Arthur Scargill | The Daily Mirror | November 1980

Arthur Scargill raised both arms as though nailed to a cross. “Tell me why people who have never-met me hate me,” he pleaded. “Tell me why people who don’t even know what I stand for send me letters demanding I emigrate to Russia. Tell me why facts are so distorted that Arthur Scargill is accused of running this country down. I’d be kidding if I said the hate didn’t hurt.”

Arthur Scargill raised both arms as though nailed to a cross. “Tell me why people who have never-met me hate me,” he pleaded. “Tell me why people who don’t even know what I stand for send me letters demanding I emigrate to Russia. Tell me why facts are so distorted that Arthur Scargill is accused of running this country down. I’d be kidding if I said the hate didn’t hurt.”

Then he dropped his arms and grinned broadly: “But they still love me round here.”

King Arthur was sitting behind the desk in his large, comfortable office in Barnsley. He is right about the love. He delights in telling how his miners call the £10 notes in their wage packets “Arthur Scargills”.

He represents thousands of disabled miners, and has fought hard for their injury compensation. He is proud of the skills and productivity of miners and never stops battling to improve their quality of life

Such pride and closeness is understandable because until 1972 Arthur Scargill was crawling along two feet high tunnels, choking on coal dust and using sign language to communicate above the machinery noise. He was born forty three years ago in a one-up, one-down cottage with no electricity, hot water or an inside lavatory.

At seventeen, he went underground. A year later his mother died, and it was a shock he never forgot – the pain still shows when he speaks of her. “I was an only child and we had a lovely warm relationship. She did all her own baking and I didn’t eat a slice of shop-bought bread until she died.”

The strength of his commitment to his family and to his men can be explained by the close, almost tribal, society of Yorkshire mining villages. A shared background of poverty and danger has produced communities whose support for each other is equalled only by their disdain for Coal Board bosses, Tories and a public which complains about “greedy miners.”

“There is only one place I want to live and that’s Yorkshire”, he said. “My roots are here, my friends are here.”

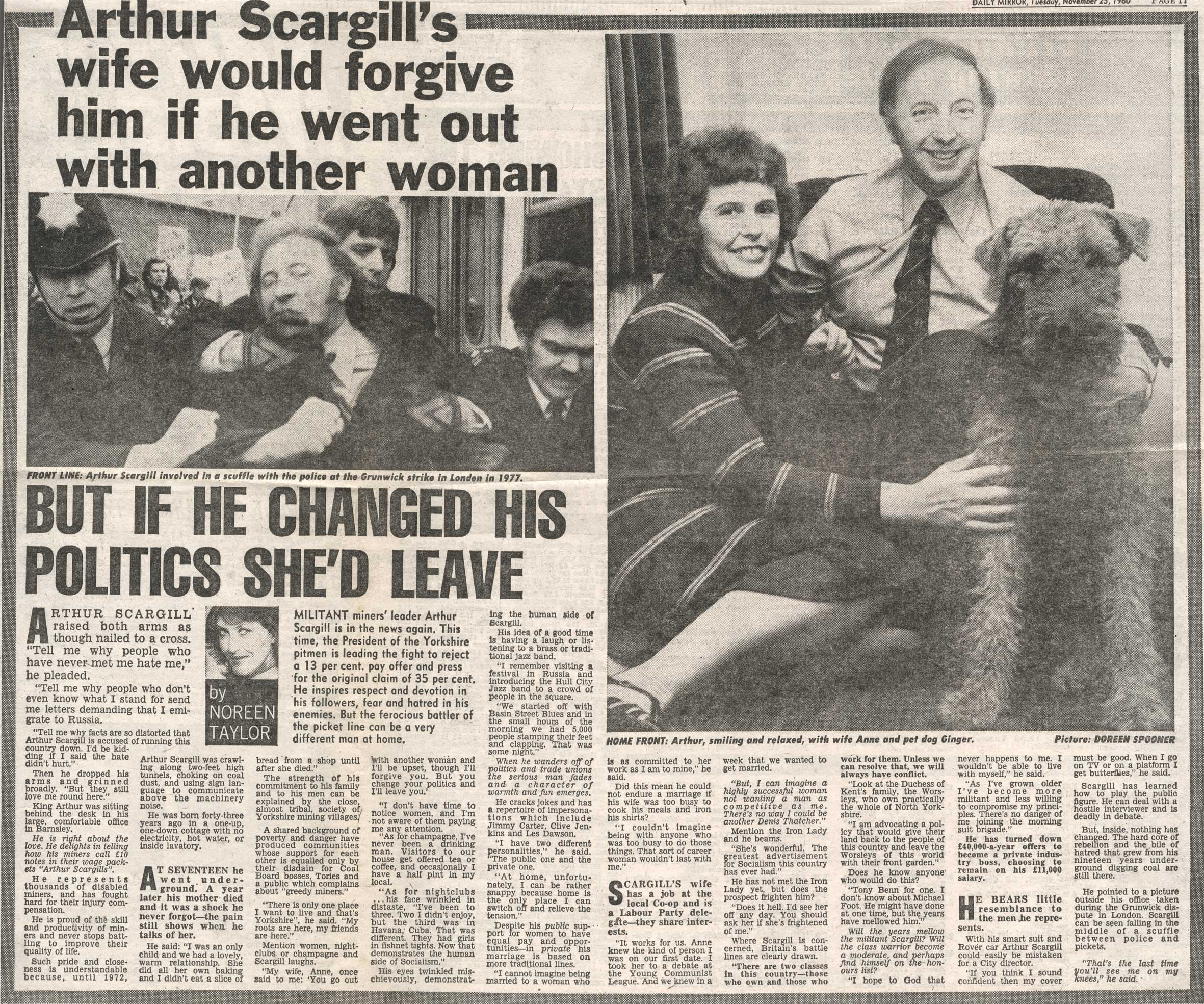

Mention women, nightclubs or champagne and Scargill laughs. “My wife, Anne, once said to me, ‘You go out with another woman and I’ll be upset, though I’ll forgive you. But you change your politics and I’ll leave you.’

“I don’t have time to notice women, and I’m not aware of them paying me any attention. As for champagne I have never been a drinking man. Visitors to our house get offered tea of coffee, and occasionally I might have a half pint in my local.

“As for nightclubs, his face wrinkled in distaste, I’ve been to three. Two I didn’t enjoy, but the third was in Havana, Cuba where they had girls in fish net tights. Now that demonstrates the human side of socialism.”

His eyes twinkled mischievously, demonstrating the human side of Scargill. His idea of having a good time is having a laugh or listening to a brass or traditional Jazz band.

“I remember visiting a festival in Russia and introducing the Hull City Jazz band to a crowd of people in the square.

“We started off with Basin Street Blues and in the small hours of the morning we had 5,000 people stamping their feet and clapping. That was some night.”

When he wanders off of politics and trade unions the serious man fades and a character of warmth and fun emerges. He cracks jokes and has a repertoire of impersonations which include Jimmy Carter, Clive Jenkins and Les Dawson.

“I have two different personalities,” he said. “The public one and the private one. At home, unfortunately, I can be rather snappy because home is the only place I can switch off and relieve the tension.”

Despite his public support for women to have equal pay and opportunities – in private, his marriage is based along more traditional lines.“I cannot imagine being married to a woman who is as committed to her work as I am to mine,” he said.

Did this mean he could not endure a marriage if his wife was too busy to cook his meals and iron his shirts? “I couldn’t imagine being with anyone who was too busy to do those things. That sort of career woman wouldn’t last with me.”

Scargill’s wife has a job at the local co-op and is a Labour Party delegate – they share interests. “It works for us. Anne knew the kind of person I was on our first date when I took her to a debate at the Young Communist League. We knew within a week we wanted to get married. But I can imagine a highly successful woman not wanting a man as competitive as me. There’s no way I could be another Denis Thatcher.”

Mention the Iron Lady and he beams. “She’s wonderful. The greatest advertisement for socialism this country has ever had.” He has not met the Iron Lady yet, but does the prospect frighten him? “Does it hell. I’d see her off any day. You should ask her if she’s frightened of me.”

Where Scargill is concerned, Britain’s battle lines are clearly drawn. “There are two classes in this country – those who own and those who work for them. Unless we can resolve that, we will always have conflict.

“Look at the Duchess of Kent’s family, the Worsleys, who own practically the whole of North Yorkshire. I am advocating a policy that would give their land back to the people of this country and leave the Worsleys of this world with their front garden.”

Does he know anyone who would do this? “Tony Benn for one. I don’t know about Michael Foot, he might have done at one time, but the years have mellowed him.”

Will the years mellow the militant Scargill? Will the class warrior become a moderate and perhaps find himself on the honours list?

“I hope to God than ever happens to me. I wouldn’t be able to live with myself,” he said. “As I’ve grown older I’ve become more militant and less willing to compromise my principles. There’s no danger of me joining the morning suit brigade.”

He has turned down £40,000-a-year offers to become a private industry boss, choosing to remain on his £11,000 salary. He bears little resemblance to the men he represents.

With his smart suit and Rover car Arthur could be easily be mistaken for a City director. “If you think I sound confident then my cover must be good. When I go on TV or on a platform I get butterflies,” he said.

Scargill has learned how to play the public figure. He can deal with a hostile interviewer and is deadly in debate. But, inside, nothing has changed. The hard core of rebellion and the bile of hatred that grew from his nineteen years digging underground are still there.

He pointed to a picture outside his office taken during the Grunwick dispute in London. Scargill can be seen falling in the middle of a scuffle between police and pickets.“That’s the last time you’ll ever see me on my knees,” he said.