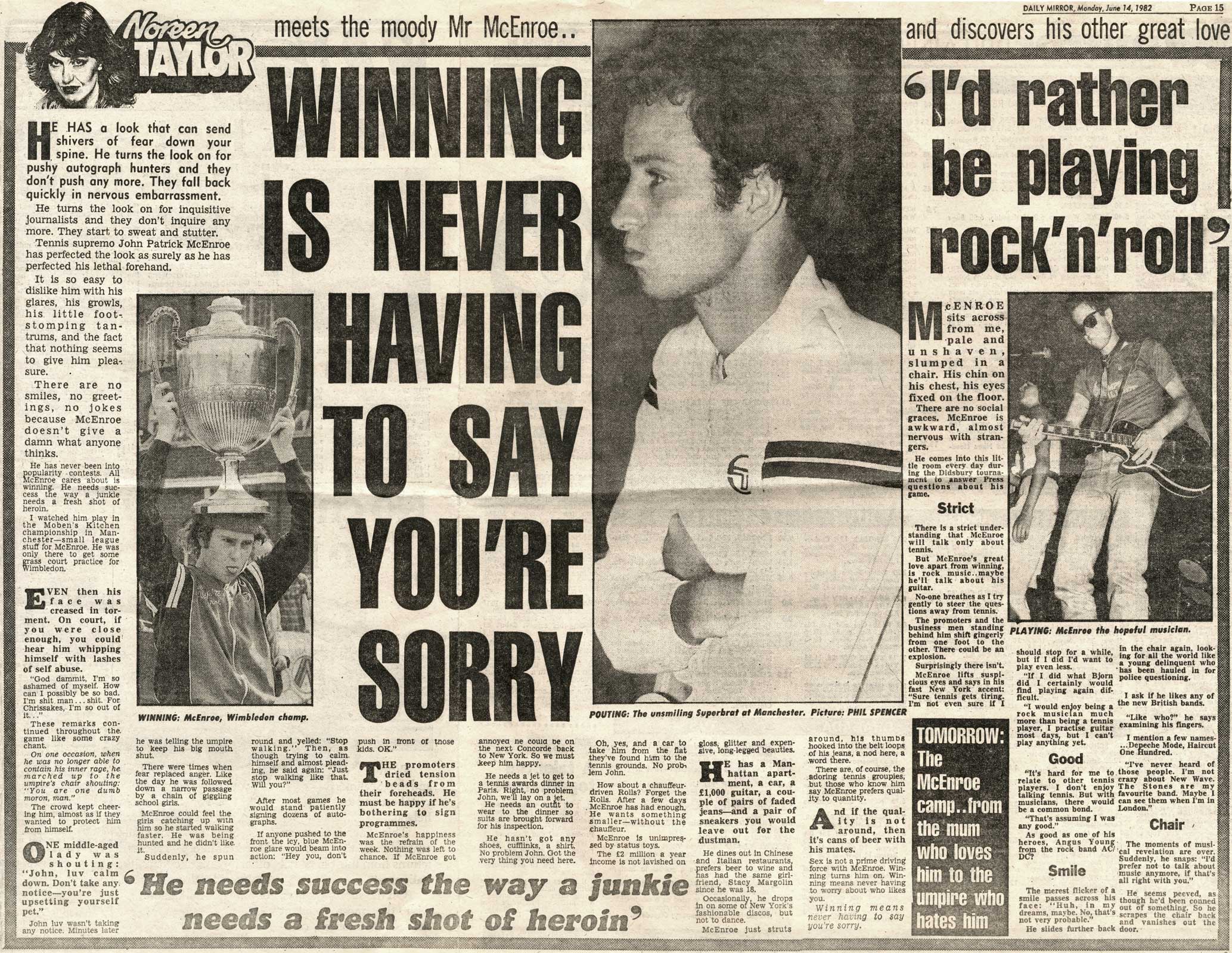

He has a look that can send shivers of fear down your spine. He turns the look on for pushy autograph hunters and they don’t push any more. They fall back quickly in nervous embarrassment. He turns the look on for inquisitive journalists and they don’t inquire any more. They start to sweat and stutter.

Tennis supremo John Patrick McEnroe has perfected the look as surely as he has perfected his lethal forehand. It is so easy to dislike him with his glares, his growls, his little foot-stomping tantrums, and the fact that nothing seems to give him pleasure.

There are no smiles, no greetings, no jokes because McEnroe doesn’t give a damn what anyone thinks. He has never been into popularity contests. All McEnroe cares about is winning. He needs success the way a junkie needs a fresh shot of heroin.

I watched him play in the Moben’s Kitchen championship in Manchester – small league stuff for McEnroe. He was only there to get some grass court practice for Wimbledon.

Even then, his face was creased in torment. On court, if you were close enough, you could hear him whipping himself with lashes of self-abuse. “God dammit. I’m so ashamed of myself. How can I possibly be so bad? I’m shit man… shit. For Chrissakes, I’m so out of it.”

These remarks continued throughout the game like some crazy chant. On one occasion, when he was no longer able to contain his inner rage, he marched up to the umpire’s chair shouting: “you are one dumb moron, man.” The crowd kept cheering him, almost as if they wanted to protect him from himself. One middle-aged lady was shouting: “John, luv calm down. Don’t take any notice – you’re just upsetting yourself pet.”

John luv wasn’t taking any notice. Minutes later he was telling the umpire to keep his big mouth shut. There were times when fear replaced anger. Like the day he was followed down a narrow passage by a chain of giggling school girls. McEnroe could feel the girls catching up with him so he started walking faster. He was being hunted and he didn’t like it. Suddenly, he spun round and yelled: “Stop walking.” Then, as though trying to calm himself and almost pleading, he said again: “Just stop walking like that. Will you?”

After most games he would stand patiently signing dozens of autographs. If anyone pushed to the front the icy blue McEnroe glare would beam into action: “Hey you, don’t push in front of those kids. OK.”

The promoters dried tension beads from their foreheads. He must be happy if he’s bothering to sign programmes. McEnroe’s happiness was the refrain of the week. Nothing was left to chance, if McEnroe got annoyed be could the on the next Concorde back to New York. So, we must keep him happy.

Oh, yes, and a car to take him from the flat they’ve found him to the tennis grounds. No problem, John. How about a chauffeur-driven Rolls? Forget the Rolls. After a few days, McEnroe has had enough.

He wants something smaller – without the chauffeur.

McEnroe is unimpressed by status toys. The £2 million a year income is not lavished on gloss, glitter and expensive long-legged beauties. He has a Manhattan apartment, a car, a $1,000 guitar, a couple of pairs of faded jeans—and a pair of sneakers you would leave out for the dustman.

He dines out in Chinese and Italian restaurants, prefers beer to wine and has had the same girlfriend, Stacy Margolin, since he was 18. Occasionally, he drops in on some of New York’s fashionable discos, but not to dance. McEnroe just struts around, his thumbs hooked into the belt loops of his jeans, a nod here, a word there. There are of course, the adoring tennis groupies, but those who know him say McEnroe prefers quality to quantity.

And if the quality is not around, then it’s cans of beer with his mates. Sex is not a prime driving force with McEnroe. Winning turns him on. Winning means never having to worry about who likes you. Winning means never having to say you’re sorry.

‘I’d rather be playing rock ‘n’ roll’

McEnroe sits across from me, pale and unshaven, slumped in a chair. His chin on his chest, his eyes fixed on the floor. There are no social graces. McEnroe is awkward, almost nervous with strangers.

He comes into this little room every day during the Didsbury tournament to answer Press questions about his game. There is a strict understanding that McEnroe will talk only about tennis.

But McEnroe’s great love apart from winning, is rock music… maybe

he’ll talk about his guitar. No-one breathes as I try gently to steer the questions away from tennis. The promoters and the business men standing behind him shift gingerly from one foot to the other. There could be an explosion. Surprisingly, there isn’t.

McEnroe lifts suspicious eyes and says in his fast New York accent: “Sure tennis gets tiring. I’m not even sure if I should stop for a while, but if I did I’d want to play even less. If I did what Bjorn did I certainly would find playing again difficult.

“I would enjoy being a rock musician much more than being a tennis player. I practise guitar most days, but I can’t play anything yet. It’s hard for me to relate to other tennis players. I don’t enjoy talking tennis. But with musicians, there would be a common bond. That’s assuming I was any good.”

As good as one of his heroes, Angus Young from the rock band AC/DC? The merest flicker of a smile passes across his face: “Huh, n my dreams, maybe. No, that’s not verv probable.” He slides further back in the chair again, looking for all the world like a young delinquent who has been hauled in for police questioning.

I ask if he likes any of the new British bands. “Like who?” he says, examining his fingers. I mention a few names: Depeche Mode, Haircut 100. “I’ve never heard of those people. I’m not crazy about New Wave. The Stones are my favourite band. Maybe I can see them when I’m in London.”

The moments of musical revelation are over. Suddenly he snaps: “I’d prefer not to talk about music anymore, if that’s all right with you.” He seems peeved, as though he’d been conned out of something. He scrapes the chair back and vanishes out the door.