Grey Gowrie | The Daily Mail Weekend magazine | January 2002

Few can be said to be on easier terms with the mechanics of the British establishment than Alexander Patrick Greysteil Hore-Ruthven, the Earl of Gowrie, or plain Grey Gowrie, as he is happy to be known.

Few can be said to be on easier terms with the mechanics of the British establishment than Alexander Patrick Greysteil Hore-Ruthven, the Earl of Gowrie, or plain Grey Gowrie, as he is happy to be known.

Born into the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, he served as a minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government, chaired the Arts Council and was chairman of Sotheby’s. What, then, is he doing in a small, charmless office at the furthest reaches of London’s Piccadilly Tube line? The answer is both simple and gratifying; for the 62-year-old peer, it is payback.

He is devoting as much time as he can to raising funds for a heart research centre for the man he credits with saving his life, Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub. Gowrie’s desk is in the grounds of Harefield Hospital, Middlesex, where, two years ago, he underwent a successful heart transplant which saved him from death. “I was prepared to die,” he says calmly. “It’s quite a shock to discover I’m still here.”

No amount of money nor his network of powerful worldwide contacts could have saved him. His only hope of life was a donor’s healthy heart, and of course the expertise of Yacoub and his superb Harefield team.

Now it is Gowrie’s turn to help Yacoub because Harefield is due to close. In order to support and continue his scientific research, the pioneering surgeon has created a charitable trust, independent of the NHS and relying largely on private donations. Enter Gowrie with his bulging Filofax of corporate heads, his management skills and his justifiably famous charm.

“What I’ve been through felt as lucky as winning the lottery and 1 want to make use of my incredible good fortune,” he says, rising unsteadily from behind his desk. Catching my surprised look, he explains: “The limping figure you see before you has nothing to do with my new heart. I happened to have a double whammy. I tripped on a television wire while waiting for my transplant operation and my left hip has never healed properly, probably due to the masses of immune-suppressant drugs I was on before the operation. It’s the only time in my spoilt, privileged life I’ve known pain.”

He brushes aside murmurs of sympathy, wanting instead to keep his attention focused on the project that has become paramount in his life, ensuring that Yacoub’s work and teachings can continue. He divides his time between his house in London’s Kensington, and his country home on the Welsh borders, where he writes poetry. His second collection will soon be published, just one of his many accomplishments.

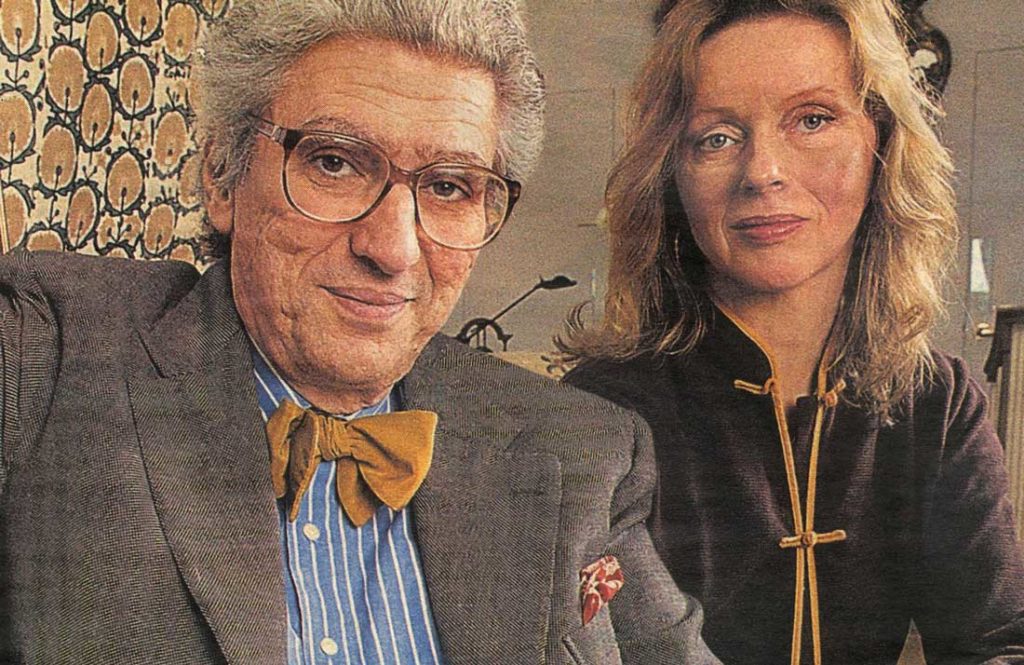

Dressed in smart tweeds, still handsome with melancholic dark eyes, a sallow skin and a shock of hair that turned grey at Oxford earning him the nickname, he reeks of aristocratic confidence and geniality. There are however contradictions within the stereotype.

Born in Dublin, he is an earl who has to earn his own fortune – famously and controversially remarking in 1985 that he couldn’t live in London on a salary of less than £33.000 a year. His father was killed in World War II and Gowrie inherited his title, but little else from his grandfather.

The family house in Wicklow, Castlemartin, had to be sold off. Gowrie’s childhood was spent in the tumbling splendour of a Georgian house in Donegal before going off to Eton. Although he spent most of his life in England, he takes pride in calling himself an Irishman. “I am a Nationalist, not a Unionist,” he says firmly.

How then did he square his political loyalties when he was junior minister under Thatcher during the 1981 hunger strike in which ten Republican prisoners died? He isn’t the least put out by the question.

“I was asked if I could help break the logjam and I did help. You see Thatcher knew nothing of the culture of Irish politics and I did.”

He lived his fast, power-fuelled life throughout the 1980s and 1990s, accepting the strains and pressures of his senior positions. Then came a dramatic turn of events. “Around the late 1980s I began to worry about my breathlessness. I didn’t smoke, and I thought my puffiness was due to stress and lack of exercise. I gave myself a good talking to and decided to hire a trainer.”

The trainer worked for his wife – German countess, Adelheid Grafin von der Schulenburg, known as Neiti. But, for Gowrie, it proved a big mistake which could have had dire consequences.

He explained: “If I had continued to exercise I would have killed myself. You see, I’d caught a virus which lodged in the right ventricle. I chose not to pay attention since bad tickers don’t run in my family. Instead I tried to continue with my life, telling everyone who asked that I felt fine, and spent eight years in denial. In fact, I was slowly dying, rather like an old car whose engine had run out of steam.”

By July 1999 Gowrie had become a seriously ill man whose organs were packing up. His kidneys had been damaged by the intake of drugs necessary to keep him alive, his legs had swoollen and tests revealed that his heart muscles had begun to fade.

“He was dying in front of my eyes,” said Neiti. His only hope was to convince Sir Magdi that he should be put on the heart transplant list at Harefield. “At 59, I was getting rather old for the transplant list. Few are carried out on people over 60.

“I was lucky. Before we went to meet Sir Magdi for the interview my wife, who thinks of me as a control freak, worried that I might disgrace myself. She told me, ‘Just listen to him. Don’t talk or try to tell this great man what to do. Remember he is the surgeon.’ At this point I knew I had only a few months to live so the interview was the most important of my life, more important than any job I’d gone after.

“I wasn’t put on the list immediately. Sir Magdi thought I should come into hospital to see if they could get me into good enough shape to withstand the operation if a heart should be found. Coming into Harefield meant submitting to hospital discipline, which I found calming, rather like being a child again.

“But it was harrowing for my family, especially for Neiti who drove to hospital every day with meals for me. Shameful, I know, but I never had to eat hospital food. During this punishing schedule, when Neiti felt she had to be strong for me, I told her to be as grumpy as she liked.

“I was never frightened or depressed in Harefield,” he says. “The fear came later because you do go through a terribly gloomy period after the operation. Instead I found a marvellous atmosphere, a feeling of camaraderie where everyone is on Death Row.

“Heart disease is no respecter of age. and my best friend in the ward was a 19-year-old man. In any case, I was very spoiled since lots of well-known people kept sending me crates of champagne, which ended up being stockpiled under the bed.”

After five months, Gowrie reached the top of the list and was told that his donor was to be a 32-year-old man who required a heart and lung transplant. “Knowing that my donor is now alive and kicking alleviated any guilt though, of course, somewhere down the chain, someone did die he says. I’d rather someone hadn’t died so I could live.”

Asked whether the operation has changed anything apart from his health, he pauses before replying. ‘No, I don’t think it has. I’ve never had regrets because they’re not useful thoughts. Anyway, I don’t think you change temperament easily. I’ve always been fatalistic, religious, never felt in control of my life, so, psychologically, I’m the same person.

“I’m always wary of people talking about how they have fought illness, because my attitude has been quite different. I’d describe it as submitting passively to the Almighty, almost drowning and drifting, and then finding my span extended.”

Perhaps then his span has been extended for a purpose? “The Harefield team are dedicated, brilliant men and women. If I can be of some service, ensuring that their work continues, then my survival will have been worthwhile.”