Magdi Yacoub | The Daily Mirror | July 1993

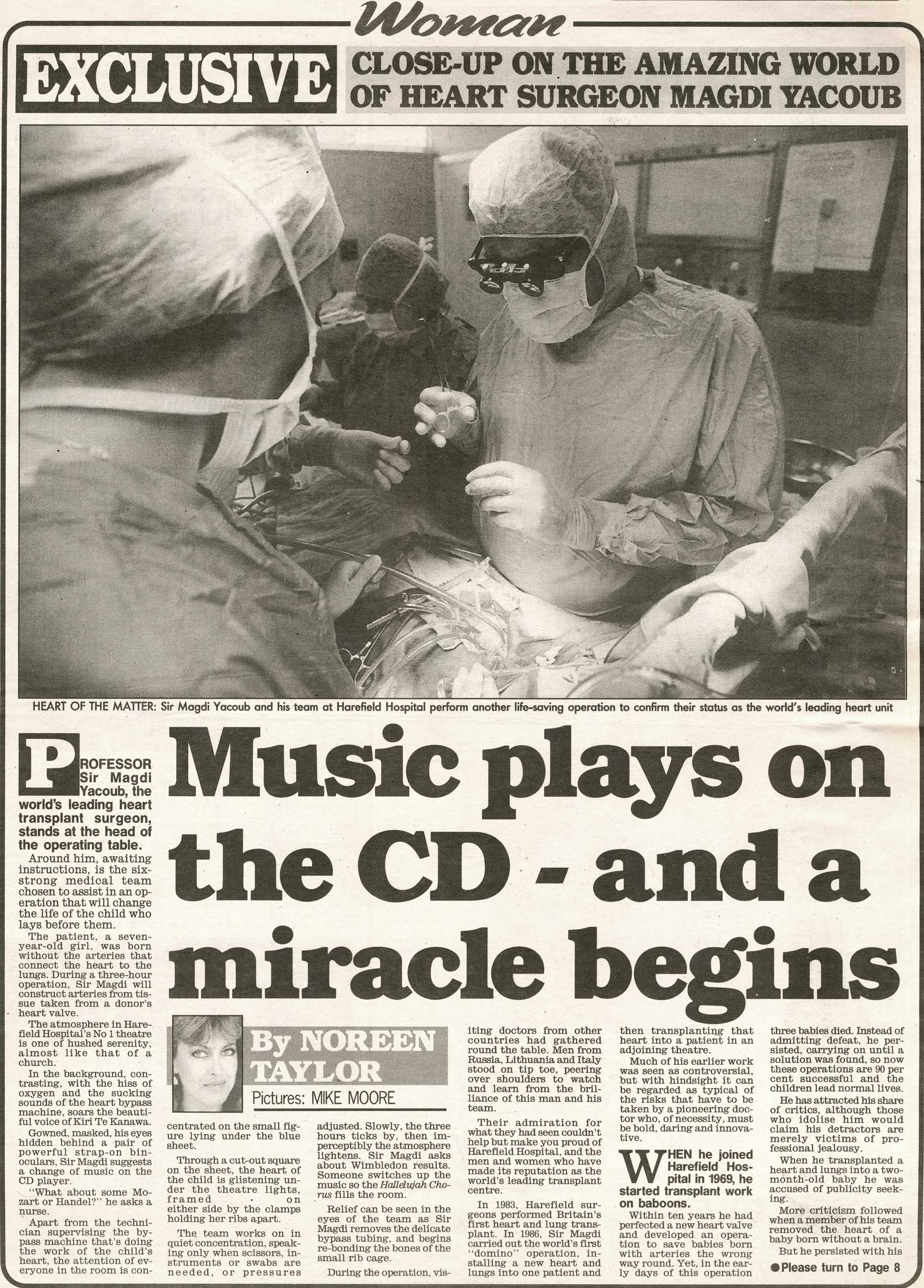

Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub, the world’s leading heart transplant surgeon, stands at the head of the operating table. Around him, awaiting instructions is the six-strong medical team chosen to assist in an operation that will change the life of the child who lays before them.

Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub, the world’s leading heart transplant surgeon, stands at the head of the operating table. Around him, awaiting instructions is the six-strong medical team chosen to assist in an operation that will change the life of the child who lays before them.

The patient, a seven-year-old girl, was born without the arteries that connect the heart to the lungs. During a three-hour operation, Sir Magdi will construct arteries from tissue taken from a donor’s heart valve. The atmosphere in Harefield Hospital’s No 1 theatre is one of hushed serenity, almost like that of a church.

In the background, contrasting with the hiss of oxygen and the sucking sounds of the heart by-pass machine, soars the beautiful voice of Kiri Te Kanawa. Gowned, masked, his eyes hidden behind a pair of powerful strap-on binoculars, Sir Magdi suggests a change of music on the CD player. “What about some Mozart or Handel?” he asks a nurse.

Apart from the technician supervising the by-pass machine that’s doing the work of the child’s heart, the attention of everyone in the room is concentrated on the small figure lying under the blue sheet.

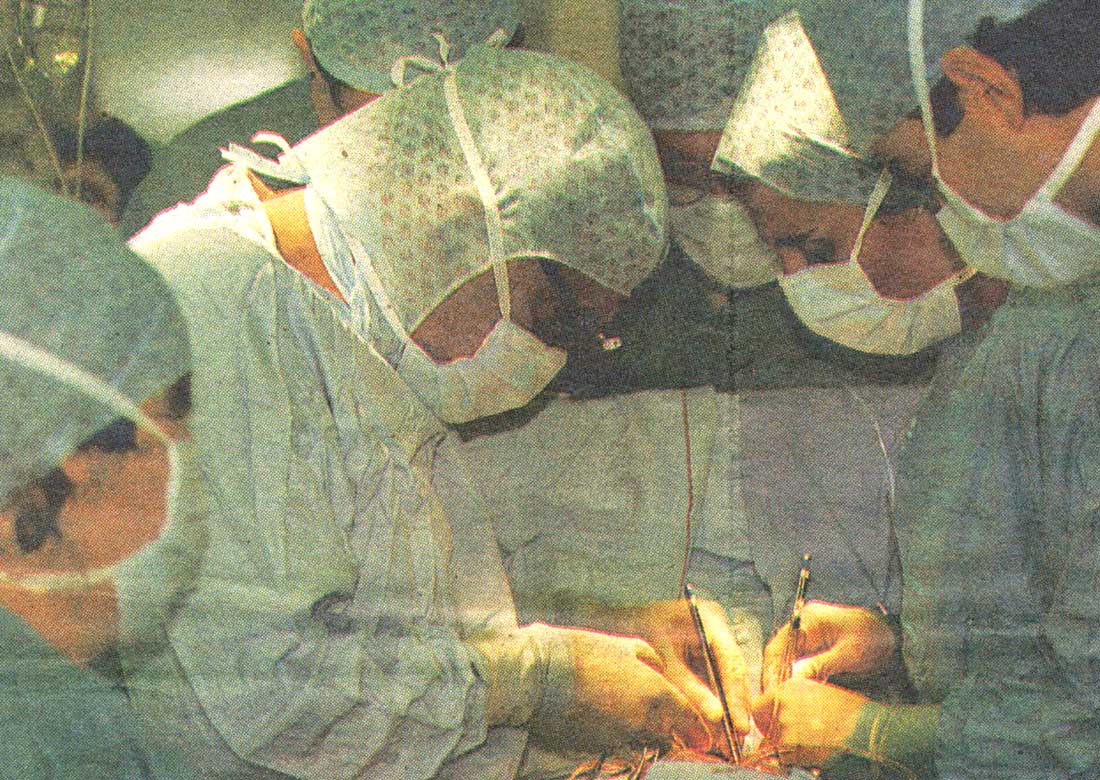

Through a cut-out square on the sheet, the heart of the child is glistening under the theatre lights – framed on either side by the clamps holding her ribs apart. The team works on in quiet concentration, speaking only when scissors, instruments or swabs are needed, or pressures adjusted. Slowly, the three hours tick by, then imperceptibly the atmosphere lightens.

Sir Magdi asks about Wimbledon results. Someone switches up the music so the Hallelujah Chorusfills the room. Relief can be seen in the eyes of the team as Sir Magdi removes the delicate bypass tubing and begins re-bonding the bones of the small rib cage.

During the operation, visiting doctors from other countries had gathered round the table. Men from Russia, Lithuania and Italy stood on tip toe, peering over shoulders to watch and learn from the brilliance of this man and his team.

Their admiration for what they had seen couldn’t help but make you proud of Harefield Hospital, and the men and women who have made its reputation as the world’s leading transplant centre. In 1983, Harefield surgeons performed Britain’s first heart and lung transplant. In 1986, Sir Magdi carried out the world’s first “domino” operation, installing a new heart and lungs into one patient then transplanting that heart into a patient in an adjoining theatre.

Much of his earlier work was seen as controversial, but with hindsight it can be regarded as typical of the risks that have to be taken by a pioneering doctor who, of necessity, must be bold, daring and innovative

When he joined Harefield Hospital in 1969, he started transplant work on baboons. Within ten years he had perfected a new heart valve and developed an operation to save babies born with arteries the wrong way round. Yet, in the early days of this operation three babies died. Instead of admitting defeat he persisted, carrying on until a solution was found, so now these operations are 90 per cent successful and the children lead normal lives.

He has attracted his share of critics, although those who idolise him would claim his detractors are merely victims of professional jealousy. When he transplanted a heart and lungs into a two-month-old baby he was accused of publicity seeking.

More criticism followed when a member of his team removed the heart of a baby born without a brain. But he persisted with his pioneer work, and can now be proud of the lives saved by what was once thought of by more orthodox figures as nothing other than showmanship.

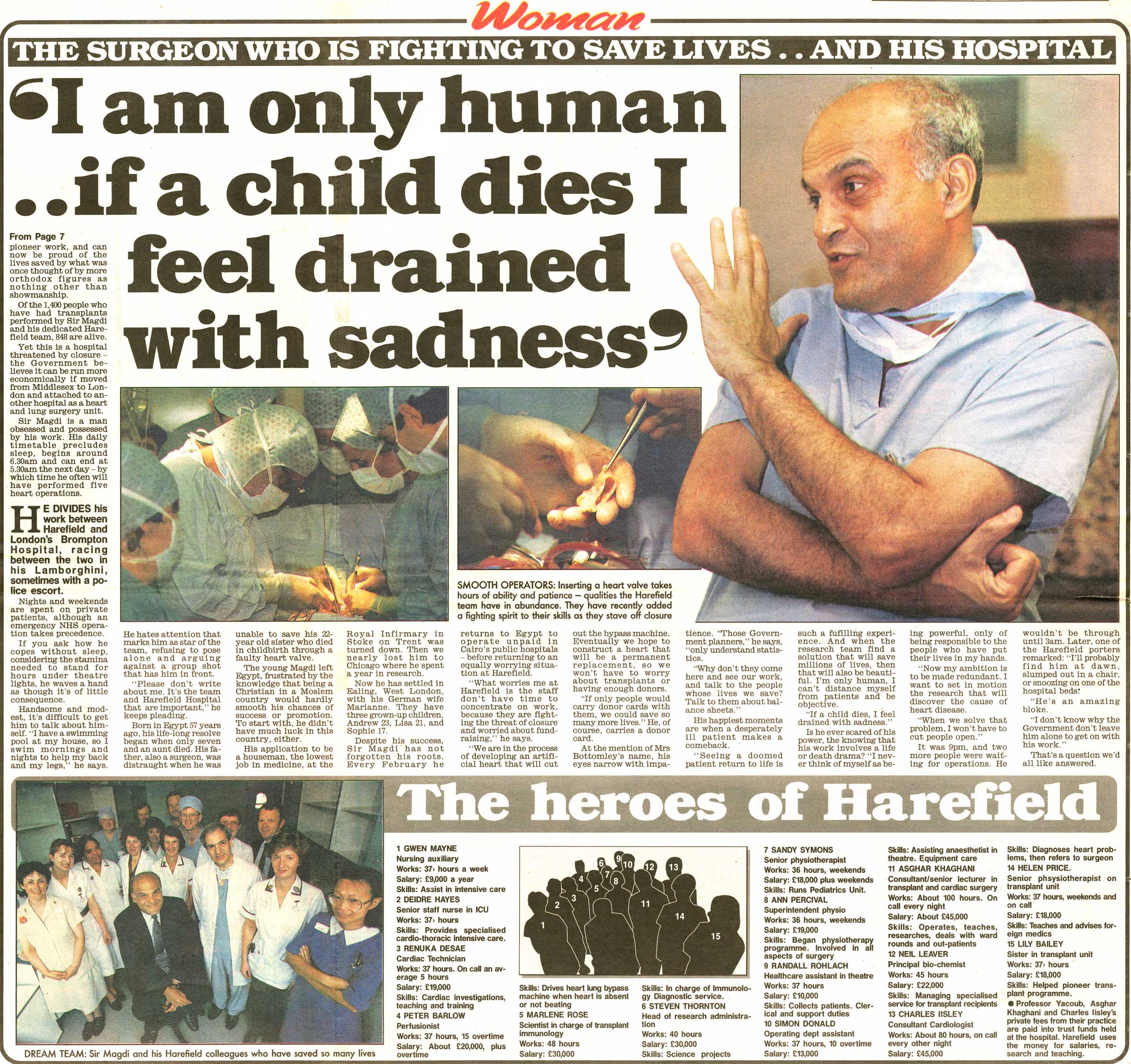

Of the 1,400 people who have had transplants performed by Sir Magdi and his dedicated Harefield team, 848 are alive. Yet this is a hospital threatened by closure – the Government believes it can be run more economically if moved from Middlesex to London and attached to another hospital as a heart and lung surgery unit.

Sir Magdi is a man obsessed and possessed by his work. His daily timetable which precludes sleep, begins around 6.30am and can end at 5.30am the next day – by which time he will often have performed five heart operations.

He divides his work between Harefield and London’s Brompton Hospital, racing between the two in his Lamborghini, sometimes with a police escort. Nights and weekends are spent on private patients although an emergency NHS operation takes precedence.

If you ask how he copes without sleep considering the stamina needed to stand for hours under theatre lights he waves a hand as though it’s of little consequence. Handsome and modest, it’s difficult to get him to talk about himself.

“I have a swimming pool at my house, and I swim most mornings and nights to help my back and my legs,” he says. He hates attention that marks him as star of the team, refusing to pose alone and arguing against a group shot that has him in front. “Please don’t write about me. It’s the team and Harefield Hospital that are important,” he pleads.

Born in Egypt 57 years ago, his lifelong resolve began when he was only seven and an aunt died. His father, also a surgeon, was distraught when he was unable to save his 22-year old sister who died in child-birth through a year a faulty heart valve.

The young Magdi left Egypt, frustrated by the knowledge that being a Christian in a Moslem country would hardly smooth his chances of success or promotion. To start with, he didn’t have much luck in this country, either. His application to be houseman, the lowest job in medicine, at the Royal Infirmary in Stoke on Trent was turned was turned down.

Then we nearly lost him to Chicago where he spent a year in research. Now he has settled in Ealing, West London, with his German wife, Marianne. They have three grown-up children, Andrew 23, Lisa, 21 and Sophie 17.

Despite his success, Sir Magdi has not forgotten his roots. Every February he returns to Egypt to operate unpaid in Cairo’s public hospitals before returning to an equally worrying situation at Harefield. “What worries me at Harefield is that the staff don’t have time to concentrate on work, because they are fighting the threat of closure and worried about fund-raising,” he says.

“We are in the process of developing an artificial heart that will cut out the bypass machine. Eventually we hope to construct a heart that will be a permanent replacement so we won’t have to worry about transplants or having enough donors. If only people would carry donor cards with them, we could save so many more lives.” He, of course carries a donor card.

At the mention of Mrs Bottomley’s name, his eyes narrow with impatience. “Those Government planners,” he says, “only understand statistics. Why don’t they come here and see our work, and talk to the people whose lives we save? Talk to them about balance sheets.”

His happiest moments are when a desperately ill patient makes comeback. “Seeing a doomed patient return to life is such a humbling experience. And when the research team find a solution that will save millions of lives, then that will also be beautiful. I’m only human, I can’t distance myself from patients and be objective. If a child dies, I feel drained with sadness.”

Is he ever scared of the knowing that his work involves a life or death drama? “I never think of myself as being powerful, only of being responsible to the people who have put their lives in my hands.

“Now my ambition is to be made redundant. I want to set in motion the research that will discover the cause of heart disease. When we solve that problem, I won’t have to cut people open.”

It was 9pm, and two more people were waiting for operations. He wouldn’t be through until 3am. Later, one of the Harefield porters remarked: “I probably find him at dawn, slumped in a chair, or snoozing on one of the hospital beds. I don’t know why the Government don’t leave him alone to get on with his work.” That’s a question we would all want answered.