Susan McKay | The Times | July 2000

Going back to our roots is often a more discomforting and distressing journey than we imagine at the outset. Nostalgia fills us with preconceptions and, even if apprehensive, we’re fairly sure we know what we will find.

Going back to our roots is often a more discomforting and distressing journey than we imagine at the outset. Nostalgia fills us with preconceptions and, even if apprehensive, we’re fairly sure we know what we will find.

In Susan McKay’s case, that was certainly true. After all, the place and the people she had left behind formed, in a very real sense, part of her work. They also happen to be one of the most publicised, but perhaps least well understood, groups of people in the world: the Protestant people of Northern Ireland.

Even so, despite her knowledge, her family ties, her happy memories of school friends, McKay’s odyssey both shocked her and shamed her.

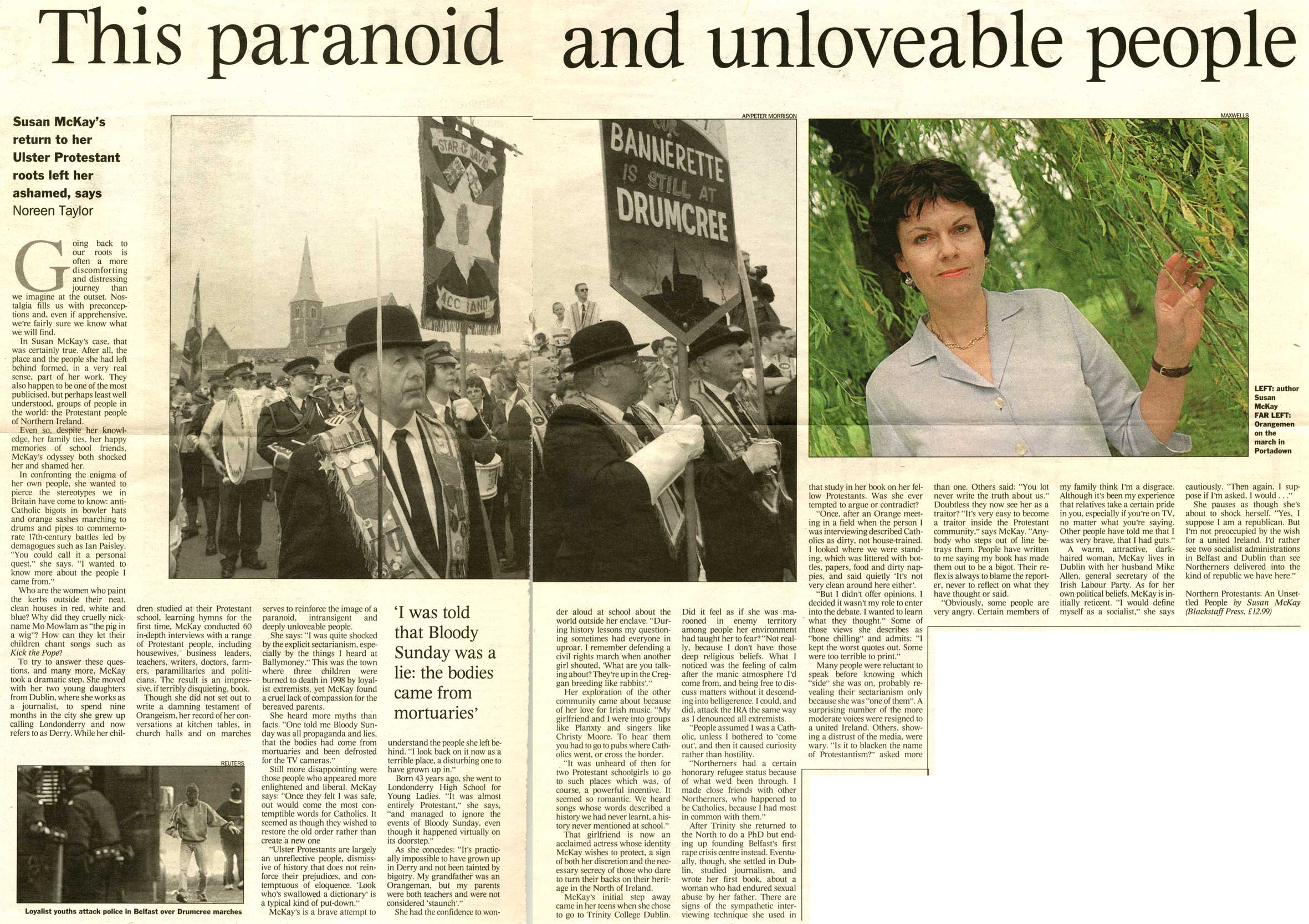

In confronting the enigma of her own people, she wanted to pierce the stereotypes we in Britain have come to know: anti-Catholic bigots in bowler hats and orange sashes marching to drums and pipes to commemorate 17th-century battles led by demagogues such as Ian Paisley.

“You could call it a personal quest,” she says. “I wanted to know more about the people I came from.” Who are the women who paint the kerbs outside their neat, clean houses in red, white and blue? Why did they cruelly nickname Mo Mowlam as “the pig in a wig”? How can they let their children chant songs such as Kick the Pope?”

To try to answer these questions, and many more, McKay took a dramatic step. She moved with her two young daughters from Dublin, where she works as a journalist, to spend nine months in the city she grew up calling Londonderry and now refers to as Derry.

While her children studied at their Protestant school, learning hymns for the first time, McKay conducted 60 in-depth interviews with a range of Protestant people, including housewives, business leaders, teachers, writers, doctors, farmers, paramilitaries and politicians. The result is an impressive, if terribly disquieting, book.

Though she did not set out to write a damning testament of Orangeism, her record of her conversations at kitchen tables, in church halls and on marches serves to reinforce the image of a paranoid, intransigent and deeply unloveable people.

She says: “1 was quite shocked by the explicit sectarianism, especially by the things I heard at Ballymoney.” This was the town where three children were burned to death in 1998 by loyalist extremists, yet McKay found a cruel lack of compassion for the bereaved parents.

She heard more myths than facts. “One person told me Bloody Sunday was all propaganda and lies, that the bodies had come from mortuaries and been defrosted for the TV cameras.”

Still more disappointing were those people who appeared more enlightened and liberal. McKay says: “Once they felt I was safe, out would come the most contemptible words for Catholics. It seemed as though they wished to restore the old order rather than create a new one.

“Ulster Protestants are largely an unreflective people, dismissive of history that does not reinforce their prejudices, and contemptuous of eloquence. ‘Look who’s swallowed a dictionary’ is a typical kind of put-down.”

McKay’s is a brave attempt to understand the people she left behind. “I look back on it now as a terrible place, a disturbing one to have grown up in.”

Born 43 years ago, she went to Londonderry High School for Young Ladies. “It was almost entirely Protestant,” she says, “and managed to ignore the events of Bloody Sunday, even though it happened virtually on its doorstep.”

As she concedes: “It’s practically impossible to have grown up in Derry and not been tainted by bigotry. My grandfather was an Orangeman, but my parents were both teachers and were not considered ‘staunch’.”

She had the confidence to wonder aloud at school about the world outside her enclave. “During history lessons my questioning sometimes had everyone in uproar. I remember defending a civil rights march when another girl shouted, ‘What are you talking about? They’re up in the Creggan breeding like rabbits’.”

Her exploration of the other community came about because of her love for Irish music. “My girlfriend and I were into groups like Planxty and singers like Christy Moore. To hear them you had to go to pubs where Catholics went or cross the border.”

It was unheard of then for two Protestant schoolgirls to go to such places which was, of course, a powerful incentive. It seemed so romantic. We heard songs whose words described a history we had never learnt, a history never mentioned at school.”

That girlfriend is now an acclaimed actress whose identity McKay wishes to protect, a sign of both her discretion and the necessary secrecy of those who dare to turn their backs on their heritage in the North of Ireland. McKay’s initial step away came in her teens when she chose to go to Trinity College Dublin.

Did it feel as if she was marooned in enemy territory among people her environment had taught her to fear? “Not really, because I don’t have those deep religious beliefs. What 1 noticed was the feeling of calm after the manic atmosphere I’d come from, and being free to discuss matters without it descending into belligerence.

“I could, and did, attack the IRA the same way as I denounced all extremists. People assumed I was a Catholic, unless I bothered to ‘come out’, and then it caused curiosity rather than hostility.

“Northerners had a certain honorary refugee status because of what we’d been through. I made close friends with other Northerners who happened to be Catholics because I had most in common with them.”

After Trinity she returned to the North to do her PhD but ended up founding Belfast’s first rape crises centre, instead. Eventually, she returned to Dublin, studied journalism and wrote her first book about a woman who had endured sexual abuse by her father.

There are signs of the sympathetic interviewing technique she used in

that study in her book on her fellow Protestants. Was she ever tempted to argue or contradict? “Once, after an Orange meeting in a field when the person I was interviewing described Catholics as dirty, not house-trained. I looked where we were standing, which was littered with bottles, papers, food and dirty nappies, and said quietly ‘It’s not very clean around here either’.”

But I didn’t offer opinions. I decided it wasn’t my role to enter into the debate. I wanted to learn what they thought.” Some of those views she describes as “bone chilling” and admits: “I kept the worst quotes out. Some were too terrible to print.”

Many people were reluctant to speak before knowing which “side” she was on, probably revealing their sectarianism only because she was “one of them’. A surprising number of the more moderate voices were resigned to a united Ireland. Others, showing a distrust of the media, were wary.

“Is it to blacken the name of Protestantism?” asked more than one.

Others said: “You lot never write the truth about us.” Doubtless they now see her as a traitor? “It’s very easy to become a traitor inside the Protestant community,” says McKay.

“Anybody who steps out of line betrays them. People have written to me saying my book has made them out to be a bigot. Their reflex is always to blame the reporter, never to reflect on what they have thought or said.

“Obviously, some people are very angry. Certain members of my family think I’m a disgrace, it’s been my experience that relatives take a certain pride in you, especially if you are on TV, no matter what you are saying. Other people have told me that I was very brave, that I had guts.”

A warm, attractive, dark-haired woman, McKay lives in Dublin with her husband Mike Allen, general secretary of the Irish Labour Party. As for her own political beliefs, McKay is initially reticent. “I would define myself as a socialist,” she says cautiously. “Then again, I suppose if I’m asked, I would…”

She pauses as though she’s about to shock herself. “Yes, I suppose I am a republican. But I’m not preoccupied by the wish for a united Ireland. I’d rather see two socialist administrations in Belfast and Dublin than see Northerners delivered into the kind of republic we have here.”