Joan Hirst, secretary to Noel Coward | The Times | 10 April 1998

Noel Coward called her Joanie. She called him “The Master”. And she still does. Although he died 25 years ago, Joan Hirst’s life has continued to revolve around the man she served faithfully for the previous 25 years as his key backroom girl.

Noel Coward called her Joanie. She called him “The Master”. And she still does. Although he died 25 years ago, Joan Hirst’s life has continued to revolve around the man she served faithfully for the previous 25 years as his key backroom girl.

Deferential and modest to the last, she deliberately plays down the significance of her role. “Stop And Fetch was my other nickname. That’s all I was. Not at all important.” In fact, Joan’s knowledge about Sir Noel Coward is considered to be so vital she has finally been persuaded to appear in a three-part TV documentary about his life.

She also helped BBC 2’s Arenawith research for the series which celebrates the British theatre legend’s extraordinary career and influence. Joan, first hired as a typist and general office dogsbody, eventually became a trusted member of Coward’s inner circle. She was so discreet that Coward entrusted her with all his personal papers, moving them to her London flat and effectively appointing her as his archivist.

Talking about The Master to outsiders is so unusual that the eighty- something Joan had to be persuaded. “This is not at all the sort of thing I would normally do. I didn’t want to. Then Graham Payn said I must.”

Payn, Sir Noel’s companion and heir with whom she remains close friends, is the only other surviving member of Coward’s clique.

“Graham convinced me it would be good for the cause, you see, especially now that Noel’s become rather fashionable with the young, and next year will be his centenary. One of the researchers explained to me that he’s currently perceived as cool, as in cool Britannia.”

Joan is hesitant, almost wary of telling her story. “I was only a backroom girl,” she likes to stress, “someone quite in awe of him.”

It isn’t easy for her to talk about the man regarded as one of this century’s cultural icons, simply because she never has. Not for years, not even to her family.

“I always kept my mouth shut because I’m not the sort of girl who tells all, though it’s a simple enough story.” Her discretion was part of an unspoken deal; it sprang from the loyalty she felt she owed Sir Noel and was overlaid with her generation’s diplomatic code which would have forbidden anything so brash as a memoir.

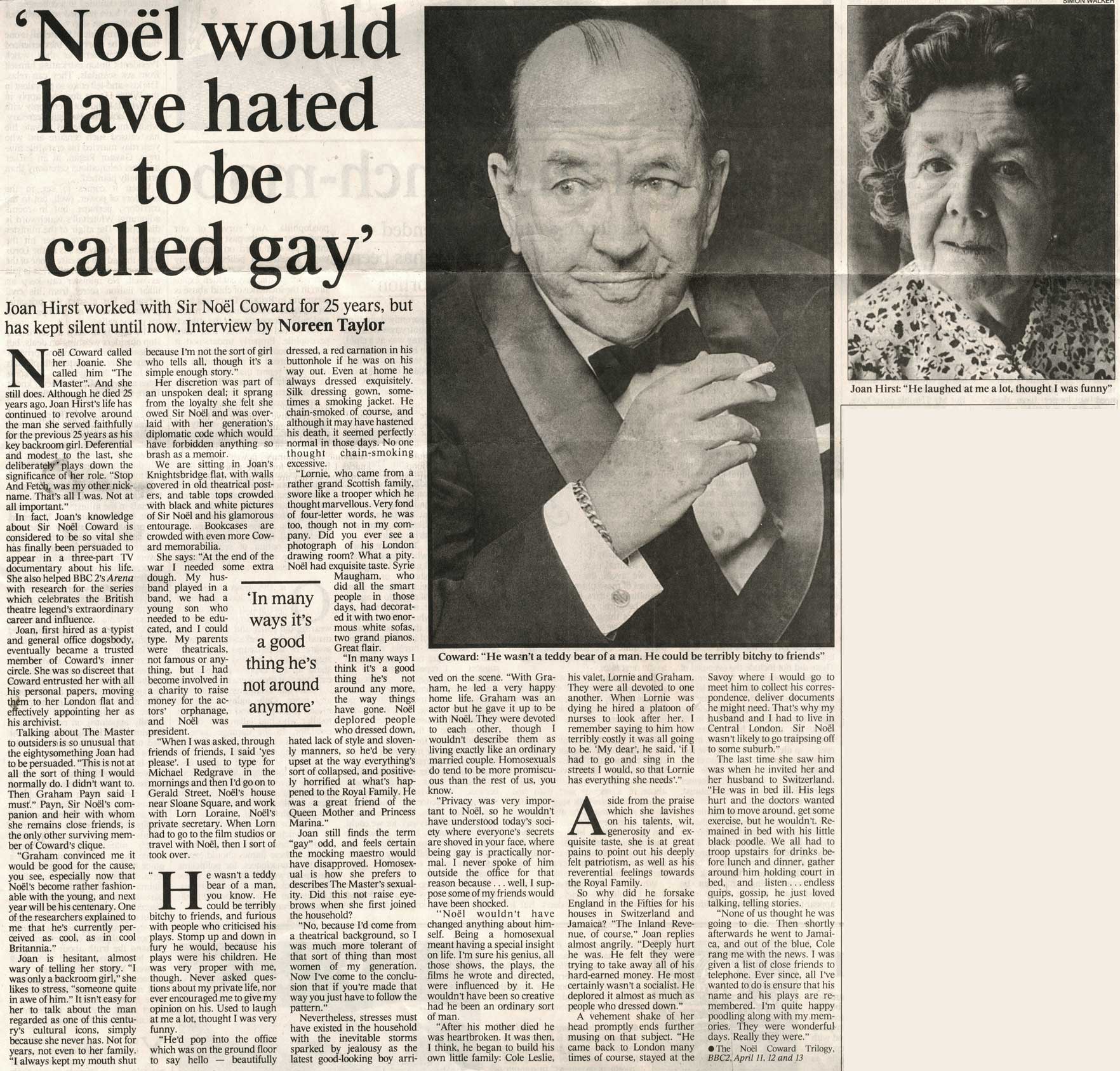

We are sitting in Joan’s Knightsbridge flat, with walls covered in old theatrical posters, and table tops crowded with black and white pictures of Sir Noel and his glamorous entourage. Bookcases are crowded with even more Coward memorabilia.

She says: “At the end of the war I needed some extra dough. My husband played in a band, we had a young son who needed to be educated, and I could type. My parents were theatricals, not famous or anything, but I had become involved in a charity to raise money for the actor’s orphanage, and Noel was president.

“When I was asked, through friends of friends, I said ‘yes please’. I used to type for Michael Redgrave in the mornings and then I’d go on to Gerald Street, Noel’s house near Sloane Square, and work with Lorn Loraine, Noel’s private secretary. When Lorn had to go to the film studios or travel with Noel, then I sort of took over.

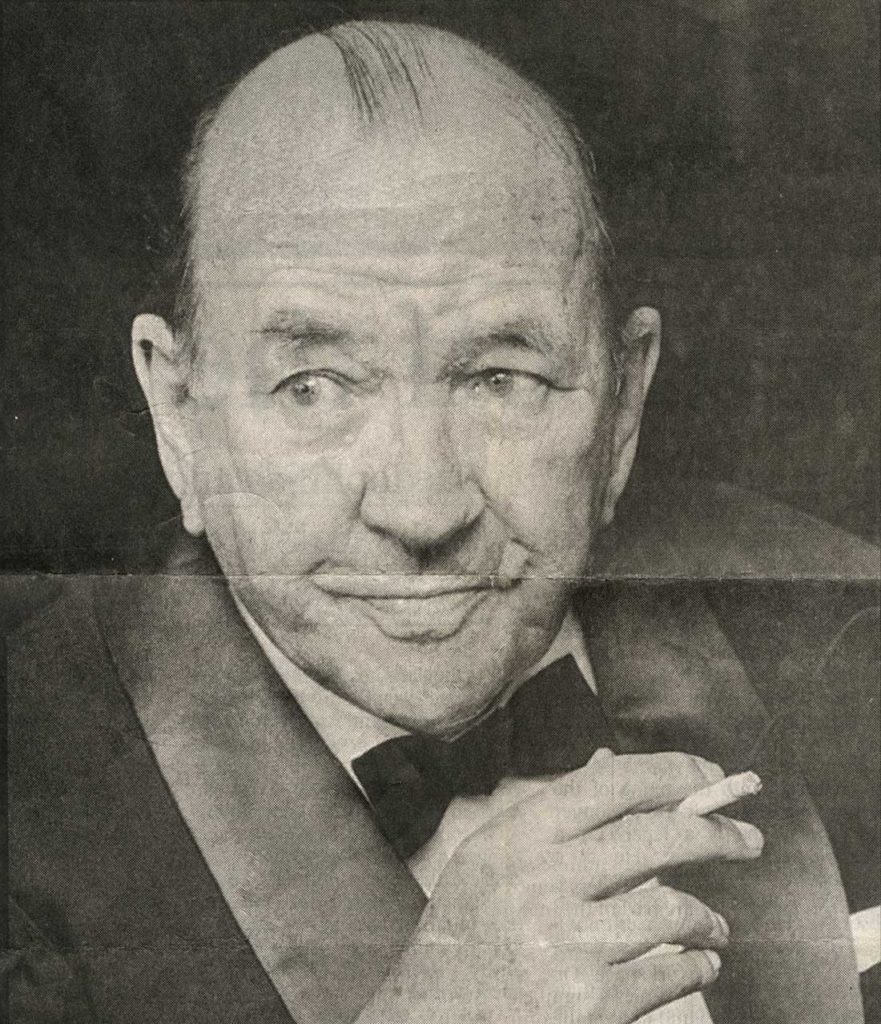

“He wasn’t a teddy bear of a man, you know. He could be terribly bitchy to friends, and furious with people who criticised his plays. Stomp up and down in fury he would, because his plays were his children. He was very proper with me, though. Never asked questions about my private life, nor ever encouraged me to give my opinion on his. Used to laugh at me a lot, thought I was very funny.

“He’d pop into the office which was on the ground floor to say hello – beautifully, dressed, a red carnation in his buttonhole if he was on his way out. Even at home he always dressed exquisitely. Silk dressing gown, sometimes a smoking jacket. He chain-smoked of course, and although it may have hastened his death, it seemed perfectly normal in those days. No one thought chain-smoking excessive.

“Lornie, who came from a rather grand Scottish family, swore like a trooper which he thought marvellous. Very fond of four-letter words, he was too, though not in my company. Did you ever see a photograph of his London drawing room? What a pity. Noel had exquisite taste.

“Syrie Maugham, who did all the smart people in those days, had decorated it with two enormous white sofas, two grand pianos. Great flair. In many ways I think it’s a good thing he’s not around anymore, the way things have gone.

“Noel deplored people who dressed down, hated lack of style and slovenly manners, so he’d be very upset at the way everything’s sort of collapsed, and positively horrified at what’s happened to the Royal Family. He was a great friend of the Queen Mother and Princess Marina.”

Joan still finds the term ‘gay’ odd, and feels certain the mocking maestro would have disapproved. Homosexual is how she prefers to describe The Master’s sexuality. Did this not raise eyebrows when she first joined the household?

“No, because I’d come from a theatrical background, so I was much more tolerant of that sort of thing than most women of my generation. Now I’ve come to the conclusion that if you’re made that way you just have to follow the pattern.”

Nevertheless, stresses must have existed in the household with the inevitable storms sparked by jealousy as the latest good-looking boy arrived on the scene. “With Graham, he led a very happy home life. Graham was an actor but he gave it up to be with Noel. They were devoted to each other, though I wouldn’t describe them as living exactly like an ordinary married couple. Homosexuals do tend to be more promiscuous than the rest of us, you know.

“Privacy was very important to Noel, so he wouldn’t have understood today’s society where everyone’s secrets are shoved in your face, where being gay is practically normal. I never spoke of him outside the office for that reason because… well, I suppose some of my friends would have been shocked. Noel wouldn’t have changed anything about himself. Being a homosexual meant having a special insight on life.

“I’m sure his genius, all those shows, the plays, the films he wrote and directed, were influenced by it. He wouldn’t have been so creative had he been an ordinary sort of man.

“After his mother died he was heartbroken. It was then, I think, he began to build his own little family: Cole Leslie, his valet, Lornie and Graham. They were all devoted to one another. When Lornie was dying he hired a platoon of nurses to look after her. I remember saying to him how terribly costly it was all going to be. ‘My dear’, he said, ‘if I had to go and sing in the streets I would, so that Lornie has everything she needs.’”

Aside from the praise which she lavishes on his talents, wit, generosity and exquisite taste, she is at great pains to point out his deeply felt patriotism, as well as his reverential feelings towards the Royal Family. So why did he forsake England in the Fifties for his houses in Switzerland and Jamaica?

“The Inland Revenue, of course,” Joan replies almost angrily. “Deeply hurt he was. He felt they were trying to take away all of his hard-earned money. He most certainly wasn’t a socialist. He deplored it almost as much as people who dressed down.”

A vehement shake of her head promptly ends further musing on that subject. “He came back to London many times of course, stayed at the

Savoy where I would go to meet him to collect his correspondence, deliver documents he might need. That’s why my husband and I had to live in Central London. Sir Noel wasn’t likely to go traipsing off to some suburb.”

The last time she saw him was when he invited her and her husband to Switzerland. “He was in bed ill. His legs hurt and the doctors wanted him to move around, get some exercise, but he wouldn’t. Remained in bed with his little black poodle. We all had to troop upstairs for drinks before lunch and dinner, gather around him holding court in bed, and listen… endless quips, gossip, he just loved talking, telling stories.

“None of us thought he was going to die. Then, shortly afterwards, he went to Jamaica, and out of the blue, Cole rang me with the news. I was given a list of close friends to telephone.

“Ever since, all I’ve wanted to do is ensure that his name and his plays are remembered. I’m quite happy poodling along with my, memories. They were wonderful days. Really they were.”