Julie Burchill | The Times | February 1999

Julie Burchill doesn’t do coke no more. She just sounds as if she does. Like a ticker-tape machine gone berserk, words gush out, punctuated by totally inappropriate wild spasms of giggling. Her squeaky babble is accompanied by perpetual hair-tugging, a nervous tic that makes you long to seize her hand and shout “stop”.

Julie Burchill doesn’t do coke no more. She just sounds as if she does. Like a ticker-tape machine gone berserk, words gush out, punctuated by totally inappropriate wild spasms of giggling. Her squeaky babble is accompanied by perpetual hair-tugging, a nervous tic that makes you long to seize her hand and shout “stop”.

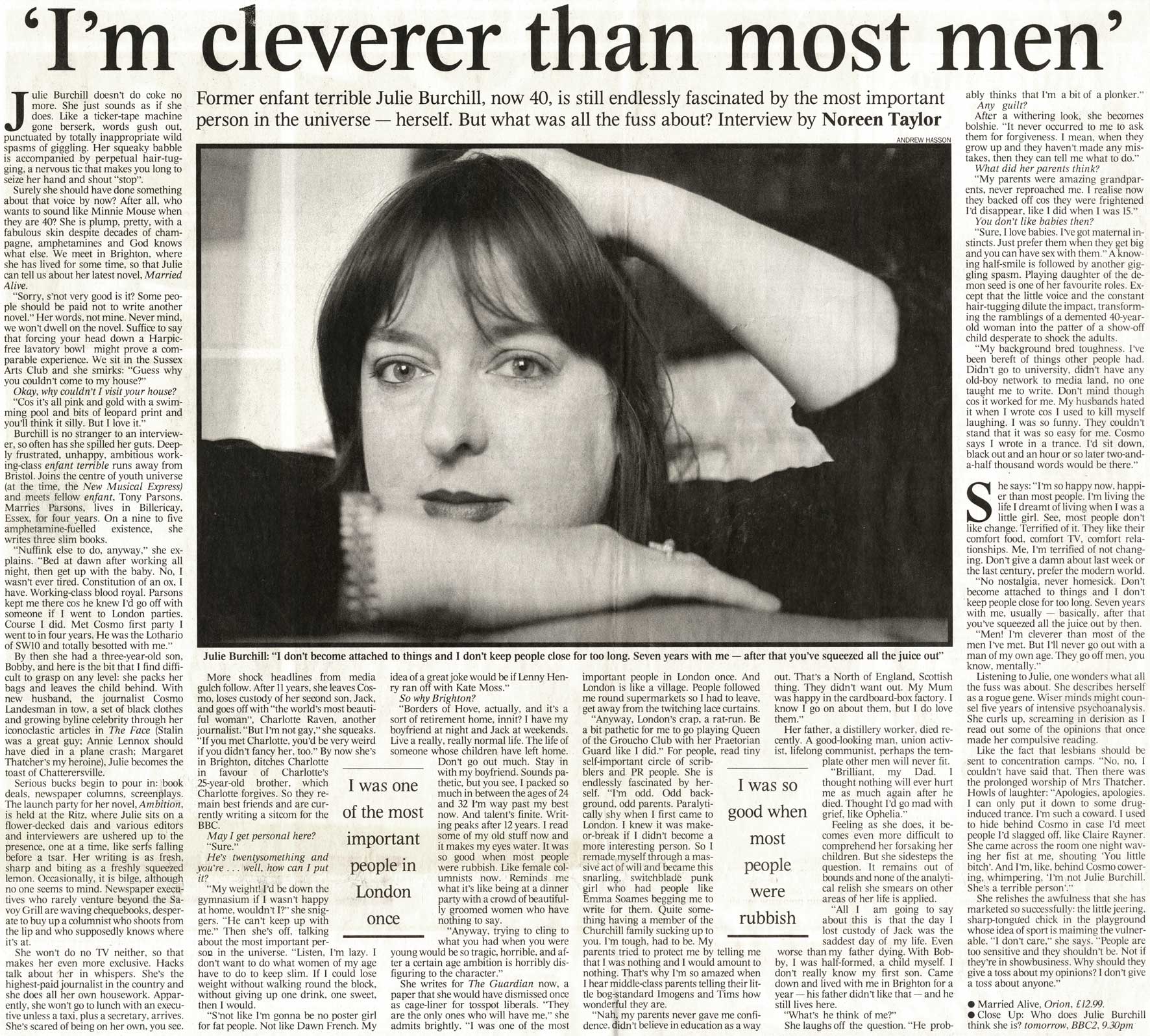

Surely, she should have done something about that voice by now? After all, who wants to sound like Minnie Mouse when they are 40? She is plump, pretty, with a fabulous skin despite decades of champagne, amphetamines and God knows what else. We meet in Brighton, where she has lived for some time, so that Julie can tell us about her latest novel, Married Alive.

“Sorry, s’not very good is it? Some people should be paid not to write another novel.” Her words, not mine. Never mind, we won’t dwell on the novel. Suffice to say that forcing your head down a Harpic free lavatory bowl might prove a comparable experience. We sit in the Sussex Arts Club and she smirks: “Guess why you couldn’t come to my house?”

Okay, why couldn’t I visit your house? “Cos it’s all pink and gold with a swimming pool and bits of leopard print and you’ll think it silly. But I love it.” Burchill is no stranger to an interview, so often has she spilled her guts. Deeply frustrated, unhappy, ambitious working-class enfant terribleruns away from Bristol. Joins the centre of youth universe (at the time, the New Musical Express) and meets fellow enfant, Tony Parsons. Marries Parsons, lives in Billericay, Essex, for four years. On a nine to five amphetamine-fuelled existence, she writes three slim books.

“Nuffink else to do, anyway,” she explains. “Bed at dawn after working all night, then get up with the baby. No, I wasn’t ever tired. Constitution of an ox, I have. Working-class blood royal. Parsons kept me there cos he knew I’d go off with someone if I went to London parties. Course I did. Met Cosmo first party I went to in four years. He was the Lothario of SW10 and totally besotted with me.”

By then she had a three-year-old son, Bobby, and here is the bit that I find difficult to grasp on any level: she packs her bags and leaves the child behind. With new husband, the journalist Cosmo Landesman in tow, a set of black clothes and growing by-line celebrity through her iconoclastic articles in The Face(Stalin was a great guy; Annie Lennox should have died in a plane crash; Margaret Thatcher’s my heroine), Julie becomes the toast of Chatterersville.

Serious bucks begin to pour in: book deals, newspaper columns, screenplays. The launch party for her novel. Ambition, is held at the Ritz, where Julie sits on a flower-decked dais and various editors and interviewers are ushered up to the presence, one at a time, like serfs falling before a tsar. Her writing is as fresh, sharp and biting as a freshly squeezed lemon.

Occasionally, it is bilge, although no one seems to mind. Newspaper executives who rarely venture beyond the Savoy Grill are waving chequebooks, desperate to buy up a columnist who shoots from the lip and who supposedly knows where it’s at.

She won’t do no TV neither, so that makes her even more exclusive. Hacks talk about her in whispers. She’s the highest-paid journalist in the country and she does all her own housework. Apparently, she won’t go to lunch with an executive unless a taxi, plus a secretary, arrives. She’s scared of being on her own, you see.

More shock headlines from media gulch follow. After 11 years, she leaves Cosmo, loses custody of her second son, Jack, and goes off with “the world’s most beautiful woman”, Charlotte Raven, another journalist. “But I’m not gay,” she squeaks. “If you met Charlotte, you’d be very weird if you didn’t fancy her, too.”

By now she’s in Brighton, ditches Charlotte in favour of Charlotte’s 25-year-old brother, which Charlotte forgives. So they remain best friends and are currently writing a sitcom for the BBC. May I get personal here? “Sure.”

He’s twenty-something and you’re… well, how can I put it? “My weight! I’d be down the gymnasium if I wasn’t happy at home, wouldn’t I?” she sniggers. “He can’t keep up with me.”

Then she’s off, talking about the most important person in the universe. “Listen, I’m lazy. I don’t want to do what women of my age have to do to keep slim. If I could lose weight without walking round the block, without giving up one drink, one sweet, then I would. S’not like I’m gonna be a poster girl for fat people. Not like Dawn French. My idea of a great joke would be if Lenny Henry ran off with Kate Moss.”

So why Brighton? “Borders of Hove, actually, and it’s a sort of retirement home, innit? I have my boyfriend at night and Jack at weekends. Live a really, really normal life. The life of someone whose children have left home. Don’t go out much. Stay in with my boyfriend. Sounds pathetic, but you see, I packed so much in between the ages of 24 and 32 I’m way past my best now.

“And talent’s finite. Writing peaks after 12 years. I read some of my old stuff now and it makes my eyes water. It was so good when most people were rubbish. Like female columnists now. Reminds me what it’s like being at a dinner party with a crowd of beautifully groomed women who have nothing to say.

“Anyway, trying to cling to what you had when you were young would be so tragic, horrible, and after a certain age ambition is horribly disfiguring to the character.”

She writes for The Guardiannow, a paper that she would have dismissed once as cage-liner for tosspot liberals. “They are the only ones who will have me,” she admits brightly. “I was one of the most important people in London once. And London is like a village. People followed me round supermarkets so I had to leave, get away from the twitching lace curtains. Anyway, London’s crap, a rat-run. Be a bit pathetic for me to go on playing Queen of the Groucho Club with her Praetorian Guard like I did.”

For people, read tiny self-important circle of scribblers and PR people. She is endlessly fascinated by herself. “I’m odd. Odd background, odd parents. Paralytically shy when I first came to London. I knew it was make-or-break if I didn’t become a more interesting person. So I remade myself through a massive act of will and became this snarling, switchblade punk girl who had people like Emma Soames begging me to write for them.

“Quite something having a member of the Churchill family sucking up to you. I’m tough, had to be. My parents tried to protect me by telling me that I was nothing and I would amount to nothing. That’s why I’m so amazed when I hear middle-class parents telling their little bog-standard Imogens and Tims how wonderful they are. Nah, my parents never gave me confidence, didn’t believe in education as a way out.

“That’s a north of England, Scottish thing. They didn’t want out. My Mum was happy in the cardboard-box factory. I know I go on about them, but I do love them. Her father, a distillery worker, died recently. A good-looking man, union activist, lifelong communist, perhaps the template other men will never fit. Brilliant, my Dad. I thought nothing will ever hurt me as much again after he died. Thought I’d go mad with grief, like Ophelia.”

Feeling as she does, it becomes even more difficult to comprehend her forsaking her children. But she sidesteps the question. It remains out of bounds and none of the analytical relish she smears on other areas of her life is applied.

“All I am going to say about this is that the day I lost custody of Jack was the saddest day of my life. Even worse than my father dying. With Bobby, I was half-formed, a child myself. I don’t really know my first son. Came down and lived with me in Brighton for a year — his father didn’t like that — and he still lives here. What’s he think of me?” She laughs off the question. “He probably thinks that I’m a bit of a plonker.”

Any guilt? After a withering look, she becomes bolshie. “It never occurred to me to ask them for forgiveness. I mean, when they grow up and they haven’t made any mistakes, then they can tell me what to do.” What did her parents think?

“My parents were amazing grandparents, never reproached me. I realise now they backed off cos they were frightened I’d disappear, like I did when I was 15.” You don’t like babies then? “Sure, I love babies. I’ve got maternal instincts. Just prefer them when they get big and you can have sex with them.”

A knowing half-smile is followed by another giggling spasm. Playing daughter of the demon seed is one of her favourite roles. Except that the little voice and the constant hair-tugging dilute the impact, transforming the ramblings of a demented 40-year-old woman into the patter of a show-off child desperate to shock the adults.

“My background bred toughness. I’ve been bereft of things other people had. Didn’t go to university, didn’t have any old-boy network to media land, no one taught me to write. Don’t mind though cos it worked for me. My husbands hated it when I wrote cos I used to kill myself laughing. I was so funny. They couldn’t stand that it was so easy for me. Cosmo says I wrote in a trance. I’d sit down, black out and an hour or so later two-and-a-half thousand words would be there.”

She says: “I’m so happy now, happier than most people. I’m living the life I dreamt of living when I was a little girl. See, most people don’t like change. Terrified of it. They like their comfort food, comfort TV, comfort relationships. Me, I’m terrified of not changing. Don’t give a damn about last week or the last century, prefer the modern world.

“No nostalgia, never homesick. Don’t become attached to things and I don’t keep people close for too long. Seven years with me, usually — basically, after that you’ve squeezed all the juice out by then. Men! I’m cleverer than most of the men I’ve met. But I’ll never go out with a man of my own age. They go off men, you know, mentally.”

Listening to Julie, one wonders what all the fuss was about. She describes herself as a rogue gene. Wiser minds might counsel five years of intensive psychoanalysis. She curls up, screaming in derision as I read out some of the opinions that once made her compulsive reading. Like the fact that lesbians should be sent to concentration camps. “No, no, I couldn’t have said that.”

Then there was the prolonged worship of Mrs Thatcher. Howls of laughter: “Apologies, apologies. I can only put it down to some drug-induced trance. I’m such a coward. I used to hide behind Cosmo in case I’d meet people I’d slagged off, like Claire Rayner. She came across the room one night waving her fist at me, shouting, ‘You little bitch’. And I’m, like, behind Cosmo cowering, whimpering, ‘I’m not Julie Burchill. She’s a terrible person.’”

She relishes the awfulness that she has marketed so successfully: the little jeering, sharp-tongued chick in the playground whose idea of sport is maiming the vulnerable. “I don’t care,” she says. “People are too sensitive, and they shouldn’t be. Not if they’re in show-business. Why should they give a toss about my opinions? I don’t give a toss about anyone.”