Lainey Keogh | The Times | June 1997

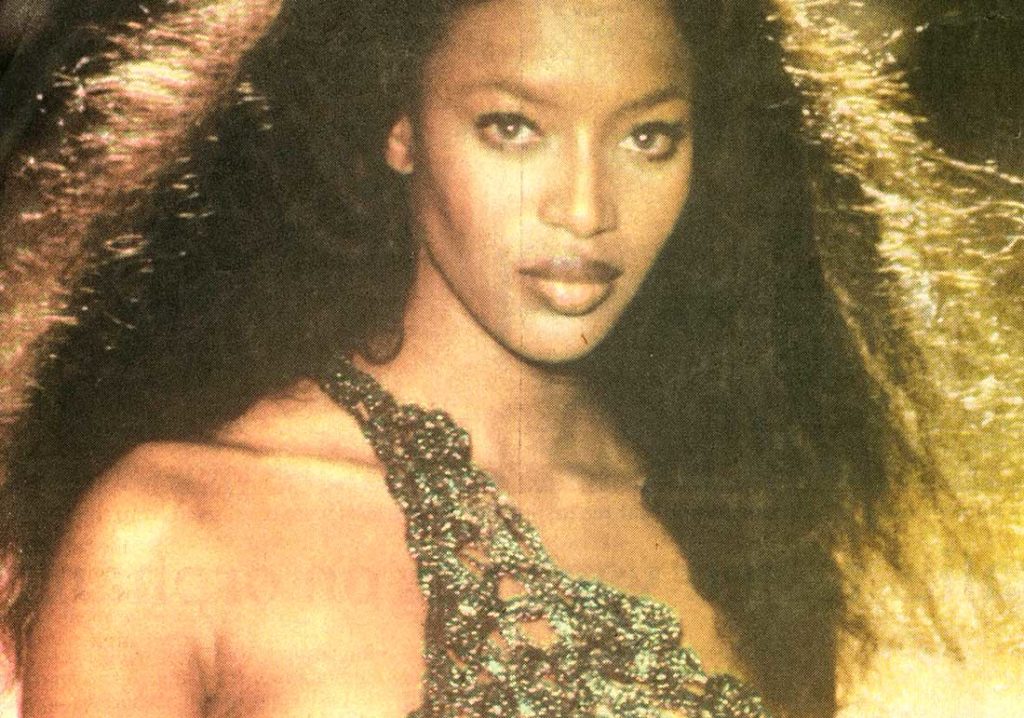

Who did supermodels Naomi, Helena, Honor, Iris and Jodie get out of bed for during London Fashion Week in return for nothing more than a piece of clothing? For someone few of us have even heard of — Lainey Keogh, the Irish knitwear designer and the wealthy woman’s secret.

Who did supermodels Naomi, Helena, Honor, Iris and Jodie get out of bed for during London Fashion Week in return for nothing more than a piece of clothing? For someone few of us have even heard of — Lainey Keogh, the Irish knitwear designer and the wealthy woman’s secret.

“Such lovely girls,” she enthuses back in her Dublin atelier behind buzzing Grafton Street. “And so excited over my clothes. Made me feel great, that appreciation.”

Lainey’s show was staged at the Cobden Club, styled by Isabella Blow. It was the fashion industry’s official recognition of a woman whose business has been thriving for almost ten years. Trophy wives, rock and film stars buy her creations from such exclusive boutiques as Fred Segal in Los Angeles, Joseph in Paris, Luigi of Florence and Browns in London.

“I heard after she died that Jackie Onassis used to buy my sweaters,” says Keogh wistfully. “I wish I’d known so I could have written to her and said, ‘Thank you, you mega-person, for wearing my clothes’. But it’s too late now.”

Few of Lainey’s garments can be bought for under £1,000. And the word “knitted” somehow fails to convey the artistry of her clothes. They are spun from richly coloured silk threads, from cashmere with tints inspired by drifts of mountain smoke, from chenille with pigments so exquisite that they look as if they have been borrowed from the vestments of a Borgia pope.

Lainey has never studied fashion or attended art school. She was brought up on the outskirts of Dublin, one of ten children, and her father ran a market garden. “I’m the product of a great, big, passionate Irish family,” she says proudly.

“My mother knitted Aran sweaters and I used to be fascinated watching as the shapes and patterns grew. They were so intricate, sensual even. Then she taught me, and I used to make all my dolls’ clothes. Yes, I know you would have expected me to have gone to a design college. Instead, at 19, I began studying microbiology, and went on to work in a Dublin hospital lab.

“Disillusion set in about three years later. That coincided with me falling in love for the first time. I made him the most beautiful sweater, layered with suede and leather strips. I gave it to him, he wore it, and then he went off and married someone else.”

The man she loved produced records for U2, and the sweater he wore quickly became the most coveted garment in Dublin rock circles. Marianne Faithfull ordered one to wear on a cover album. The singer Enya bought one. Michael Mortell, the Irish designer, commissioned one for his collection. “People were enchanted and very supportive,” says Lainey. “I was always being invited to things, introduced to people. Eventually, I taught others who became part of my knitting team.”

She is pale-skinned, with tousled, auburn curls and defiant blue eyes, and her figure, encased in one of her own chenille dresses, is comfortably curved. She projects a blend of seen-it-all cynicism rather than the usual bouncy kind of joy associated with fresh success. My request to know her age is brushed aside: “That doesn’t matter.”

I suspect she’s in her mid-thirties. “I have no home,” she says, “no husband, no children. I have lovers though, and my wonderful team of seven in the office, which is what you see here.” What you see is an Aladdin’s cave, stacked full of her next winter collection. The man who got away may have broken her heart, but keeping her head has won her a coveted place the fashion industry

Perfect timing, too. During the late Eighties, a newly confident Ireland emerged. Gifted young people found they could stay at home, write their books, plays and songs. Film-makers, attracted by talent, beautiful unspoilt landscapes and a Government which provided tax breaks, began swarming across Dublin. So many productions were going on at one time that the place became known as Belle Eire.

Costume designers who had become friends began commissioning her to do pieces for various films, and finally an Irish-American businessman introduced her to Barneys, the New York store. “I turned down three meetings with him after I’d found his business was called Top of the Morning. Eventually, I resigned myself and found that he really had an impressive reputation in the American market.”

Various other exclusive boutiques stretching from Palm Beach to San Francisco followed and soon Lainey was on the backs of those who could afford quilted cashmere coats: Liz Taylor, Demi Moore, the Stones, Jack Nicholson and Whoopi Goldberg. “The prices were no obstacle. Each garment is hand-made, and if they can afford them, people don’t mind buying something they see as a work of art,” says Keogh.

“The Americans took everything. Their mouths just dropped open when I opened my suitcases and showed them what I’d made.” The fibres come from Italy but the clothes are made in Ireland. “I love being able to have those words — Made inIreland— on my label. I’m very aware that I’m privileged being able to operate in my own spot.

“I fear I’m beginning to make this journey of mine sound as though it was one quick bound up the stairway to success, because it wasn’t.

About eight years ago, I woke up to find myself under a mountain of debt. I was a naive enthusiast, hobbling along, not bothering with accounts or charging proper rates. When people saw how much I owed, they urged to me to get out, declare myself a bankrupt, to just forget everything and hide away somewhere.

“How could I do that? Knitting was my life. And what about my family’s good name? So I forced myself to stick at it, to learn about profit margins, accounts, credit loans. By July 1992,1 had paid off my debts and was ready to take the next step.”

Now she has 15 hand-knitters working from home who take about a month to make a sweater. “The mass market doesn’t excite me. I enjoy the slow, complicated process that goes into creating each piece. The kind of clothes I want to design will always be individually crafted pieces, and as such cannot be made cheaply. I like to design for women of all sizes — confident, sexy women who are comfortable with their body shape.”

Women with money obviously? “My clothes are like an investment,” comes the dismissive reply. “They invite desire.” Pulling extravagantly lavish cashmere coats from rails to illustrate her point, she strokes the fabric with all the sensuality and affection usually reserved for lovers or babies, crooning their praises.

“Look at this dress! Iris Palmer wore it and looked divine,” she says.

“There were risks on every step of this journey, but they were worth it. Men disappoint, babies grow up and leave you. You’d be right in thinking that clothes are both my pleasure and my reward.”