Nelson Mandela | The Daily Mirror | 16 April 1990

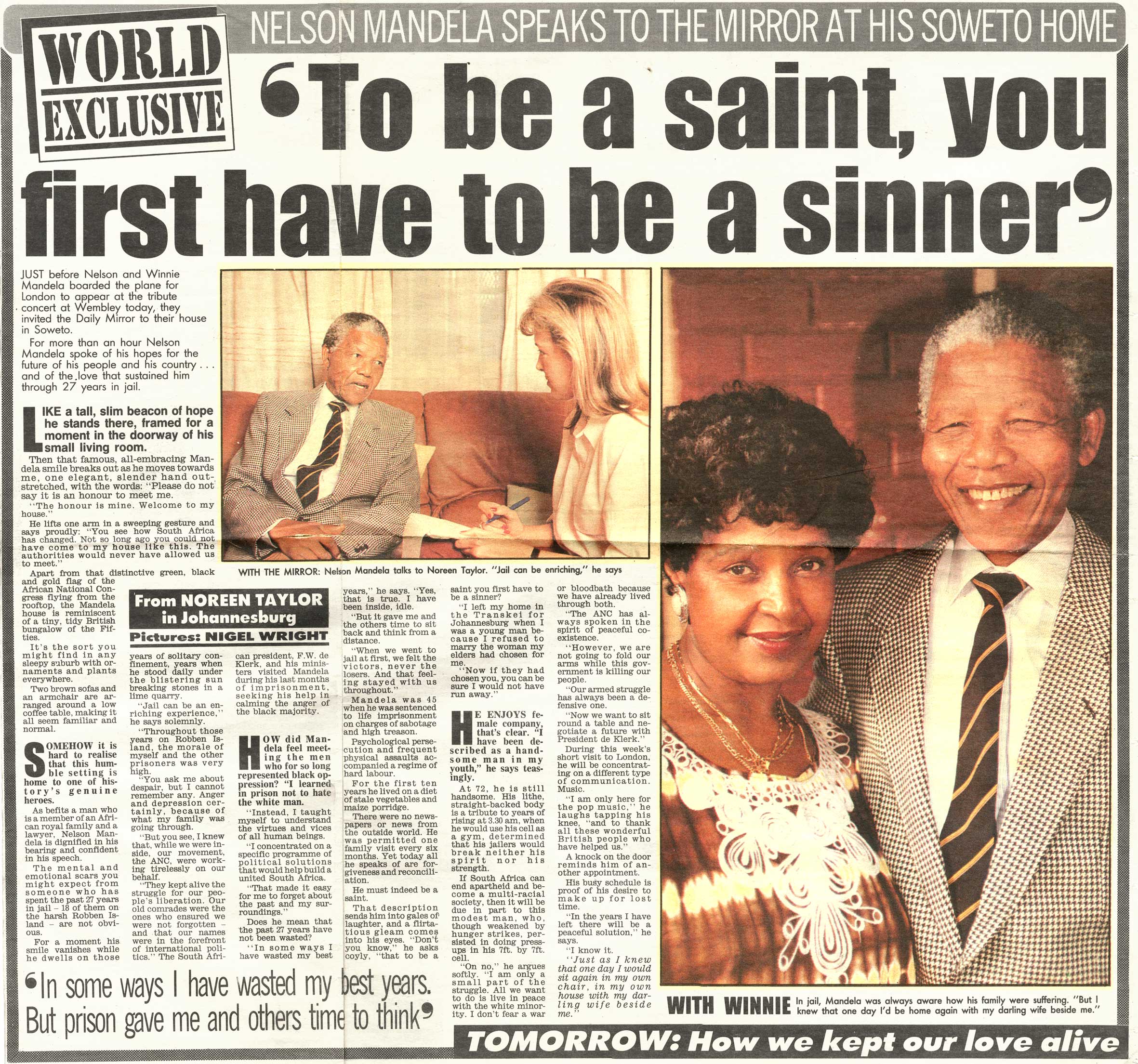

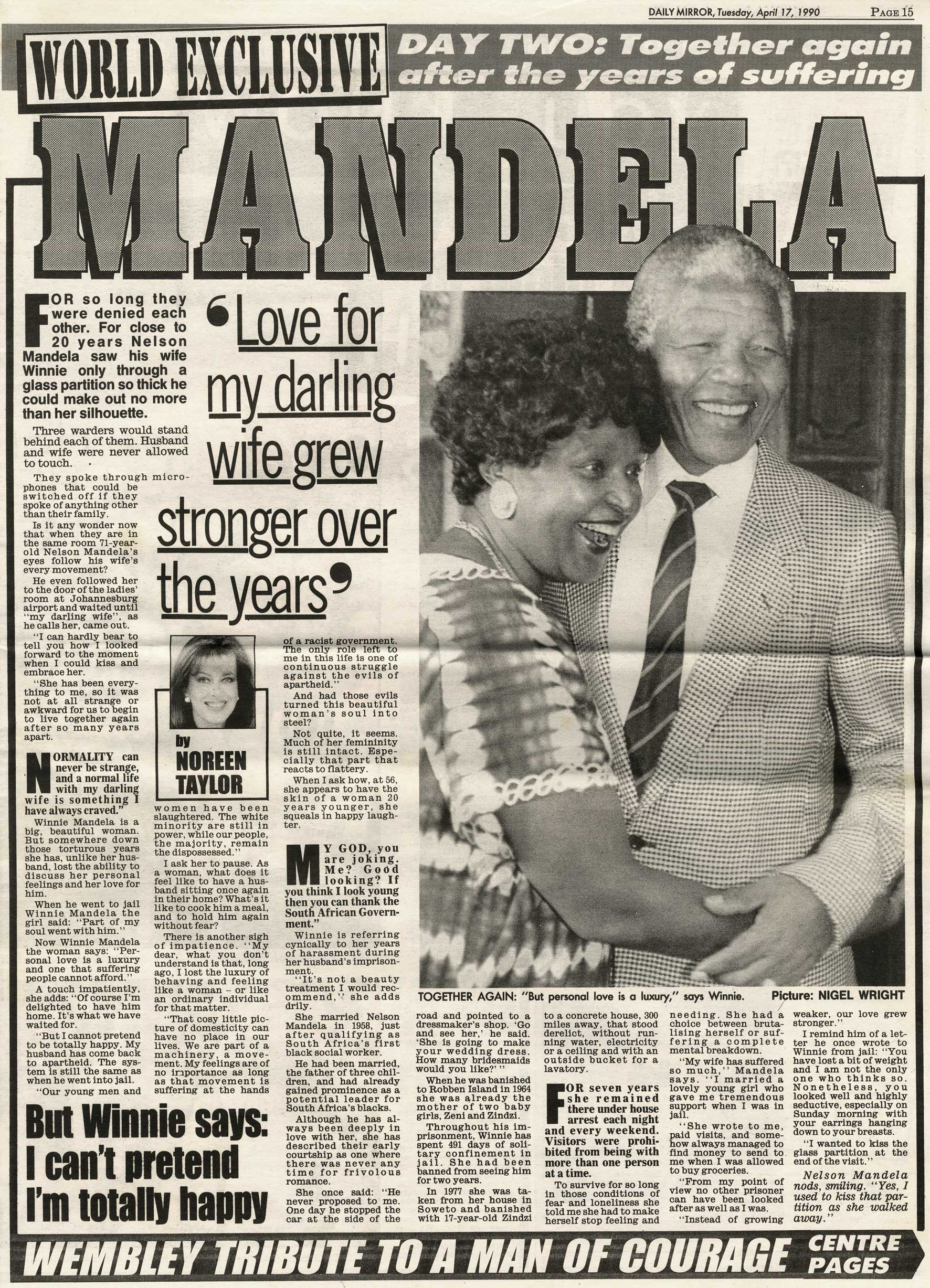

Just before Nelson and Winnie Mandela boarded the plane for London to appear at the tribute concert at Wembley today, they invited the Daily Mirror to their house in Soweto. For more than an hour Nelson Mandela spoke of his hopes for the future of his people and his country… and of the love that sustained him through 27 years in jail.

Just before Nelson and Winnie Mandela boarded the plane for London to appear at the tribute concert at Wembley today, they invited the Daily Mirror to their house in Soweto. For more than an hour Nelson Mandela spoke of his hopes for the future of his people and his country… and of the love that sustained him through 27 years in jail.

Like a tall, slim beacon of hope he stands there, framed for a moment in the doorway of his small living room. Then that famous, all-embracing Mandela smile breaks out as he moves towards me, one elegant, slender hand outstretched, with the words: “Please do not say it is an honour to meet me. The honour is mine. Welcome to my house.”

He lifts one arm in a sweeping gesture and says proudly: “You see how South Africa has changed. Not so long ago you could not have come to my house like this The authorities would never have allowed us to meet.”

Apart from that distinctive green, black and gold flag of the African National Congress flying from the rooftop, the Mandela house is reminiscent of a tiny, tidy British bungalow of the Fifties.

It’s the sort you might find in any sleepy suburb with ornaments and plants everywhere.

Two brown sofas and an armchair are arranged around a low coffee table, making it all seem familiar and normal. Somehow it is hard to realise that this humble setting is home to one of history’s genuine heroes.

As befits a man who is a member of an African royal family and a lawyer, Nelson Mandela is dignified in his bearing and confident in his speech

The mental and emotional scars you might expect from someone who has spent the past 27 years in jail – 18 of them on the harsh Robben Island – are not obvious. For a moment his smile vanishes while he dwells on those years of solitary confinement, years when he stood daily under the blistering sun breaking stones in a lime quarry.

“Jail can be an enriching experience,” he says solemnly. “Throughout those years on Robben Island, the morale of myself and the other prisoners was very high. You ask me about despair, but I cannot remember any.

“Jail can be an enriching experience,” he says solemnly. “Throughout those years on Robben Island, the morale of myself and the other prisoners was very high. You ask me about despair, but I cannot remember any.

“Anger and depression certainly, because of what my family was going through. But you see, I knew that, while we were inside our movement, the ANC, were working tirelessly on our behalf.

“They kept alive the struggle for our people’s liberation. Our old comrades were the ones who ensured we were not forgotten – and that our names were in the forefront of international politics.”

The South African president, FW de Klerk, and his ministers visited Mandela during his last months of imprisonment, seeking his help in calming the anger of the black majority.

How did Mandela feel meeting the men who for so long represented black oppression? “I learned in prison not to hate the white man. Instead, I taught myself to understand the virtues and vices of all human beings.

“I concentrated on a specific programme of political solutions that would help build a united South Africa. That made it easy for me to forget about the past and my surroundings.”

Does he mean that the past 27 years have not been wasted? “In some ways I have wasted my best years,” he says. “Yes, that is true. I have been inside, idle. But it gave me and the others time to sit back and think from a distance. When we went to jail at first, we felt the victors, never the losers. And that feeling stayed with us throughout.”

Mandela was 45 when he was sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of sabotage and high treason. Psychological persecution and frequent physical assaults accompanied a regime of hard labour. For the first ten years he lived on a diet of stale vegetables and maize porridge.

There were no newspapers or news from the outside world. He was permitted one family visit every six months Yet today, all he speaks of are forgiveness and reconciliation. He must indeed be a saint.

That description sends him into gales of laughter, and a flirtatious gleam comes into his eyes. “Don’t you know,” he asks coyly, “that to be a saint you first have to be a sinner.

“I left my home in the Transkei for Johannesburg when I was a young man because I refused to marry the woman my elders had chosen for me. Now if they had chosen you, you can be sure I would not have run away.”

He enjoys male company, that’s clear. “I have been described as a handsome man in my youth,” he says teasingly. At 72, he is still handsome. His lithe, straight-backed body is a tribute to years of rising at 3.30am, when he would use his cell as a gym, determined that his jailers would break neither his spirit not his strength.

If South Africa can end apartheid and become a multi-racial society, then it will be due in part to this modest man, who, though weakened by hunger strikes, persisted in doing press-ups in his 7ft by 7ft cell.

“Oh no,” he argues softly. “I am only a small part of the struggle All we want to do is live in peace with the white minority. I don’t fear a war or bloodbath because we have already lived through both. The ANC has always spoken in the spirit of peaceful co-existence.

“However, we are not going to fold our arms while this government is killing our people. Our armed struggle has always been a defensive one. Now we want to sit round a table and negotiate a future with President de Klerk.”

During this week’s short visit to London, he will be concentrating on a different type of communication. Music. “I am only here for the pop music,” he laughs tapping his knee, “and to thank all these wonderful British people who have helped us.”

A knock on the door reminds him of another appointment. His busy schedule is proof of his desire to make up for lost time. “In the years I have left there will be a peaceful solution,” he says.

“I know it. Just as I knew that one day I would sit again in my own chair, in my own house with my darling wife beside me.”