Gitta Sereny | The Times | 2 May, 1998

Gitta Sereny defends her book about Mary Bell, and tells Noreen Taylor that only good can come out of her decision to confront her past.

Gitta Sereny defends her book about Mary Bell, and tells Noreen Taylor that only good can come out of her decision to confront her past.

As though speaking of a beloved granddaughter, Gitta Sereny says: “I’m worried that Mary may no longer trust me because of what’s happened. But she needs to trust me now more than ever. She needs to know she will always be able to rely on me for love and affection.”

The author is talking after the week’s tidal wave of publicity which has swept the name Mary Bell back into the headlines for killings she committed 30 years ago.

Despite the rancorous public debate, Sereny’s confidence in the moral validity of her book, Cries Unheard, remains unshaken. Yet the whole point of her project has been stood on its head. She sought to offer reason, to help us understand why, to provide a dispassionate documentary. Instead, the book has generated the kind of emotion which would appear to have negated the whole exercise.

Sereny nods in agreement. “Yes. Mary is being called a child killer. But she was a child who killed. Children don’t kill unless something terrible has happened. They aren’t evil people. But now you have respectable newspapers, as well as the tabloids, saying ‘child killer’ and that’s very worrying.” Firing on the nervous energy triggered by the controversy surrounding her book, Sereny is obviously concerned by the mounting hysteria.

Mary Bell is once again a term of abuse. Despite a court order safeguarding her identity, her house was besieged by journalists, and police decided to take her into protective custody, with her 14-year-old daughter. Sereny says: “This little family is marooned, ruined. I don’t know what I can do for them. It’s just barbaric.”

As far as Sereny was concerned, the book would have been launched – noted on news pages and television bulletins. She might have been criticised, applauded, asked for comments – but never in her wildest nightmares could she have imagined the stampede of condemnation and fury that resulted in Bell and her daughter being driven away from their home, hidden under blankets.

Serena had been confident that Mary Bell would not be exposed. Even a journalist of her experience could not have anticipated the savagery of the tabloid pack. Until this week, Bell’s daughter had not been told of her mother’s true identity. “Mary wanted to protect her daughter from her past. I argued with her, told her she was being naive. I warned her that with the publication of the book, the child would inevitably find out. She didn’t want her daughter to become ‘the child of Mary Bell’. I can’t imagine how Mary is dealing with this situation. You see, apart from her partner ‘Jim’, she has no one she can trust.”

A small woman with a large face redolent of an old priest – wise and unshockable – Sereny, now 74, sits over tea at her book-lined West London flat. Her face is shadowed with concern.

“Mary is one ofthe loneliest people I know, and when it becomes too much for her she takes herself off for long walks, far away from her house, going into some tea room and striking up conversation with a stranger, someone at the next table she knows she won’t bump into locally.

“Mary has never been able to have close friends – too dangerous, too much at risk. Consequently, she has built up a core of extraordinary strength to hide her history. Hers is the most incredible double life. I can’t think how she would have coped without ‘Jim’. Now, this week, the poor man has had to watch while a rabble of tabloid journalists invaded his workplace.”

Many newspapers have been critical of Sereny, despite her impeccable pedigree as a writer, for paying Bell. What then does she say to those parents of Bell’s victims who are implacably opposed to Bell receiving money?

She says: “I meant to write to those parents in advance, to prepare them so that they wouldn’t hear in a barbaric form. But someone leaked the story, and now those poor families…”

She wrote a letter of apology to June Richardson, mother of Martin Brown, who immediately rejected the apology. Sereny says: “It’s sad that she showed my letter to the papers. I feel she is being manipulated. She probably feels angry at Mary receiving money, but I can do nothing about that. Mary needed money to change her life. Anyway, she was offered enormous sums by some of the very people now screaming for her blood.”

She is at pains to emphasise that the early reports of the money Bell received were incorrect. “Mary hasn’t been paid anything like £50,000. I gave her part of the advance I was paid. How could I not? Since the day she was born she has been used and abused.”

Would Bell have co-operated without money? “Ah, that’s difficult. I’m not sure. But I can tell you that over the years she has been offered a great deal of money, such as £250,000 from Stern magazine. And there isn’t a paper in the country who would not have given her a large cheque in exchange for ghost-writing her story.

“What mustn’t be forgotten is that Mary chose the most difficult route, the courageous one. She knew how desperately difficult it was going to be. Describing her early childhood was deeply distressing, and I lived through it with her, as did Don. (Sereny’s husband of 50 years, the former photographer Don Honeyman.)

“You see, she’d blanked out all these terrible memories…everything. She would say to me, ‘I’m so afraid of remembering what I think happened’.”

For eight to ten gruelling hours a day, for six months, the dark, tortuous story slowly unfolded. “When she began that journey into her early childhood, one littered with the most unspeakable horrors, describing some of the worst examples of child sexual abuse I’ve ever heard, it was as though she was facing up to the truth of her life for the first time.

“The details…” she shudders as she pauses. “I spoke to a child psychiatrist to see if they made sense, and he confirmed that they did. For a few months after the unblocking of those memories she was euphoric but I knew it wouldn’t last. The burden of what had happened was too heavy to disappear for very long. Inevitably, we have to face the fact that she is a frightfully damaged young woman. Not only by her mother, but by the system.”

Although Bell is now 41, the person Sereny describes and talks of so fondly comes across as a misbegotten teenager. “That’s because she is. In so many ways, she’s like a chaotic child. She’s also intelligent, funny, very chatty. She loves chitchat, is terribly curious about people, and on occasion can be very wise and mature.”

Sereny’s fascination with Bell began soon after news of the deaths broke in 1968. Bell, then aged 11, was convicted of strangling Martin Brown, four, and Brian Howe, three, in Scotswood, a deprived area of Newcastle upon Tyne.

She was intrigued by the enigma of an 11-year-old girl described in sensationalist headlines as an evil spirit. To understand Sereny’s compulsion for this kind of story, we have to look back at her own life.

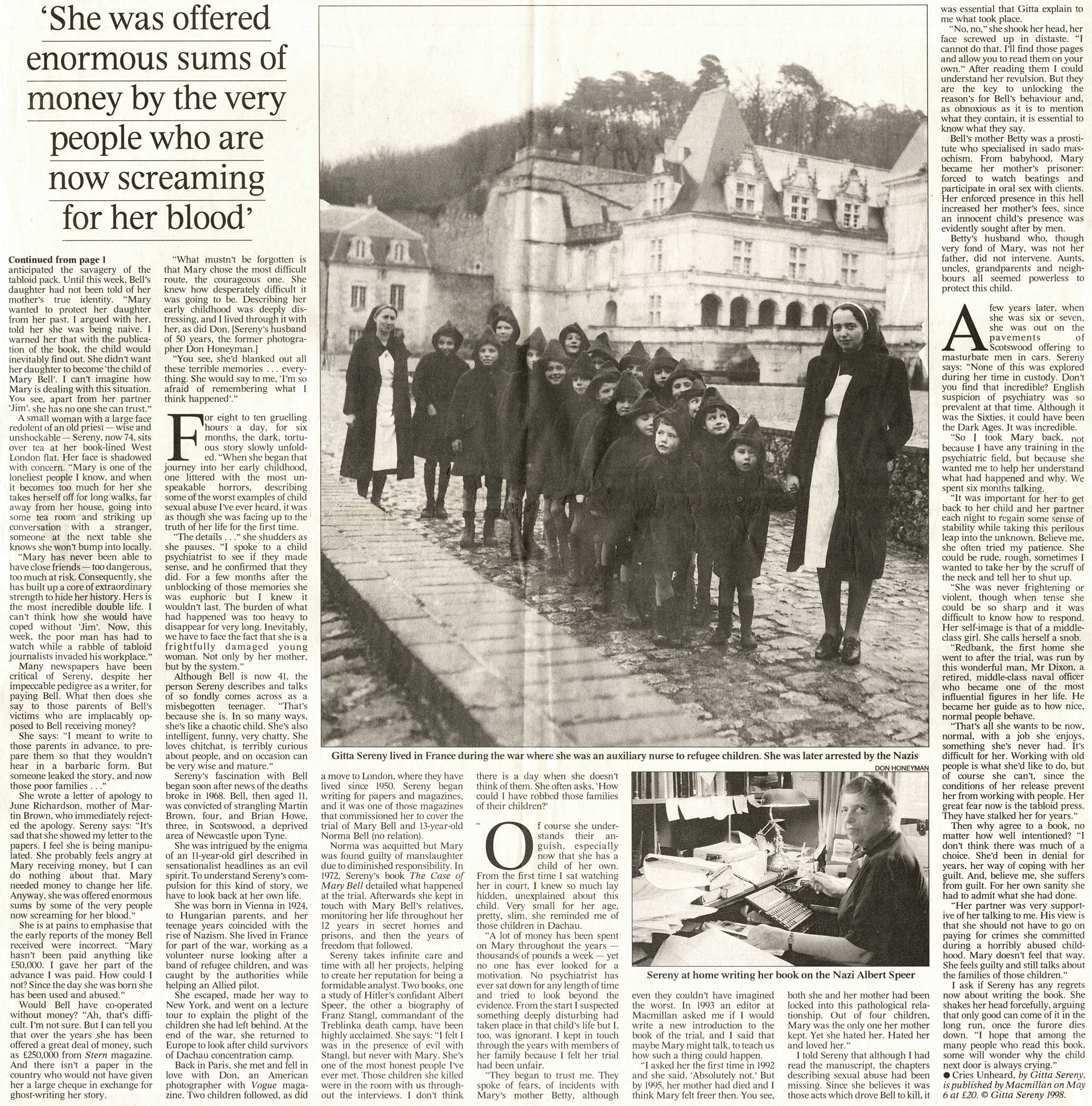

She was born in Vienna in 1924, to Hungarian parents, and her teenage years coincided with the rise of Nazism. She lived in France for part of the war, working as a volunteer nurse looking after a band of refugee children, and was caught by the authorities while helping an Allied pilot.

She escaped, made her way to New York, and went on a lecture tour to explain the plight of the children she had left behind. At the end of the war, she returned to Europe to look after child survivors of Dachau concentration camp.

Back in Paris, she met and fell in love with Don, an American photographer with Vogue magazine. Two children followed, as did a move to London, where they have lived since 1950. Sereny began writing for papers and magazines, and it was one of those magazines that commissioned her to cover the trial of Mary Bell and 13-year-old Norma Bell (no relation).

Norma was acquitted but Mary was found guilty of manslaughter due to diminished responsibility. In 1972, Sereny’s book The Case of Mary Bell detailed what happened at the trial. Afterwards she kept in touch with Mary Bell’s relatives, monitoring her life throughout her 12 years in secret homes and prisons, and then the years of freedom that followed.

Sereny takes infinite care and time with all her projects, helping to create her reputation for being a formidable analyst. Two books, one a study of Hitler’s confidant Albert Speer, the other a biography of Franz Stangl, commandant of the Treblinka death camp, have been highly acclaimed. She says: “I felt I was in the presence of evil with Stangl, but never with Mary. She’s one of the most honest people I’ve ever met. Those children she killed were in the room with us throughout the interviews. I don’t think there is a day when she doesn’t think of them. She often asks, ‘How could I have robbed those families of their children?'”

Of course, she understands their anguish, especially now that she has a child of her own. From the first time I sat watching her in court, I knew so much lay hidden, unexplained about this child. Very small for her age, pretty, slim, she reminded me of those children in Dachau.

“A lot of money has been spent on Mary throughout the years – thousands of pounds a week – yet no one has ever looked for a motivation. No psychiatrist has ever sat down for any length of time and tried to look beyond the evidence. From the start I suspected something deeply disturbing had taken place in that child’s life but I, too, was ignorant. I kept in touch through the years with members of her family because I felt her trial had been unfair.

“They began to trust me. They spoke of fears, of incidents with Mary’s mother Betty, although even they couldn’t have imagined the worst. In 1993 an editor at Macmillan asked me if I would write a new introduction to the book of the trial, and I said that maybe Mary might talk, to teach us how such a thing could happen.

“I asked her the first time in 1992 and she said, ‘Absolutely not.’ But by 1995, her mother had died and I think Mary felt freer then. You see, both she and her mother had been locked into this pathological relationship. Out of four children, Mary was the only one her mother kept. Yet she hated her. Hated her and loved her.”

I told Sereny that although I had read the manuscript, the chapters describing sexual abuse had been missing. Since she believes it was those acts which drove Bell to kill, it was essential that Gitta explain to me what took place.

“No, no,” she shook her head, her face screwed up in distaste. “I cannot do that. I’ll find those pages and allow you to read them on your own.” After reading them I could understand her revulsion. But they are the key to unlocking the reason’ for Bell’s behaviour and, as obnoxious as it is to mention what they contain, it is essential to know what they say.

Bell’s mother Betty was a prostitute who specialised in sadomasochism. From babyhood, Mary became her mother’s prisoner: forced to watch beatings and participate in oral sex with clients. Her enforced presence in this hell increased her mother’s fees, since an innocent child’s presence was evidently sought after by men.

Betty’s husband who, though very fond of Mary, was not her father, did not intervene. Aunts, uncles, grandparents and neighbours all seemed powerless to protect this child.

A few years later, when she was six or seven, she was out on the pavements of Scotswood offering to masturbate men in cars. Sereny says: “None of this was explored during her time in custody. Don’t you find that incredible? English suspicion of psychiatry was so prevalent at that time. Although it was the Sixties, it could have been the Dark Ages. It was incredible.

“So, I took Mary back, not because I have any training in the psychiatric field, but because she wanted me to help her understand what had happened and why. We spent six months talking.

“It was important for her to get back to her child and her partner each night to regain some sense of stability while taking this perilous leap into the unknown. Believe me, she often tried my patience. She could be rude, rough, sometimes I wanted to take her by the scruff of the neck and tell her to shut up.

“She was never frightening or violent, though when tense she could be so sharp and it was difficult to know how to respond. Her self-image is that of a middle-class girl. She calls herself a snob.

“Redbank, the first home she went to after the trial, was run by this wonderful man, Mr Dixon, a retired, middle-class naval officer who became one of the most influential figures in her life. He became her guide as to how nice, normal people behave.

“That’s all she wants to be now, normal, with a job she enjoys, something she’s never had. It’s difficult for her. Working with old people is what she’d like to do, but of course she can’t, since the conditions of her release prevent her from working with people. Her great fear now is the tabloid press. They have stalked her for years.”

Then why agree to a book, no matter how well intentioned? “I don’t think there was much of a choice. She’d been in denial for years, her way of coping with her guilt. And, believe me, she suffers from guilt. For her own sanity she had to admit what she had done.

“Her partner was very supportive of her talking to me. His view is that she should not have to go on paying for crimes she committed during a horribly abused childhood. Mary doesn’t feel that way. She feels guilty and still talks about the families of those children.”

I ask if Sereny has any regrets now about writing the book. She shakes her head forcefully, arguing that only good can come of it in the long run, once the furore dies down. “I hope that among the many people who read this book, some will wonder why the child next door is always crying.”

*Cries Unheard, by Gitta Sereny, is published by Macmillan on May 6.