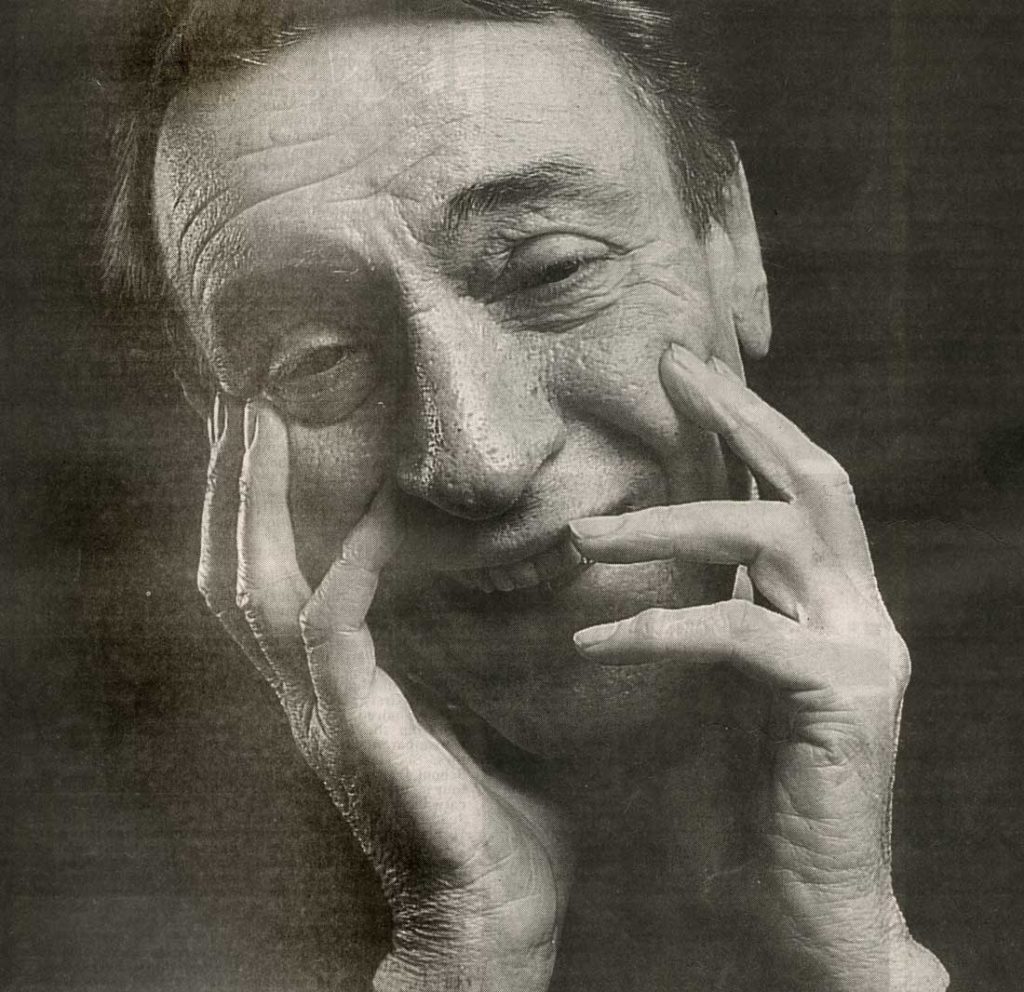

Robert Stephens | The Times | March 1995

There was no mistaking the robust theatrical tones ringing out from the isolation ward in Hampstead’s Royal Free Hospital. Such command in that voice. You could tell it was him. You could almost hear it from reception 10 floors below.

There was no mistaking the robust theatrical tones ringing out from the isolation ward in Hampstead’s Royal Free Hospital. Such command in that voice. You could tell it was him. You could almost hear it from reception 10 floors below.

“Take them all to the bloody Ivy… you must be joking. Too damnably boring for words… And then I said to him, well if you must… but keep the zipper up.”

A bustle of giggling nurses, followed by the immaculately suited figure of Robert Stephens appeared at the ward doorway. Tomorrow he is due to be knighted at Buckingham Palace, a fitting tribute to his late resurgence as one of our finest classical actors.

But, on the day we met, Stephens was still a prisoner of the health system. I had been told that going to interview him would mean donning a plastic apron and gloves, and sister wasn’t too happy about the tape recorder. Stephens wasn’t happy either.

“Can’t stick it in there, and we can’t possibly talk since the room is full of people.” I suggested the hospital restaurant. “No, no. We are getting out of here. Just follow me.”

Down the corridor, into the lift, out of the hospital, along the road and into a local pub. “Half of Beamish, please,” he said, lighting a Camel. “Ought to give me a contract for smoking these. Larry had one for that Olivier brand. Please stop worrying. There is no question of you being charged with kidnapping, or aiding and abetting an escaped patient. I do this all the time. Anyway, I’m only in for a quick check-up because of the old liver and kidney transplant last October.”

We found a private corner, although I’m sure he would have preferred the whole pub to listen in. Then he trotted out a bewildering array of anecdotes, everyone fresh, and with impeccable timing. “You’ll strike out the name, won’t you,’’ he said of one acclaimed knight.

“He was never an alcoholic, dear, merely a bore.” Of another, he said: “Talk about promiscuity. Did it with everyone and was, I learnt years later, hopeless in bed.”

Stephens is 64 and has the cerebral bounce and vivacity of a 20- year-old. However, one could not ignore the frailty of the pale wrist flaying the air, as he embellished another tale, this one involving the timbre of Tiggy Legge-Bourke’s powerful voice.

Tiggy is the assistant in the Prince of Wales’s office and occasional nanny to Princes William and Harry, and Stephens is a familiar figure in royal quarters. Recently, Prince Charles agreed to play Prince Hal in a recording of Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 1. Stephens is compiling a collection of the Bard’s speeches and sonnets, some of which will be set to music if Elton John agrees to take part. The Prince’s Choice will be released next Christmas and profits will go to charity.

“A most beguiling man, Prince Charles, most beguiling,” insisted Stephens. But how can he be so sure that the Prince can hack it? “Of course he can do it. He’s playing a Prince of Wales and he is the Prince of Wales. He is a sensitive, intelligent man, and he played Macbeth at school. He’ll be all right. Anyway, I’ll go through it with him, so he’ll get all the support he needs.”

Both the knight and the Prince are members of a mutual admiration society. “I remember sitting round the table after dinner one night at Sandringham. John Wells had read something, and the Prince asked me if I would. Naturally, I said I’d be happy to. Then I asked if he would like to read.

“So he suggested the entry in his diary from the day of his investiture as the Prince of Wales. It was incredible. Every moment of the day, even to the colour of his mother’s outfit had been recorded in detail. I was amazed at how beautifully he wrote and read. He records faithfully, and in the same detail, all the memorable days in his life, one of which was his first visit to the circus with his grandmother.”

Garrulous, flirtatious, funny, he admits he is at his best in a crowd, preferably at the centre. “No one to talk to in the wards. Don’t really have to be there. I mean, they could have done all the check-ups without me coming in, but I said I didn’t mind. The new liver and kidneys have taken 20 years off my age.”

Robert Stephens was born in Bristol to a mother who charred and a father who worked his way up from labourer to quantity surveyor. “I left home at 15, and rarely went back.”

When he was 17, his mother told him she had tried to abort him with a crochet hook. “Can’t think why she decided to tell me that. Guilt, I suppose.” As a child, he impersonated John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart, and ended up getting a grant to join the Northern Theatrical School. “My father wanted me to be a plumber or a paper hanger.”

Were his parents proud of him? “Oh, yes, of course. ‘Look, our Bobby is in the paper again’. They liked all that. But after she’d seen me doing something, my mother only ever said, ‘that was very nice, dear,’ and I wanted to say, ‘no it wasn’t, it was bloody brilliant.’”

They were never that close; his mother once beat him so badly that she broke a stick over his back. His adult life has provided its own source of drama. There have been four marriages. The first, to Nora Simmonds, lasted three years (“I was on tour for most of it”) and produced a son he has not seen in ages. The next was to actress Tarn Bassett. They had a daughter, Lucy, now a lawyer and very much part of his life.

The third ended in 1975, but so many of his sentences still begin with the words: “Maggie says”. Is this because his eight-year marriage to the actress Maggie Smith signalled one of the most important crossroads in his life?

They were the golden ones of their time, blessed or cursed with a relationship described as one of the most volcanic, sexual chemistries in the business.

“When we broke up, I was plunged into depression and melancholia. For nine months, I suffered a sense of failure. You see, we had been together 24 hours a day. We were doing Noel Coward’s Private Livesin the evenings. It got too much and she asked me one night, just before we went on, to move out because she couldn’t stand living with me anymore.”

He had also made the mistake of confessing that he had been unfaithful, and Maggie vowed she would never forgive him. The infidelities, had she but known, were numerous. “Yes, well, you see I’m a romantic, and they were never one-shot meetings,” he said lamely.

“I adore her, you know,” he added suddenly. “She is wonderful, so talented, so full of variety. I’ve begged her to do Antony and Cleopatra with me, but she won’t.”

This is volunteered, not with the idea that his life is sodden with regret, but to convey that the war between them is over. The failed marriage to Maggie, who moved to Canada, deprived him for eight years of their sons – Toby and Christopher – and of his motivation. For a while he lurked in the shadows, or more prosaically in a basement flat.

He began to drink and his good looks coarsened. “I wasn’t an alcoholic. Just an habitual drinker. I simply liked to drink with my friends. There was no waking up pouring gin over the corn flakes. If you’d met me then, you’d never have known.”

Twenty-five years ago, he was a golden boy, being hailed as the National Theatre’s natural heir to Laurence Olivier; a prophesy never quite fulfilled. He fell out with Olivier, and was cast into the wilderness of overseas tours, bit parts in films and television roles unworthy of his talent. His triumphant return to star billing came through the perceptive young director, Adrian Noble, who cast him as Falstaff in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 1991-2 productions of Henry IV, parts one and two. His performance was deemed definitive and he was awarded the Best Actor of the Year in the 1992 Olivier Awards.

A year later, critics described his King Lear as unforgettable. It earned him the 1993 Globe Award as Best Shakespearean Actor and last month’s Royal Variety Club award for Best Actor. He still enjoys his wine and stout, but these days only in moderation.

“The transplant had nothing to do with me drinking too much. Bloody American clinic giving me a transfusion of dodgy blood; that’s what started the business off.”

His thoughts now are on the future. The latest project is the play, Born Yesterday, the celebrated Fifties film starring Broderick Crawford and Julie Holiday, in which he will co-star with his wife Patricia Quinn.

The couple married only two months ago after 18 years together. Theirs has proved to be the most successful of all his relationships. But they are looking forward to spats on stage. Born Yesterdayis the story of a gangster’s moll who gets educated through the classy wimp her rich gangster boyfriend hires to make her more presentable.

The moll falls for the wimp, and dumps the gangster. In one scene the gangster lashes out, slapping the moll across the face. Will The man who had learnt his craft alongside Redgrave, Richardson and Coward attack Patricia with the same gusto?

“Most certainly,” he says. “She walloped me once across the face in a restaurant. You see, that’s why Pat and I are so wonderful together. She is Irish and bears no grudges. It’s simply wallop, walkout, then it’s all over. And you forget it. It’s very therapeutic. No simmering like it was with Maggie.”

As he wandered back to the isolation ward, he was already planning the evening escape. “There must be a decent Chinese nearby.” We linked arms, and immediately he was back in raconteur mode.

“D’you know what Schwarzenegger said to me, ‘So you act in Shakespearean plays. Me, I do films for morons. Heh, heh, heh. I met Cary Grant once and I insisted we talk only in Bristol accents. We had such a giggle.”

But then Stephens turns everything into a giggle. He is one of those rare creatures you leave feeling happier. And tomorrow he’ll be beaming his sunshine at the investiture lunch which will double as a late wedding celebration.