The small teenage girl sat trembling at her school desk. In a short time, the 4 o’clock dismissal bell would ring and she would have to face the schoolmates who taunted her. Minutes later three girls attacked her as she walked towards home in the dark. They beat her so hard she could hardly stagger on to her parents’ tenement flat.

The small teenage girl sat trembling at her school desk. In a short time, the 4 o’clock dismissal bell would ring and she would have to face the schoolmates who taunted her. Minutes later three girls attacked her as she walked towards home in the dark. They beat her so hard she could hardly stagger on to her parents’ tenement flat.

This was Lulu growing up. “Don’t talk to me about happy schooldays,” she says. “Mine were a battle for survival. I hated the fear and violence. It was only after I left that I realised an argument didn’t automatically mean a punch-up.”

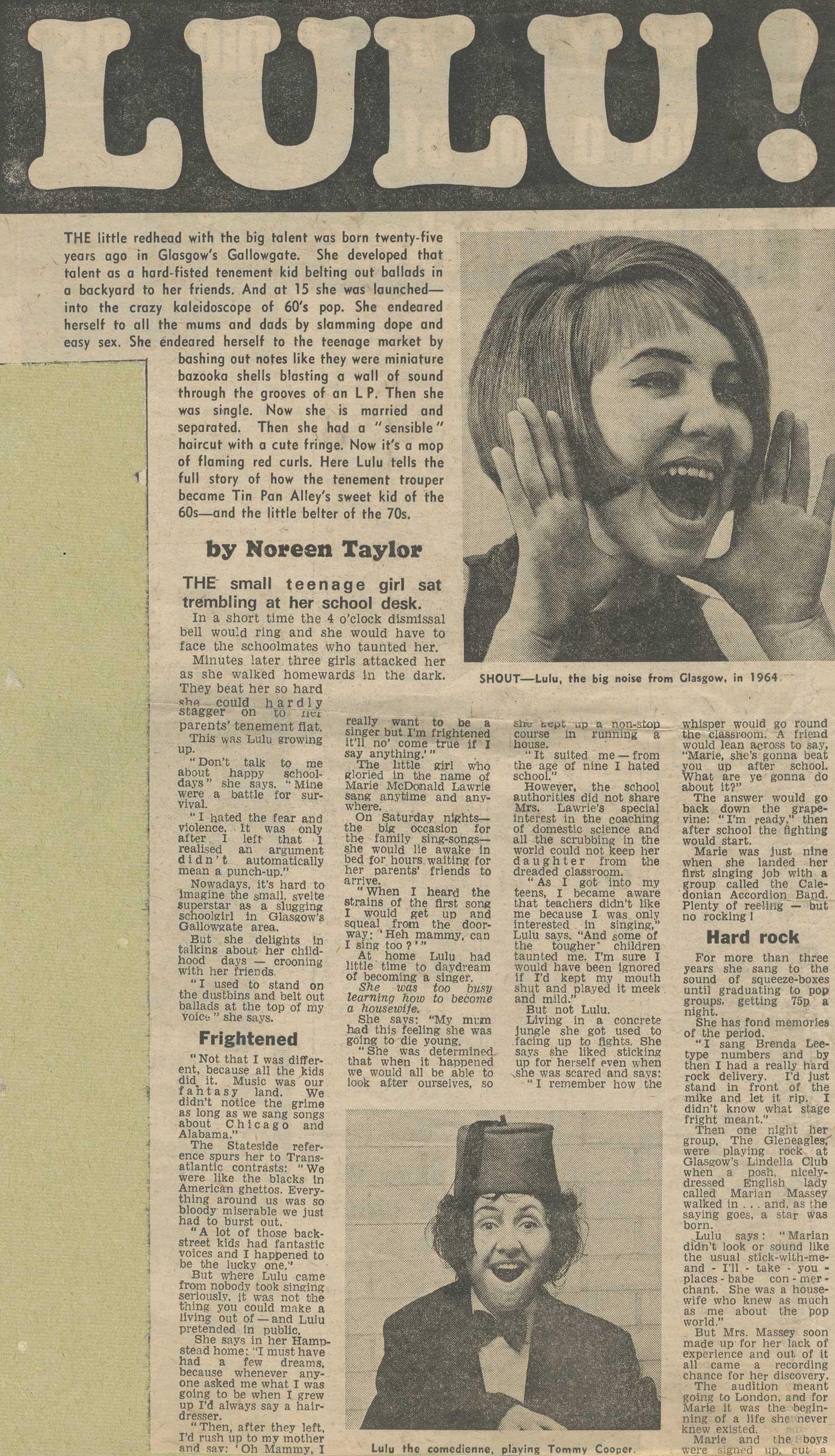

Nowadays, it’s hard to imagine the small, svelte superstar as a slugging schoolgirl in Glasgow’s Gallowgate area. But she delights In talking about her childhood days – crooning with her friends. “I used to stand on the dustbins and belt out ballads at the top of my voice,” she says. “Not that I was different, because all the kids did it. Music was our fantasy land. We didn’t notice the grime as long, as we sang songs about Chicago and Alabama.”

The Stateside reference spurs her to Transatlantic contrasts: “We were like the blacks in American ghettos. Everything around us was so bloody miserable we just had to burst out. A lot of those backstreet kids had fantastic voices and I happened to be the lucky one.”

But where Lulu came from nobody took singing seriously, it was not the thing you could make a living out of – and Lulu pretended in public. She says in her Hampstead home: “I must have had a few dreams, because whenever anyone asked me what I was going to be when I grew up I’d always say a hairdresser. Then, after they left,

I’d rush up to my mother and say, ‘Oh Mammy, I really want to be a singer but I’m frightened it’ll no come true if I say anything.’”

The little girl who gloried in the name of Marie McDonald Lawrie sang anytime and anywhere. On Saturday nights – the big occasion for the family sing-songs – she would lie awake in bed for hours waiting for her parents’ friends to arrive. “When I heard the strains of the first song I would get up and squeal from the doorway, ‘Hey mammy, can I sing too?”

At home Lulu had little time to daydream of becoming a singer.

She was too busy learning how to become a housewife. She says: “My mum had this feeling she was going to die young. She was determined that when it happened we would all be able to look after ourselves, so she kept up a non-stop course in running a house. It suited me – from the age of nine I hated school.”

However, the school authorities did not share Mrs Lawrie’s special

interest in the coaching of domestic science, and all the scrubbing in the world could not keep her daughter from the dreaded classroom.

“As I got into my teens, I became aware that teachers didn’t like me because I was only interested in singing,” Lulu says. “And some of the tougher children taunted me. I’m sure I would have been ignored if I’d kept my mouth shut and played it meek and mild.”

But not Lulu. Living in a concrete jungle she got used to facing up to fights. She says she liked sticking up for herself even when she was scared and says: “I remember how the whisper would go round

the classroom. A friend would lean across to say, “Marie, she’s gonna beat you up after school. What are ye gonna do about it?” The answer would go back down the grapevine: “I’m ready.” Then, after school, the fighting would start.

Marie was just nine when she landed her first singing job with a group called the Caledonian Accordion Band. Plenty of reeling – but no rocking. For more than three years she sang to the sound of squeeze-boxes until graduating to pop groups, getting 75p a night.

She has fond memories of the period. “I sang Brenda Lee-type numbers and by then I had a really hard rock delivery. I’d just stand in front of the mike and let it rip. I didn’t know what stage fright meant.”

Then one night her group, The Gleneagles, were playing rock at Glasgow’s Lindella Club when a posh, nicely-dressed English lady called Marian Massey walked in… and, as the saying goes, a star was born. Lulu says: “Marian didn’t look or sound like the usual stick-with-me-and-I’ll-take-you-places-babe con-merchant. She was a housewife who knew as much as me about the pop world.”

But Mrs Massey soon made up for her lack of experience and out of it all came a recording chance for her discovery. The audition meant going to London, and for Marie it was the beginning of a life she never knew existed. Marie and the boys were signed up to cut a couple of numbers and then went back to Glasgow.

She returned to school for a couple of months to face yet more taunts. But her jealous pals were about to learn a swift lesson – the girl next door can be an overnight star. For when the record “Shout” reached the shops it was a smash hit. And Marie and The Gleneagles had been transformed into Lulu and The Luvvers.

“Marian came up with my name,” says Lulu. “She thought I was a right Lulu, as simple as that.” We are interrupted by Lulu’s assistant: a radio crew are waiting to speak to her, can she spare a moment? She nods, walks out of the dining room into a luxurious sitting room and I watch as she helps a nervous interviewer through the talk.

How different from the gauche moment when she, too, was confronted by a star. A couple of months after achieving fame,

Glasgow’s Marie met Liverpool’s Priscilla. Lulu said: “Oh look, my hair’s the same colour as yours.” Said Cilla Black: “I don’t think so.” And it was to be a long time before they spoke again. “I was too embarrassed,” says Lulu. “Now we chat during breaks in the BBC canteen.”

Any sort of communication was a problem. “I seemed to speak a different language from everyone else. I spent most of my time miming instead of talking.” On stage, though, she came across fine.

By now, she and the boys travelled the country, doing one-night stands and fitting in TV appearances. And they were earning big money.

“It took some time before I realised there was cash around. Anyway, my accountant allowed me £10 a week until I was seventeen. Then I got a cheque book and I discovered what shopping sprees were all about.” Money wasn’t all she learned to appreciate in those early years. Like any young girl, she found she’d get a kick out of men.

For three years, from the age of thirteen, the only boy in her life was Alex Bell, one of the Luvvers. They took it for granted they would get

married. But when Lulu and the group split up she waved goodbye to her special Luvver. And, like many other females in Britain, she

fell in love with that handsome hero of pop, Scott Walker.

But unlike other girls, she had the chance to meet him as an equal.

“All those fans must have thought I was lucky. In fact, he ignored

all my romantic advances and talked to me like a mate interested

in music,” she said. She recovered from her crush – to fall in and out

of love a hundred times.

She dated Georgie Best and David Frost. And she dated the

man who was to cancel out everyone else and become her

husband – Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees.

DAY TWO:

The marriage that went wrong from the start

Lulu’s wedding wedding day was an amazingly accurate foretaste of her marriage: It just didn’t go as planned. She and Maurice Gibb could not face the usual showbiz hullabaloo, so they decided to keep the wedding a secret. They chose what they imagined would be an

obscure place – Gerrard’s Cross, Bucks. But a wise-guy friend had other ideas. To give them a big surprise he tipped off the newspapers the night before.

Lulu says: “I had to beg the crowds to let me through into the church.

All the autograph books and Press cameras I dreaded were there In force.” However, she emerged as Mrs Gibb and that, after all, was what counted. “I’d put up with all sorts of warnings in the months before… ‘why don’t you wait?’… ‘try living together, first.’ I didn’t need to live with him to see if I liked him enough – I was simply mad about him. He made me relax, he made me laugh. Like me, he was young and so we shared the problems and adventures of growing up together.”

Lulu was twenty and Bee Gee Maurice was a year younger. They had known each other for two years. It was the Number One pop wedding of the year and the world wished them well. Their married life started in style. They honeymooned in Acapulco, then moved into a huge Hampstead house with a double garage. Inside: a Rolls for him and a Mercedes for her.

Lulu was being introduced to the kind of high living in which Maurice revelled. He overwhelmed her with presents and their first weekend away together was carried out in jet-set fashion. They flew to Paris, stayed at the George V Hotel, one of the world’s most exclusive. Lulu recalls: “I awoke to find a bottle of champagne and a dish of caviar for breakfast.”

But as the months of their marriage passed friends began to point out that what Lulu called Maurice’s generosity was in fact extravagance. They were both earning well, of course. But the way they worked was hardly a recipe for a good marriage. Their separate career commitments involving international travel, kept them apart for long periods.

Says Lulu: “A typical month might be taken up with two weeks of one-night concerts in Europe, a quick return to London for a TV spot and then a week recording in the States. Just keeping in touch was difficult, and although we tried hard to overcome the problems, sometimes the strain showed through. I was appearing in Las Vegas and we were phoning each other twice a day. Suddenly, we felt we couldn’t stand being apart much longer and he flew out from

England to be with me.”

Lulu’s m a n a g e r – Marian Massey – offered a possible solution.

She asked the singer to give her vocal chords a rest for a year or two. During that period, she said, Lulu and Maurice could concentrate on their marriage and maybe start a family. It would also give Lulu time to look over her past career and plan for the future.

“I did think about it seriously,” says Lulu. “But there was no way I could imagine giving up work in spite of wanting a family as well. I’d been working since I was a kid. And at the end of a week off I’m so bored I can hardly wait to get back. The thought of all those empty months ahead was too much.”

Inevitably, they grew apart. Not quickly, because they tried to patch up their differences. But the marriage had to finish. Lulu is tactful about her husband. “Maurice is a great guv,” she says in a way which makes you believe her. So there she was – twenty-three years old. Smash hit records and a smashed-up marriage behind her.

She wasn’t going to retreat to Glasgow or rest on her golden discs in Hampstead. She threw herself into work. “I was completely unprepared for the let-down after we split up. I had a kind of delayed shock. It seemed as if everything was slipping from my life. Often I’d be singing on stage with tears streaming down my cheeks. I know now it was work which kept me from breaking down.”

Lulu has had a ferocious work record since she began eleven years ago. And, in spite of the regular concerts and TV appearances, she has been unable to resist a challenge. There was the strain of singing Boom Bang A Bang for Britain in the Eurovision Song Contest. She tied for first place with three others.

Then there was the occasion she. joked with a film director and ended up with Sidney Poitier in To Sir With Love. “This guy came backstage one night after a show to say if you change the colour of your hair you can be in my film. I just looked him over and said: ‘Aye, that’ll be right.’ He laughed his head off and told me I was the cheeky kid he needed so I got the part.” The star of stage and small screen was less than enthusiastic about her big screen image and when she saw herself in the cinema she says she ran away to hide.

But American audiences did the opposite. The film’s title song, by Lulu, went to the top of the US charts, and she was invited over. In the film she played a cameo role as a Cockney sparrow. It was a shock for the Americans when they realised their new favourite was a Glaswegian bird. Her TV chat show opening – “Am no English ye understand” – made them laugh still more.

The Glasgow Cockney proved a big hit in the States, wowing audiences in Las Vegas and West Coast night spots. But on her return to Britain the star was brought down to earth by her mother: “Marie,

people in Glasgow think you’re becoming awful phoney with that accent.” What did knock her parents out with pride more than Lulu’s money and fame was when she met the Queen. The photograph, taken at the Royal Command Performance. is the centrepiece on the sideboard.

The Scots pop queen met American royalty too. The king of song. But there have been moments in Lulu’s show business career when she wished the earth would swallow her up. “One night I was larking about on a stage that turned out to be slippery. My high-heeled

boots became ice skates and I went, into a long slide, finishing up down under the piano. Another time my catsuit burst down the

front. I know it was opening night but that was ridiculous!”

The embarrassing incident to beat them all came during her first American visit. It was the magic moment she had dreamed of since her childhood – starring at the Coconut Grove in Los Angeles. Lulu wasn’t singing with her own band and when she launched into a big rock number she found the rhythm and brass sections were playing different tunes.

Says Lulu: “I just blurted out something about there being a language barrier but I was dying of shame.” It was, she says with conviction, one of the rare occasions when she felt like giving up showbiz for good. Embarrassing moments are not exclusive to the stage.

“Like a lot of females in show business I have a small following of weirdos. Some send sick letters and one or two even arrive on mydoorstep. One guy wanted me to go off with him to spend the £250 he’d saved up. Another barged in and told my housekeeper she was fired because he was taking over.”

Most fans are “wonderful.” She even has followers in Japan. Her fans have changed of course. She started as a rocker but has mellowed into a balladeer, performing the kind of number her Mum says “used to make yer grandad cry.” Lulu says: “Now I’ve learned to control and vary my voice it means I’m no longer stuck in the pop groove. I suppose that sounds like a sell-out to the other rock singers but I want to be the sort of entertainer who appeals to everyone.”

She certainly appeals to the BBC – she’s currently filming her tenth series. But the transformation from the stand-and-deliver rock n’roll shouter to the soft-shoe- shuffle, middle-of-the-road swinger has been an expensive one. “It costs me a lot more to put on a show now. Where once I was all right in trousers and tee-shirt I now have to spend £300 on an outfit, and I need a wardrobe of stage clothes.”

She’s in a vicious circle. The more she earns the more she has to spend. And she makes the typical superstar, super-taxed complaint about money. “If I make £1.000, more than half goes to the Government. With the rest I have to pay musicians, accountants, lawyers, publicists and more.”

Lulu has a disconcerting habit of smashing her public image.

“People have me all wrong. Writers have labelled me as a cuddly little tartan bundle. That’s rubbish. I hate being described like that. I’m a woman. Even now I can feel the cocky devil-may-care attitude of my early years is disappearing.”

And with the passing of years comes sadness, too. “I’ve squeezed so much into, my life and yet I’m without the one thing I’m really crazy about – children. “I would desperately like to have a family.” A tour round her house shows her sincerity. On the top floor she opens a door and sighs wistfully: “This was going, to be the nursery. Maurice and I talked about six kids.”

Lulu’s wedding plans and marriage plans and family plans did not work out. But she has an enviable success rate when confronted with a challenge. If she makes motherhood a challenge instead of a dream maybe her rich young life will one day be complete.