Profile of Queen Elizabeth I to mark her 40 years on the throne | The Daily Mirror | January 1992

A slight, young figure in black, still only 25, Elizabeth Alexandra Mary walked slowly down the aircraft steps on that cold February afternoon into her new life. A life as Monarch of Great Britain, Head of the Commonwealth and Defender of the Faith.

A slight, young figure in black, still only 25, Elizabeth Alexandra Mary walked slowly down the aircraft steps on that cold February afternoon into her new life. A life as Monarch of Great Britain, Head of the Commonwealth and Defender of the Faith.

“Shall I go down alone?” she had asked her uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, who had boarded the plane along with the Mountbattens to greet her and Philip. Even then, amidst her sadness, Elizabeth II demonstrated her innate skill at creating an impression of majesty.

That poignant first glimpse of the new Queen, alone, would provide an indelible memory. She seemed composed at first and then the camera caught a tremor of grief breaking through the mask of control. Waiting to greet this young woman, who was now their sovereign, were the stately elders who had served her beloved father, George VI.

Winston Churchill, Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, Foreign Secretary and Clement Attlee, leader of the Labour Party, stood in line, like elderly rooks. Relics of wars, of other times.

Elizabeth had already served her apprenticeship – unlike her father, who had never been trained for the role of sovereign since his accession was caused by his brother’s abdication. The role of Queen, however, was not one she expected to have thrust upon her so swiftly. Only a week before, she and the Duke of Edinburgh had set off on what was to be a tour of East Africa, Australia and New Zealand, a comparatively carefree couple.

The Royal Family had known the King had cancer but seemed certain he was not in any danger. When he died during the night at Sandringham, Elizabeth and Philip were at the Treetops Hotel in Kenya.

They had spent the night sitting on a 30-foot high platform, specially built into the trees, watching wildlife. When she came down from her tree-top vigil at 10am on February 6, Princess Elizabeth was Queen.

The news of the King’s death would not reach her until later in the day, when her husband asked her to accompany him on a riverside walk. They walked back and forth for about an hour. She was stunned, trying to come to terms with what this awesome news would mean to their lives. Philip, equally distraught, was described by an aide as looking as though “the whole world had dropped on him”.

On the returning flight, the Queen refused to change into the black that is always packed for foreign visits until the plane doors had practically opened. Wearing the outfit would not only force her to admit her father was dead. But that her freedom, and any personal life she might hope for, had died with him.

‘A fairy-tale monarch for a drab world still reeling from war’

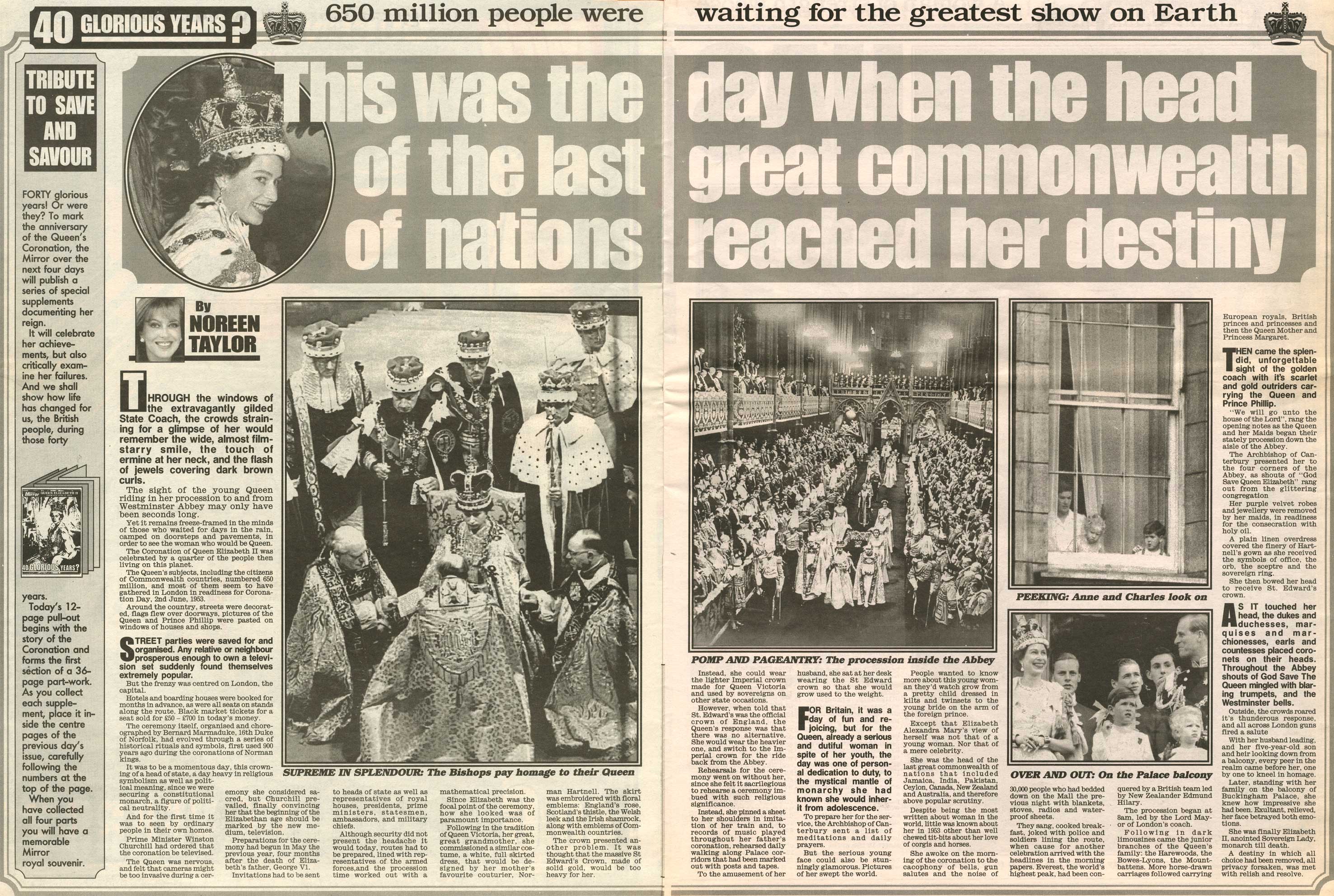

A fairy-tale queen for a new Elizabethan era – that is how Her Majesty was portrayed in her first formal portrait in one of the palace state rooms. A symbol for a nation tired of post-war austerity, of rationing and the rubble of bombed cities.

Wearing George IV’s diadem on her head and a full-skirted gown, a style made popular by her mother, Elizabeth II fulfilled the nation’s need for a new guiding spirit to lead them into an era of what they hoped would be one of peaceful prosperity.

The country was besotted by her. Greedy for news, gossip, pictures, her adoring public found no detail too trivial. People everywhere seemed so overwhelmed by this blend of glamour, youth and power that often a glimpse of the Queen during an engagement would have onlookers in tears.

In the months following her accession, the Queen found herself struggling to combine the roles of Monarch, wife and mother. Not that there was ever any doubt as to what would take precedence. She did, after all, belong to that world where children were looked after by servants and became used to absentee parents.

But she minded the short periods she was only ever able to spend with Prince Charles and Princess Anne, who were only aged four and two when she became Queen.

But she minded the short periods she was only ever able to spend with Prince Charles and Princess Anne, who were only aged four and two when she became Queen.

It was a very different royal scenario from the intimate one that exists now between Diana and her sons. The pressures of being such a young Queen were heavy.

Returning home after the long Commonwealth tour of 1953-54, the Queen leaned down to scoop her son into her arms when the child stepped back and offered her his hand to shake. Yet a loving bond was formed between them.

They revelled in each other’s company, sharing a love of the outdoors and country pursuits. As they grew older, her dual roles as Monarch and mother became less confusing. Charles and Anne bowed and curtsied to one. But that did not prevent them enjoying a surprising closeness to the other.

The way we were

During the Fifties, we were deeply envious of Americans who lived, it seemed to us, a life of outrageous glamour. They drove around in pastel-coloured Cadillac convertibles, while we, the few who could afford to, squeezed into prim black box-like Astons.

And then an explosion took place in our fusty, old society. An explosion with a fall-out that gave us rock ‘n’ roll. Bill Haley on the jukebox, the jiving teenager and even more reason than ever to envy them. Our teenagers based their identity on their US counterparts. Jeans, leather jackets, ponytails, crew cuts, sneakers, Coca Cola and hamburgers – these all came from the great god Yankee. And when it came to sex symbols, it was simply no contest.

They had Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando, Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. And what did we have? Tommy Steele, Dirk Bogarde, Diana Dors and someone called Vera Day. Of course, we copied American slang and values. We felt we knew everything about them, since the cinema was US-dominated and one of our prime sources of entertainment and escapism.

There was plenty to escape from. A snobbish, class-ridden society and food-rationing that lasted until 1953. The war had left us with a housing shortage, so young married couples often had to rent a room in their parents’ already crowded homes.

Nine pounds was considered a decent weekly wage. But then a half pint of beer cost 4p, an average-sized house, £2,000, shoes £1.50p and a week in a holiday camp £5. Meanwhile, the American Wannabee syndrome had plenty to feed on.

Nine pounds was considered a decent weekly wage. But then a half pint of beer cost 4p, an average-sized house, £2,000, shoes £1.50p and a week in a holiday camp £5. Meanwhile, the American Wannabee syndrome had plenty to feed on.

We knew from the cinema and emigrant relatives that Americans lived in large airy houses with swimming pools and kitchens filled with alien gadgets like refrigerators, washing machines and dishwashers.

White telephones sat beside their beds, while we had to traipse to a telephone box a couple of streets away. Our living standards were not dissimilar to one of today’s eastern European countries. Our beliefs were simple and Christian-led. Feminism had not entered our thoughts.

Divorce was rare, an option only for the very rich or the morally Bankrupt. Marriage and motherhood were still the highest callings a woman could aspire to. There was no contraceptive pill, abortion was a crime, sought only by the desperate in unhygienic back rooms.

Babies born out of wedlock suffered the stigma of being illegitimate.

Yet the way we were was not without its compensation. Violent crime, especially against women, bore no relation to today’s statistics.

We were a more naive people, easily impressed, and sometimes cowered by those we believed to be our betters. The Fifties, the first decade after the war, was also probably the last decade of innocence.