Angelica Garnett | The Times | June 2001

Her first words, on the phone before our interview, are daunting: “Am I going to have to go over the past with you?” Her wariness is understandable: Angelica Garnett is so defined as a child of Bloomsbury that she has never escaped the curiosity of people who see her as a historical, rather than a topical, figure.

Her first words, on the phone before our interview, are daunting: “Am I going to have to go over the past with you?” Her wariness is understandable: Angelica Garnett is so defined as a child of Bloomsbury that she has never escaped the curiosity of people who see her as a historical, rather than a topical, figure.

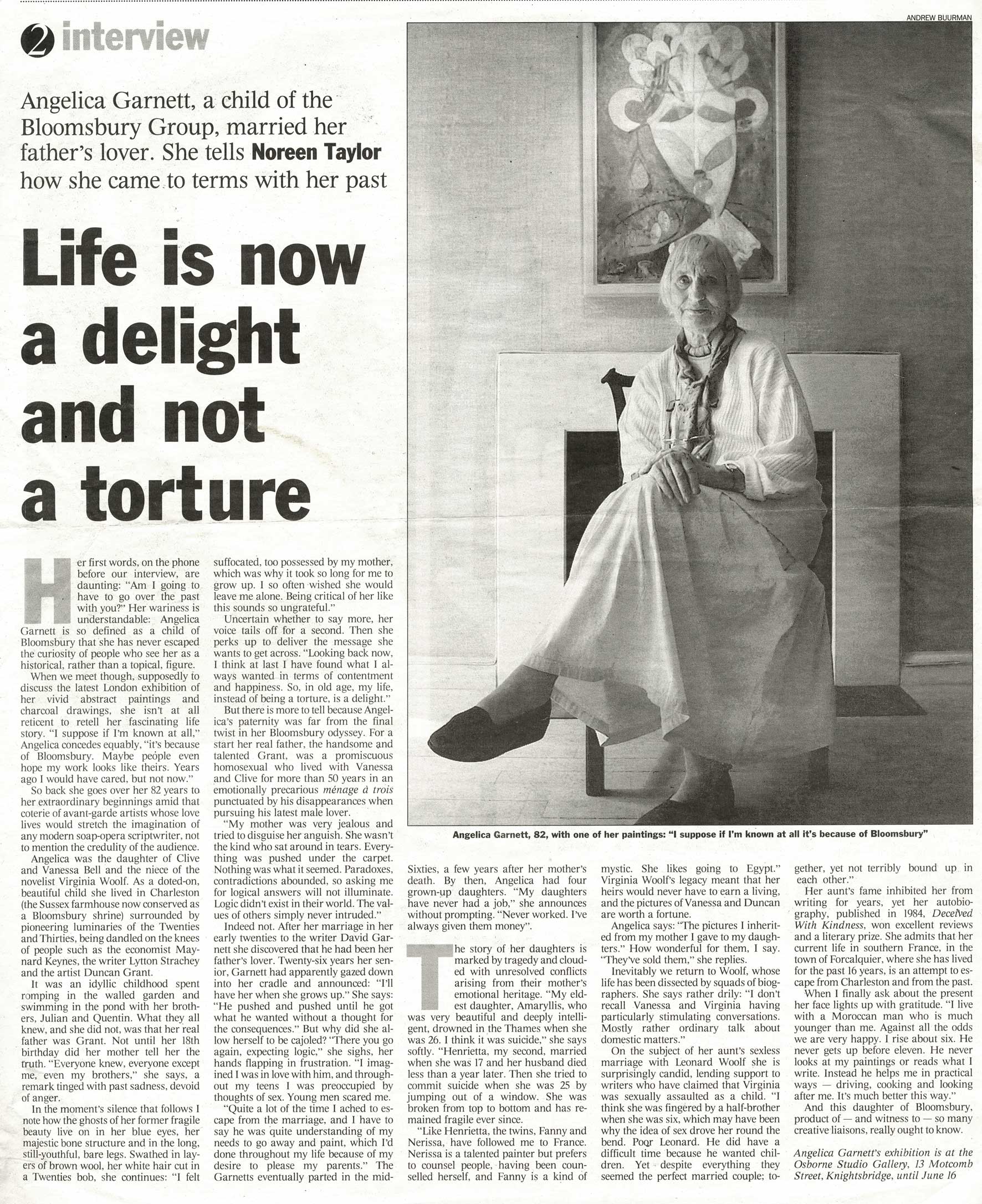

When we meet though, supposedly to discuss the latest London exhibition of her vivid abstract paintings and charcoal drawings, she isn’t at all reticent to retell her fascinating life story.

“1 suppose if I’m known at all,” Angelica concedes equably, “it’s because of Bloomsbury. Maybe people even hope my work looks like theirs. Years ago, I would have cared, but not now.” So, back she goes over her 82 years to her extraordinary beginnings amid that coterie of avant-garde artists whose love lives would stretch the imagination of any modern soap-opera scriptwriter, not to mention the credulity of the audience.

Angelica was the daughter of Clive and Vanessa Bell and the niece of the novelist Virginia Woolf. As a doted-on, beautiful child she lived in Charleston (the Sussex farmhouse now conserved as a Bloomsbury shrine) surrounded by pioneering luminaries of the Twenties and Thirties, being dandled on the knees of people such as the economist Maynard Keynes, the writer Lytton Strachey and the artist Duncan Grant.

It was an idyllic childhood spent romping in the walled garden and swimming in the pond with her brothers, Julian and Quentin. What they all knew, and she did not, was that Duncan Grant was her real father. Not until her 18th birthday did her mother tell her the truth.

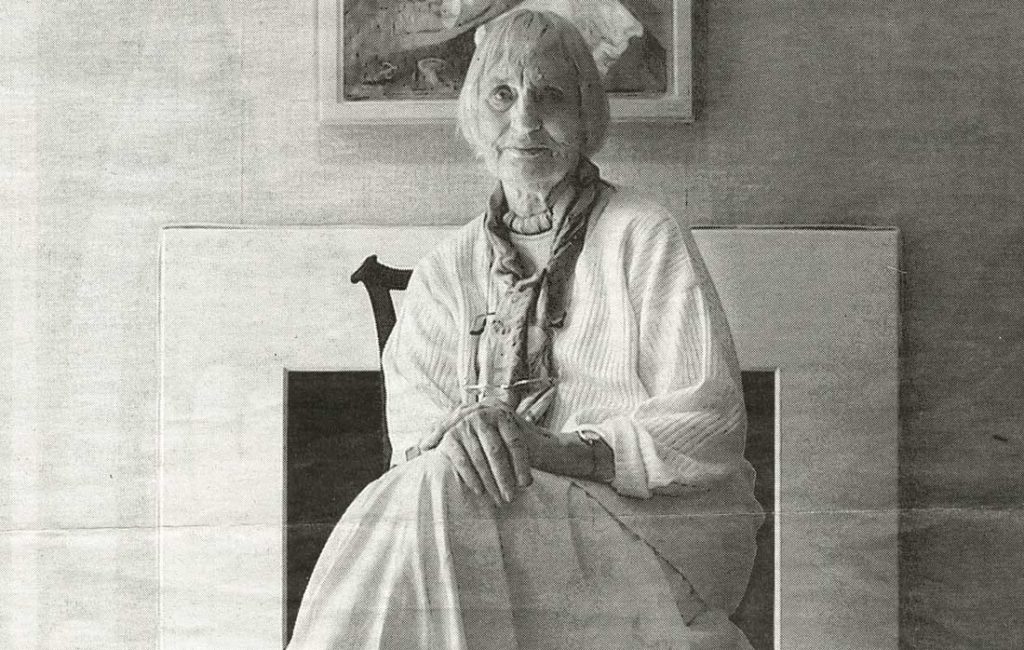

“Everyone knew, everyone except me, even my brothers,” she says, a remark tinged with past sadness, devoid of anger. In the moment’s silence that follows I note how the ghosts of her former fragile beauty live on in her blue eyes, her majestic bone structure and in the long, still-youthful, bare legs.

Swathed in layers of brown wool, her white hair cut in a Twenties bob, she continues: “I felt suffocated, too possessed by my mother, which was why it took so long for me to grow up. I so often wished she would leave me alone. Being critical of her like this sounds so ungrateful.”

Uncertain whether to say more, her voice tails off for a second. Then she perks up to deliver the message she wants to get across. “Looking back now, I think at last I have found what I always wanted in terms of contentment and happiness. So, in old age, my life, instead of being a torture, is a delight.”

But there is more to tell because Angelica’s paternity was far from the final twist in her Bloomsbury odyssey. For a start her real father, the handsome and talented Grant, was a promiscuous homosexual who lived with Vanessa and Clive for more than 50 years in an emotionally precarious menage a troispunctuated by his disappearances when pursuing his latest male lover.

“My mother was very jealous and tried to disguise her anguish. She wasn’t the kind who sat around in tears. Everything was pushed under the carpet. Nothing was what it seemed. Paradoxes, contradictions abounded, so asking me for logical answers will not illuminate. Logic didn’t exist in their world. The values of others simply never intruded.”

Indeed not. After her marriage in her early twenties to the writer David Garnett she discovered that he had been her father’s lover. Twenty-six years her senior, Garnett had apparently gazed down into her cradle and announced: “I’ll have her when she grows up.”

She says: “He pushed and pushed until he got what he wanted without a thought for the consequences.” But why did she allow herself to be cajoled? “There you go again, expecting logic,” she sighs, her hands flapping in frustration.

“I imagined I was in love with him, and throughout my teens I was preoccupied by thoughts of sex. Young men scared me. Quite a lot of the time I ached to escape from the marriage, and I have to say he was quite understanding of my needs to go away and paint, which I’d done throughout my life because of my desire to please my parents.”

The Garnetts eventually parted in the mid Sixties, a few years after her mother’s death. By then, Angelica had four grown-up daughters. “My daughters have never had a job,” she announces without prompting. “Never worked. I’ve always given them money.”

The story of her daughters is marked by tragedy and clouded with unresolved conflicts arising from their mother’s emotional heritage. “My eldest daughter, Amaryllis, who was very beautiful and deeply intelligent, drowned in the Thames when she was 26. I think it was suicide,” she says softly. “Henrietta, my second, married when she was 17 and her husband died less than a year later. Then she tried to commit suicide when she was 25 by jumping out of a window. She was broken from top to bottom and has remained fragile ever since.

“Like Henrietta, the twins, Fanny and Nerissa, have followed me to France. Nerissa is a talented painter but prefers to counsel people, having been counselled herself, and Fanny is a kind of mystic. She likes going to Egypt.”

Virginia Woolf’s legacy meant that her heirs would never have to earn a living, and the pictures of Vanessa and Duncan are worth a fortune. Angelica says: “The pictures I inherited from my mother I gave to my daughters.”

How wonderful for them, I say. “They’ve sold them,” she replies. Inevitably we return to Woolf, whose life has been dissected by squads of biographers. She says rather drily: “I don’t recall Vanessa and Virginia having particularly stimulating conversations. Mostly rather ordinary talk about domestic matters.”

On the subject of her aunt’s sexless marriage with Leonard Woolf she is surprisingly candid, lending support to writers who have claimed that Virginia was sexually assaulted as a child. “I think she was fingered by a half-brother when she was six, which may have been why the idea of sex drove her round the bend. Poor Leonard. He did have a difficult time because he wanted children. Yet despite everything they seemed the perfect married couple: together, yet not terribly bound up in each other.”

Her aunt’s fame inhibited her from writing for years, yet her autobiography, published in 1984, Deceived With Kindness, won excellent reviews and a literary prize. She admits that her current life in southern France, in the town of Forcalquier, where she has lived for the past 16 years, is an attempt to escape from Charleston and from the past.

When I finally ask about the present, her face lights up with gratitude. “I live with a Moroccan man who is much younger than me. Against all the odds we are very happy. I rise about six. He never gets up before eleven.

“He never looks at my paintings or reads what I write. Instead he helps me in practical ways – driving, cooking and looking after me. It’s much better this way.” And this daughter of Bloomsbury, product of, and witness to, so many creative liaisons, really ought to know.