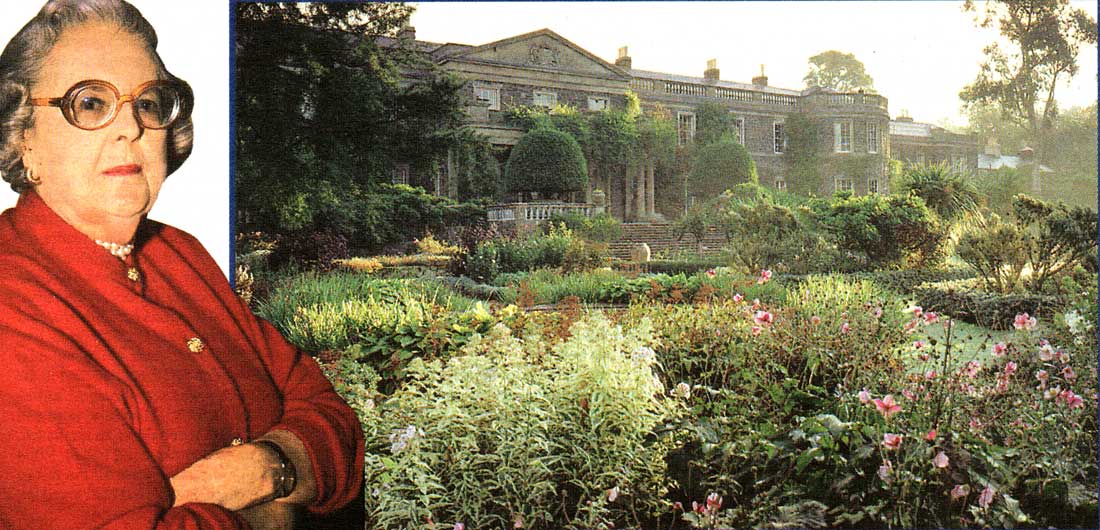

Lady Mairi Bury | The Daily Mail magazine, Weekend | February 1997

Lady Mairi Bury emerges from the shadows of a grand, beautifully faded drawing room at Mount Stewart, a house that symbolises Britain’s imperial past in Ireland. Built by her ancestors, the Londonderrys, the Georgian-pillared pile is a monument to aristocratic grandeur and lost dreams.

Lady Mairi Bury emerges from the shadows of a grand, beautifully faded drawing room at Mount Stewart, a house that symbolises Britain’s imperial past in Ireland. Built by her ancestors, the Londonderrys, the Georgian-pillared pile is a monument to aristocratic grandeur and lost dreams.

An enormously rich family, the Londonderrys were honoured by the Crown as faithful custodians of British rule and entrusted with the task of defending the island of Ireland from such upstart notions as republicanism. Lady Mairi’s mother, Edith Londonderry (pronounced Londondrey), was a formidable political hostess who threw lavish balls in Londonderry House, one of London’s last great aristocratic palaces.

The late marchioness held Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald in the palm of her hand, persuading him to give her husband a cabinet post. Her jewels were exquisite and included the legendary Londonderry tiara. She was also the doyenne of the devastating put-down.

Lady Mairi, who features in the second of BBC2’s new four-part series, The Aristocracy, has inherited the skill. While arranging this interview, I asked which was the nearest airport to Mount Stewart.

“If you don’t know where my house is,’ she said, “then I don’t think there is much point in you coming to see me.”

Eventually, directions were teased out. “Newtownards, about 40 minutes from Belfast City airport. Everybody knows Mount Stewart. It’s a famous house.” At one time, some might well have said infamous. Her father, Charles Stewart Henry Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Marquis of Londonderry and Secretary of State for Air, provoked huge controversy in the 1930s by making unofficial missions to Germany to see Hitler, and insisting his wife and the teenage Lady Mairi go with him.

She says, without a trace of embarrassment: “Father was trying to do his best. He wanted to bring about a rapport with Germany, felt that anything he might do to bring peace and avoid another catastrophe like World War I was worthwhile. My mother always thought there would be a war, which was why my coming out was brought forward. I was presented at Court when I was 16 so that I could still enjoy my parties.”

Lady Mairi even sat in on her father’s meetings with Hitler, Goering and Himmler. “Disappointingly ordinary people, rather stubborn I’m afraid,” she says, as if talking of anonymous civil servants rather than the Nazi hierarchy. But why was she there?

“I went about with my parents rather a lot. I was born when they were in their 40s, you see. With 20 years’ difference between me and my eldest sister, I’m afraid I was thoroughly spoilt. There was never any question of me not going with them to Germany. We flew in a Lufthansa flight, and once there we were given the use of Goering’s private jet.

“There were about three visits in all, including one during the 1936 Olympics. I was about 16 and, yes, quite interested when my father explained things to me. Like my contemporaries, I’m afraid I didn’t discuss the possibility of war much. I was too interested in flying and horses, I suppose.

“We went to visit Hitler on a number of occasions. But you see, sitting next to Hitler on a sofa didn’t mean much since he didn’t speak English, so it was rather difficult to understand what was going on. My father spoke German. Then again, Hitler was not a good listener and so he was rather difficult to talk to. Father thought him a very stubborn man.

“What did I think on meeting him? I thought, ‘What a nondescript person. Nothing at all like the one you see on newsreels. About 5ft 9in tall — you would never have picked him out in a crowd. No, I’m afraid there has no aura of evil. No sense of foreboding. A rather quiet voice. In fact, little stands out other than the memory of his most extraordinary blue eyes.

“Goering seemed the most eccentric. I remember meeting him nursing his baby, dressed in this rather elaborate swashbuckling uniform that made him look like Robin Hood. He took my mother’s maid to the opera a few times.

“You see, my father felt it had all started off so well in Germany, with all those factories giving the people mass employment while they made munitions and things. Then they got this power complex and began annexing everything. In the end, father knew it was hopeless and he simply gave up. He spoke German well enough to know Hitler was not getting the gist of things, just wouldn’t listen. I would hear him tell mother how pointless it all was, how he couldn’t get through to them, so set were they in their ideas.”

Though Lord Londonderry undoubtedly acted out of principle, controversy raged at the time. His meetings with the men who conceived and planned the Holocaust did not, understandably, meet with applause in every quarter. Critics thought him a naive meddler while stronger voices accused him of being sympathetic to Nazism.

“Nothing could have been further from the truth,” says Lady Mairi, equably. “He had lived through one hideous war and wanted to do everything possible to prevent another. Obviously, those who criticised him had absolutely no idea he was working for peace, and that for the sake of it my father would have gone anywhere, seen anyone. I find his motives deeply worthy. I’m deeply proud of those efforts. How could you not be?”

Lady Mairi’s nephew, the present Lord Londonderry, who appears with her in the BBC programme, agrees with his aunt’s view that her father was not a fascist. At the time, however, her brother. Viscount Castlereagh, believed otherwise and thought that his father, in company with other aristocrats like Oswald Mosley, harboured fascist views.

A family rift between him and his parents ended only nine years after the Marquis’s death, when his mother agreed to meet him in Claridges in London. “I shan’t talk about that,’ says Lady Mairi firmly. “Awfully silly business, family feuds. In the end you can never remember how they started off. Sons criticising fathers — nothing new about that — and a silly exchange of letters in our case, I seem to remember.”

Lady Mairi has other more glamorous memories of her childhood. As well as her mother’s dazzling parties, her father’s life-long enthusiasm for aviation led to him arranging flying lessons for the 12-year-old Lady Mairi — the family had their own private airstrip and several planes. Surely, her parents were an impossible act to follow?

“Not at all. My mother was the most marvellous friend. She was tremendous fun, terribly hard working. Ran three large houses, a shooting box in Rutland and still managed to design the gardens here, the most beautiful anywhere I’m told. I often wondered how she managed to squeeze so much into her day.’

Battalions of servants helped no doubt. Although the house and gardens now belong to the National Trust, hundreds of surrounding acres still belong to her ladyship. Divorced from her husband, Derek, Viscount Bury, in 1958, she now shares the 40-room, grey-stone house with a lady companion.

“My two daughters, Lady Elizabeth and Lady Rose, visit with their families of course. In the winter, when the house is closed to the public, I’m able to spread out a bit more.”

Lady Mairi is not, however, a chilling throwback to her mother. In fact, her looks owe more to Thora Hird, even if her accent remains quintessentially that of the Queen Mother. Studying her in the midst of that most elusive of decorating styles, lived-in grandeur, I couldn’t help thinking how, if you’d met her in the street, there would be no clue whatsoever to her past, her roots, or the centuries of inherited wealth and power that have gone into her genes.

Born in 1921 at a time when families such as hers still dominated Parliament and society, Lady Mairi sees lack of servants as the most radical change in society over the years. “One rather took it all for granted. In those days there were huge house parties; compared with now, the place was crowded with people.

“There were three footmen, a groom of chambers, butler and numerous house-maids and kitchen maids. I remember once we had two Spanish infantasstaying with us. My mother was friends with King Alfonso. The servants and the local people weren’t terribly pleased — they wondered why we were having the Pope’s daughters, as they called them, staying in the house.”

She smiles with just the merest hint of irony as her family, those uncompromising defenders of Protestant Unionism, look down from every wall in their heavily gilded frames. Lavishly dressed and uniformed, the Londonderrys have always been painted by the most fashionable portraitists of their day.

Understandably, it is the current political climate in Ireland which now concentrates much of Lady Mairi’s thoughts. “Trouble started, you see, when we let Ireland go. Now we have a complete stalemate. Made far too many concessions to the Irish government to stop the bloodshed. And, so far, all we’ve got is continuing bloodshed.

“My father thought of himself as an Ulster man. He came back here as Northern Ireland Minister of Education. Churchill, his cousin, warned him that by abandoning Westminster for Stormont he would ruin a political career. However, my father felt his duty lay with protecting the Union, as one still does, naturally.”

And with that, she eases herself out of her chair, strides across the rare Aubusson carpet, past the huge marble fireplace, and disappears into the gloom of the house. As she goes, it’s not hard to imagine the ghosts of the past echoing down the corridors.