Beryl Bainbridge | The Times | 24 April, 1998

I was warned in advance about Beryl Bainbridge. Terrific, hugely talented novelist, but totally barking, wildly eccentric, off the wall. And you should see the house. A mess, dear, a fright. So let me immediately put the record straight. I found her charming, wise and very honest. Her critics are, so to speak, barking up the wrong tree.

I was warned in advance about Beryl Bainbridge. Terrific, hugely talented novelist, but totally barking, wildly eccentric, off the wall. And you should see the house. A mess, dear, a fright. So let me immediately put the record straight. I found her charming, wise and very honest. Her critics are, so to speak, barking up the wrong tree.

Eccentric? OK, so the North London terraced house looks like the bargain basement of a 1950s flea market, but that was terribly cutting edge among postwar Bohemians. She just hasn’t changed houses or decor since. Her housemates – a lifesized buffalo behind the front door and the statues of St Patrick, St Teresa and St Antony – can be viewed as early Post-Modern irony.

As for Beryl the writer, she’s hot right now. Every Man For Himself, a recreation of four days on the Titanic before it sank, has become an international bestseller. Endearingly, she says she thinks it is selling because everyone assumes that it is the book of the film.

Now Master Georgie, her eighteenth book, has just been launched. “You’ve read it?”

“Of course I have.”

“How many times?”

“Once.”

“Oh, you have to read it more than once. Most people have to read it at least three times before they understand it.”

The novel is set in the mid-19th century, during the Crimean War. It unfolds through the narratives of three characters whose destinies are linked through a past incident. It is multi-layered, though written in the crisp, stylish prose that has placed Beryl on three Booker shortlists and won her two Whitbread prizes.

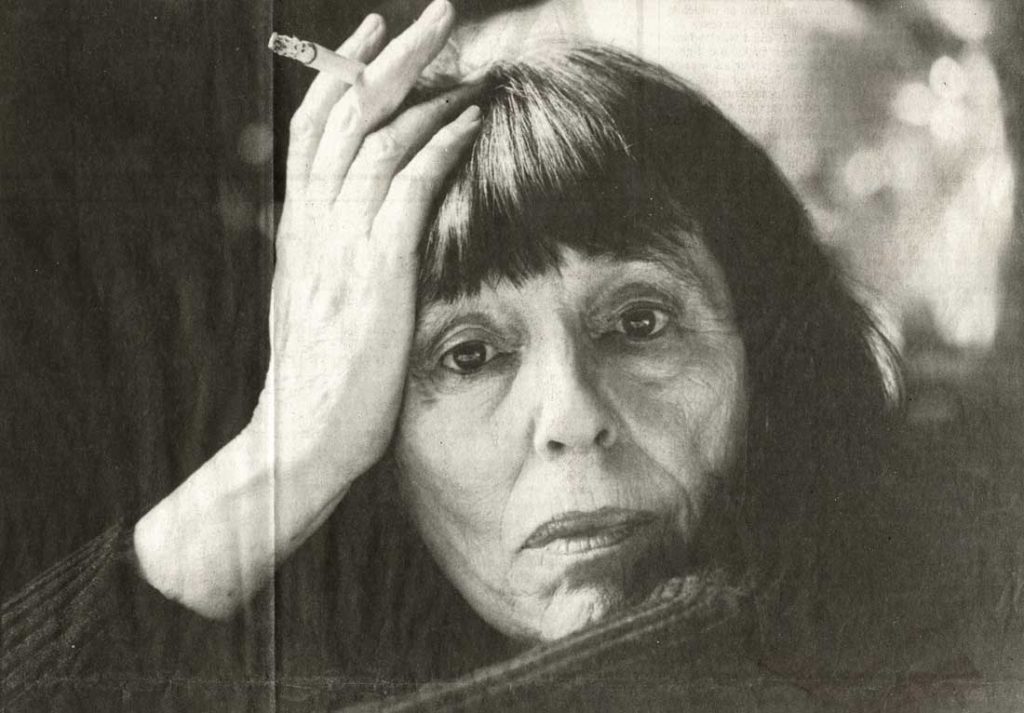

“I’d always written about my life and my background, and then I ran out of ideas. So my publisher offered one of these three-book deals, and asked what I’d like to write about. Off the top of my head, I trotted out Scott of the Antarctic, the Titanic and the Crimea. I have always loved history and anyway I cannot make anything up. I mean why bother when life is so extraordinary,” says Beryl, a slim, neat figure in black, with her black, straight, fringed hairstyle still faithful to some long-ago Beat image, probably Juliette Greco, whom she resembled when young.

She was born in Liverpool in 1934, joined the Liverpool Playhouse as an actress at 16, and four years later married a painter, Austin Davies. They had two children before the marriage ended. Her third child is from a relationship with the writer Alan Sharp.

After years of stretching frugal earnings, hers must be a rather comfortable life. Since her writing career began in 1968, three of her books have been made into films, and sales have finally brought in enough money for her to splash out, to shop and indulge herself.

“I hate money. Think it’s disgusting, which is why I wrote my novel Filthy Lucre. I don’t agree with pensions and investments. All these people pestering me to invest in their banks makes me sick. Give it away, that’s my theory. Every time I have, it has always come back double.

“You see, during those years when my children were young I never actually felt poor. Aussie lived in the basement and gave me £7 a week. You could buy one of those lovely little shift dresses then for £2. Markets round here were wonderful for junk, which is where everything you see in this house came from. I didn’t want for anything.

“On Fridays, if I ran out, I had this arrangement with the woman across the road who would loan me 30 shillings till Monday. If the telephone or electricity were about to be cut off, I’d just write a nice letter, explaining I’d pay them back five shillings a week. It always worked. Mind you, to this day, I don’t eat fruit. Fruit was for the children so I’ve just never bothered.”

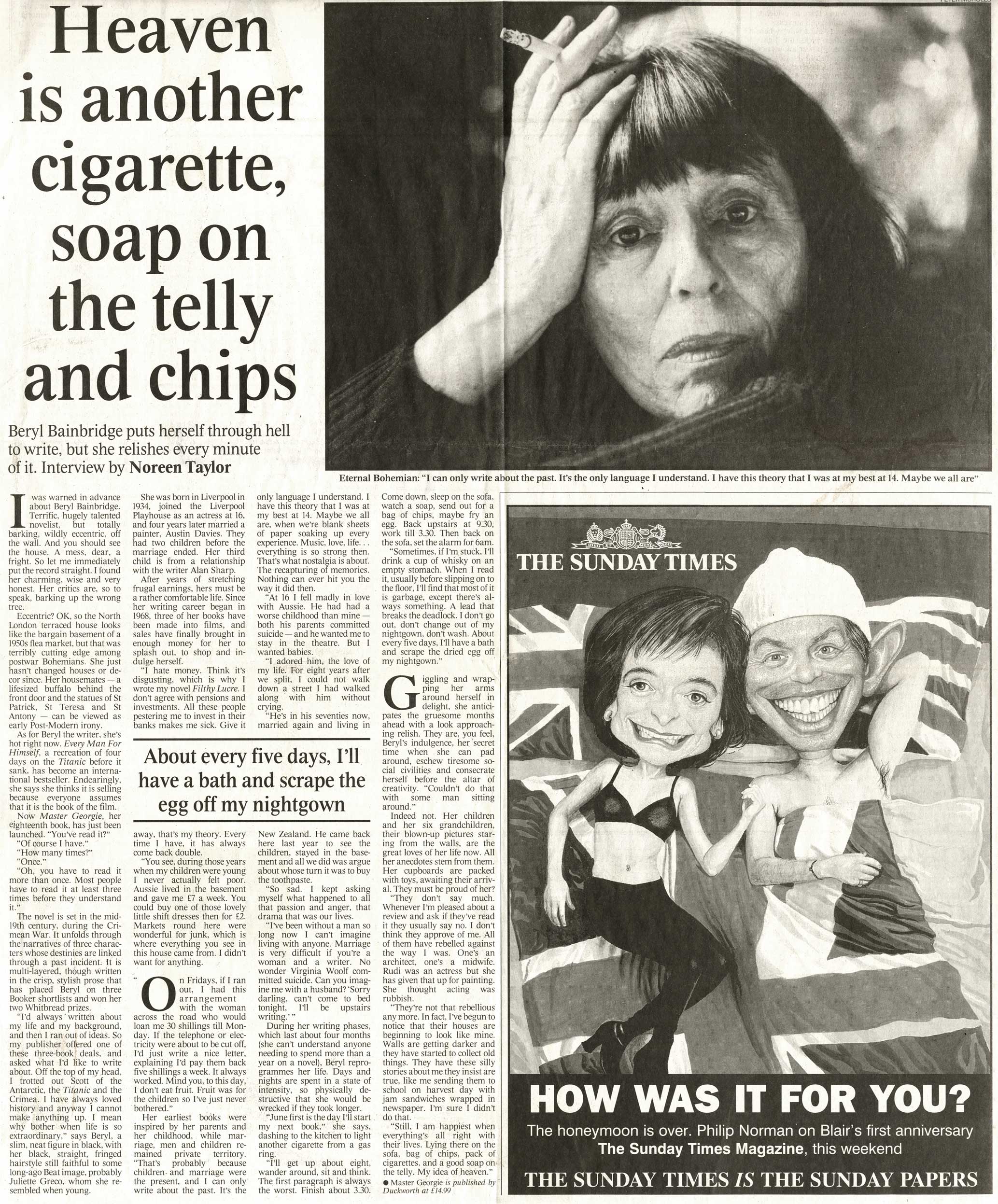

Her earliest books were inspired by her parents and her childhood, while marriage, men and children remained private territory. “That’s probably because children and marriage were the present, and I can only write about the past. It’s the only language I understand. I have this theory that I was at my best at 14. Maybe we all are, when we’re blank sheets of paper soaking up every experience. Music, love, life…everything is so strong then. That’s what nostalgia is about. The recapturing of memories. Nothing can ever hit you the way it did then.

“At 16 I fell madly in love with Aussie. He had had a worse childhood than mine – both his parents committed suicide – and he wanted me to stay in the theatre. But I wanted babies. I adored him, the love of my life. For eight years after we split, I could not walk down a street I had walked along with him without crying.

“He’s in his seventies now, married again and living in New Zealand. He came back here last year to see the children, stayed in the basement and all we did was argue about whose turn it was to buy the toothpaste.

“So sad. I kept asking myself what happened to all that passion and anger, that drama that was our lives. I’ve been without a man so long now I can’t imagine living with anyone. Marriage is very difficult if you’re a woman and a writer. No wonder Virginia Woolf committed suicide. Can you imagine me with a husband? ‘Sorry darling, can’t come to bed tonight, I’ll be upstairs writing.’ “

During her writing phases, which last about four months (she can’t understand anyone needing to spend more than a year on a novel), Beryl re-programmes her life. Days and nights are spent in a state of intensity, so physically destructive that she would be wrecked if they took longer.

“June first is the day I’ll start my next book,” she says, dashing to the kitchen to light another cigarette from a gas ring.

“I’ll get up about eight, wander around, sit and think. The first paragraph is always the worst. Finish about 3.30. Come down, sleep on the sofa, watch a soap, send out for a bag of chips, maybe fry an egg. Back upstairs at 9.30, work till 3.30. Then back on the sofa, set the alarm for 6am.

“Sometimes, if I’m stuck, I’ll drink a cup of whisky on an empty stomach. When I read it, usually before slipping on to the floor, I’ll find that most of it is garbage, except there’s always something. A lead that breaks the deadlock. I don’t go out, don’t change out of my nightgown, don’t wash. About every five days, I’ll have a bath and scrape the dried egg off my nightgown.”

Giggling and wrapping her arms around herself in delight, she anticipates the gruesome months ahead with a look approaching relish. They are, you feel, Beryl’s indulgence, her secret time when she can pad around, eschew tiresome social civilities and consecrate herself before the altar of creativity. “Couldn’t do that with some man sitting around.”

Indeed not. Her children and her six grandchildren, their blown-up pictures staring from the walls, are the great loves of her life now. All her anecdotes stem from them. Her cupboards are packed with toys, awaiting their arrival. They must be proud of her?

“They don’t say much. Whenever I’m pleased about a review and ask if they’ve read it they usually say no. I don’t think they approve of me. All of them have rebelled against the way I was. One’s an architect, one’s a midwife. Rudi was an actress but she has given that up for painting. She thought acting was rubbish.

“They’re not that rebellious any more. In fact, I’ve begun to notice that their houses are beginning to look like mine. Walls are getting darker and they have started to collect old things. They have these silly stories about me they insist are true, like me sending them to school on harvest day with jam sandwiches wrapped in newspaper. I’m sure I didn’t do that.

“Still, I am happiest when everything’s all right with their lives. Lying there on the sofa, bag of chips, pack of cigarettes, and a good soap on the telly. My idea of heaven.”