Noreen Taylor recalls the time Jacqueline Onassis rescued her from the attentions of Ted Kennedy, and then began to speak . .

PERHAPS IT was fitting that I should have met Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis at a funeral: her life was punctuated by them. It was one of those odd, accidental encounters, all the more strange, given her antipathy towards all journalists and any publicity. .It happened on a train, on a freezing winter’s day, nine years ago. Jackie, along with other members of the Kennedy fami- ly, had travelled to Wales for the funeral of their friend Lord Harlech, the former British ambassador to Washington.

The Kennedys, including Teddy, his sis- ter Jean Smith, and her son Stephen, had hired a private rail carriage for the return journey from Bangor to Euston. I had been covering the funeral for the Daily Mirror and was returning on the main section of the train, near the buffet car.

It was Edward Kennedy’s fondness for bars — he was then an alcoholic — which led to the meeting with Jackie. He recog- nised me from the funeral, though remained unclear about why I had been there, so he stopped on his way past my table. He was clutching a carrier bag full of whisky miniatures, plastic tumblers and ice.

He began by talking of his sadness at the death of David Harlech in a car crash. Then, on the spur of the moment, aware that he was attracting stares from other passengers, he asked if I would like to join the family in their private carriage. Threat- ened by the prospect of six hours on their own in a railway carriage, the Kennedys seemed relieved to have fresh company. Drinks were distributed and Teddy, realising that we shared an Irish back- ground, insisted that time would go faster with a selection of traditional Irish airs.

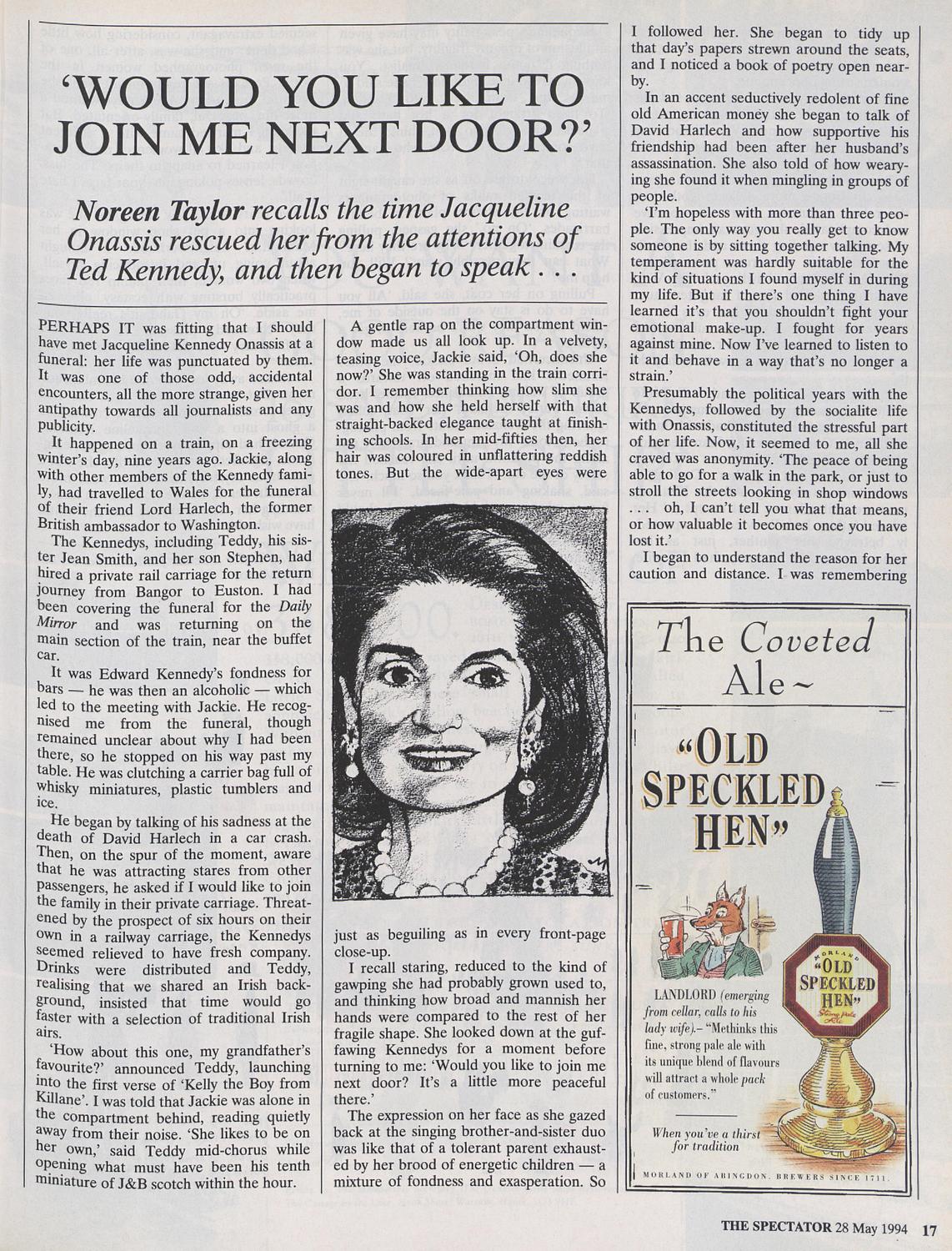

`How about this one, my grandfather’s favourite?’ announced Teddy, launching into the first verse of ‘Kelly the Boy from Killane’. I was told that Jackie was alone in the compartment behind, reading quietly away from their noise. ‘She likes to be on her Own,’ said Teddy mid-chorus while opening what must have been his tenth miniature of J&B scotch within the hour. A gentle rap on the compartment win- dow made us all look up. In a velvety, teasing voice, Jackie said, ‘Oh, does she now?’ She was standing in the train corri- dor. I remember thinking how slim she was and how she held herself with that straight-backed elegance taught at finish- ing schools. In her mid-fifties then, her hair was coloured in unflattering reddish tones. But the wide-apart eyes were just as beguiling as in every front-page close-up. I recall staring, reduced to the kind of gawping she had probably grown used to, and thinking how broad and mannish her hands were compared to the rest of her fragile shape. She looked down at the guf- fawing Kennedys for a moment before turning to me: ‘Would you like to join me next door? It’s a little more peaceful there.’

The expression on her face as she gazed back at the singing brother-and-sister duo was like that of a tolerant parent exhaust- ed by her brood of energetic children — a mixture of fondness and exasperation. So I followed her. She began to tidy up that day’s papers strewn around the seats, and I noticed a book of poetry open near- by.

In an accent seductively redolent of fine old American money she began to talk of David Harlech and how supportive his friendship had been after her husband’s assassination. She also told of how weary- ing she found it when mingling in groups of people.

`I’m hopeless with more than three peo- ple. The only way you really get to know someone is by sitting together talking. My temperament was hardly suitable for the kind of situations I found myself in during my life. But if there’s one thing I have learned it’s that you shouldn’t fight your emotional make-up. I fought for years against mine. Now I’ve learned to listen to it and behave in a way that’s no longer a strain.’

Presumably the political years with the Kennedys, followed by the socialite life with Onassis, constituted the stressful part of her life. Now, it seemed to me, all she craved was anonymity. The peace of being able to go for a walk in the park, or just to stroll the streets looking in shop windows oh, I can’t tell you what that means, or how valuable it becomes once you have lost it.’

I began to understand the reason for her caution and distance. I was remembering some of the descriptions by biographers and journalists, yet those millions of words had not come close to describing the woman sitting opposite me.

There was a sense of loss, of sadness about her, as she sat there staring out of the train window. And it was all too easy to imagine that much of her spirit must have died that day in Dallas.

Temperamentally, she seemed to have been cut from a more delicate cloth than the robust Kennedys. More introspective and complicated, she gave an impression of somehow needing them and the confi- dence of their boisterous personalities. When the Kennedys bawling of ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ and fits of laughter burst through from next door her eyes lit up. She said wistfully, ‘I wish I could be like them. I do so admire their bounciness, their love of life. I don’t know how they do it.

It was as though she had learned to come to terms with these rumbustious rel- atives in the same way she had with Jack’s infidelities. Once, consoling Joan Kennedy after she had learned about one of Teddy’s affairs, Jackie had told her, ‘Darling, it doesn’t mean anything. All the Kennedy men are philanderers. Just accept it.’ Her adored father, Jack Bouvier, had repeated- ly betrayed her mother, just as her father-in-law, Joe Kennedy, had his wife, Rose. Jacqueline’s personality may have given an illusion of dreamy fragility, but she was nothing if not a hardened realist. ‘You know what I’d love right now?’ she said to me as the train drew into London. `To head straight for a hot bath and a neck massage. Do you think they’ll have someone at the Ritz who can do that?’

Her voice drifted off as she caught sight of the massed ranks of photographers waiting on the station platform behind barricades. ‘On no,’ she gasped, pulling the curtains together. ‘Why are they here? What can they possibly want? Will you help me?’

Pulling on her coat, she said, ‘All you have to do is stay on the outside of me, shield me so they won’t be able to get a picture.’

Unconcerned about Jackie, the other Kennedys had marched off towards a group of waiting limousines. Jackie, head down, buried beneath her coat collar, ignoring the frenzied shouts from photog- raphers, took my arm and practically ran along the platform until she reached the safety of the car. ‘Thank you so much,’ she said, shaking and pale-faced, ‘I’ll never forget what you did.’ (Perhaps I should have said the same to her: she had, after all, rescued me from the attentions of Ted Kennedy.) Her gratitude as we kissed goodbye seemed extravagant, considering how little I had done; and she was, after all, one of the most photographed women in the world. Perhaps she really meant what she had told me earlier: ‘I’ve always wanted a quiet life, peaceful, family-orientated. But the men I married came with a different agenda, and like all women of my genera- tion I learned to adapt to theirs. The fuss, crowds, lenses poking into your face; I hate it all.’

Five years later I saw her again. She was looking into a pet shop window in her Manhattan neighbourhood. I thought about going up and introducing myself, when two women, their plump red faces practically bursting with ecstasy, elbowed me aside. ‘Oh my Gand, it’s really you,’ they chorused, pressing so close to her face they were practically touching her nose.

I turned away for a second in embarrass- ment. But when I looked back she had gone, somehow fading into the crowd, like a ghost into a wall. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis had slipped away once again, enig- matic, dignified, secretive. In life, she was a glamorous mystery, making us want more of her. In death, we are no closer to under- standing her. That’s exactly how she would have wished it.

Noreen Taylor is senior feature writer on the Daily Mirror.