Lady Longford | The Times | 1999

Outside the Longfords’ London flat is a note written by their daughter, Lady Antonia Fraser, warning visitors to be patient because it may take the occupants some time to answer.

Outside the Longfords’ London flat is a note written by their daughter, Lady Antonia Fraser, warning visitors to be patient because it may take the occupants some time to answer.

At 93, while walking is obviously irksome for Elizabeth Longford, she remains in sparkling form: impeccably groomed and smooth-skinned with, it seems, a complete grasp of the trends, gossip and news shaping today’s world. After all, how many nonagenarians are publicising their latest book?

When she greets me with a smile — “So lovely of you to come and see me” — I realise that, apart from her fragility, the gracious manners are one of the few clues to her being born during the Edwardian era. In the sitting room, beside her favourite chair, is her new biography of Queen Victoria, a follow-up to her well-received 1964 study Victoria R.I. Memorabilia of Britain’s longest-lived monarch jostles for space with photographs of glamorous daughters and granddaughters.

A bronze head sits on a bureau, while prints and sketches crowd the walls of the Chelsea flat. The Longfords live in London during the week, spending weekends and holidays in their East Sussex country house. “I’d much rather stay in the country all the time,” she says, “but Frank likes to come to London, to be at the House of Lords. Of course, we like going to parties, too.”

(An hereditary peer, Longford has been rescued from oblivion by being granted a life peerage). The telephone rings frequently, suggesting that the Longfords, unlike most elderly couples, are both busy and sought-after. One caller asks to speak to Lord Longford.

“He’s out, doing a radio show. Jimmy-something-or-other… Young? Yes, that’s it.”

A daughter, Judith, calls: “You’ve flown in from America? Of course I’m not too busy to see you. Right now, any time, darling.” Incredible as it may seem, Lady Longford did not begin writing her historical biographies, which include Wellington and Byron, until her mid-fifties. The eldest child of two doctors, she was brought up in London, within that privileged, prosperous class she variously describes as “upper-middle” or “professional”.

A daughter, Judith, calls: “You’ve flown in from America? Of course I’m not too busy to see you. Right now, any time, darling.” Incredible as it may seem, Lady Longford did not begin writing her historical biographies, which include Wellington and Byron, until her mid-fifties. The eldest child of two doctors, she was brought up in London, within that privileged, prosperous class she variously describes as “upper-middle” or “professional”.

Clever and beautiful, she read classics at Oxford, where she came across the Workers’ Educational Association. “I became a socialist during the lectures I gave for the WEA when I learnt how the majority of people lived, and how they were forced to leave school at 14, while hungering for an education, something I’d been fortunate to take for granted.”

At 25, she married into the aristocracy after falling in love with Pakenham. She converted him to socialism, and he converted her to Roman Catholicism. When I asked whether, after almost 70 years together, they still managed to surprise one another, she replied promptly: “Of course, and not just occasionally. I find him stimulating always. Frank never stops talking — always has masses of things to tell me.”

Between the wars she stood as a Labour candidate during elections, although the demands of motherhood and domesticity eventually took over. She worked from home, writing newspaper columns that advised readers how to cope with housework and children. Mother of eight, grandmother of 26, great-grandmother of seven, she and her husband remain a unifying force amid the spreading tribe of Pakenhams, Billingtons, Frasers and Fitzgeralds, many of them writers themselves.

“I’m very lucky,” she says of her family. “They bring food around and we have picnic lunches here every week, which are great fun.”

As with her close friend, the Queen Mother, the phrase ‘great fun’ punctuates so much of her conversation, revealing an openness and interest in all around her, especially the youngest of her family.

She is also friendly with the Queen and that, presumably, made access to the Windsor archives easier. She smiles without answering. There is new material in her book that she could not have published without special permission. It includes a letter written by Queen Victoria to her doctor, in which the mother of nine children criticises her eldest, highly strung, daughter for breast-feeding: “Vicky was unsuited to the essential animal duty of nursing. The more animal the wet nurse, the better.”

Lady Longford says: “When I was asked to do the book, I was delighted. It was such a long time since the previous one. And in some ways, I’m more sympathetic to Victoria now, more admiring of her and her achievements, especially her ability to focus her status on the majority of her people for whom she was the supreme head of state — although, not being an intellectual, she had no sense of understanding of law or of how a constitutional monarchy worked.

“When a minister once referred to her as Queen of a democracy, she drew back in horror, declaring that she would rather emigrate to Australia than live in such a place. Her accession to the throne was anything but smooth, partly because of her extraordinary childhood. She wouldn’t have got anywhere unless she’d fought. Therefore, she didn’t have the sublime confidence of the autocrat or the great monarch.

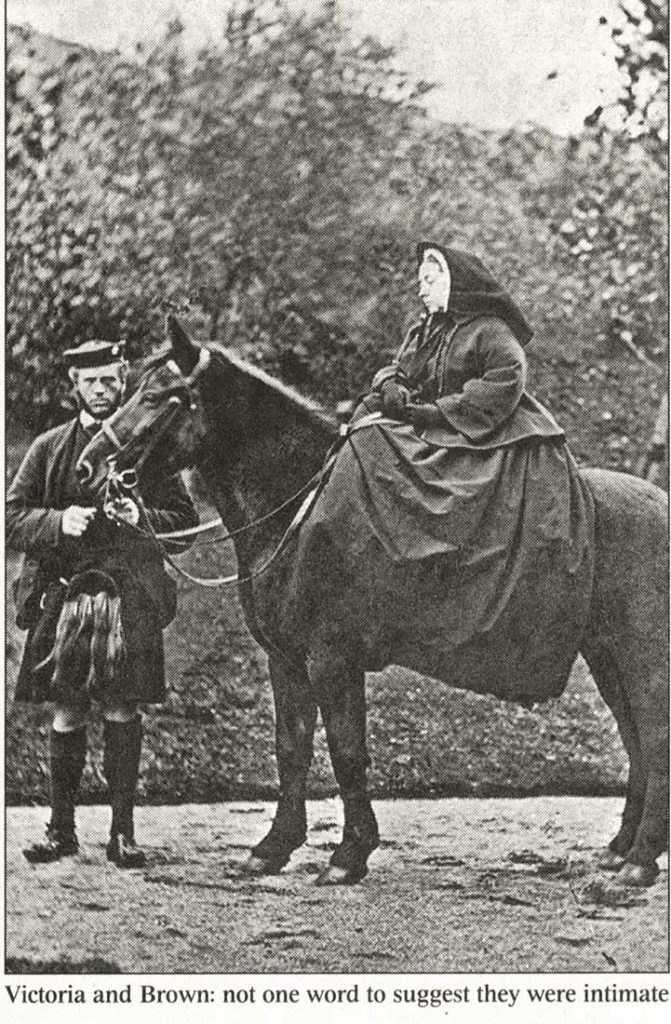

“The pushy insecurity which marked her behaviour had more in common with the bourgeoisie, making her tremendously dependent on those she loved and on certain servants. By the way, there is no evidence whatsoever that the Queen had an affair with John Brown.

“For a start, there were too many people around for them not to have been caught out over the years if they had been lovers. People were in and out of her rooms the whole time, yet in all the personal journals I’ve read, those written by friends and servants, I have not come across one word suggesting they were intimate.”

The picture of Victoria painted by Lady Longford and other biographers cannot help but reveal a person who, if alive today, would be described as capricious, selfish and full of contradictions and demands. She could also be callous. On being asked what happened to the “poor Irish” evicted by their landlords during the famine, one of her Prime Ministers answered: “They became absorbed somehow or other.” This cynical response set the Queen off laughing.

“Selfish, perhaps,” says Lady Longford. “But we mustn’t be too hard on her. You see, I don’t believe you can remain the centre of so many people’s lives without becoming egocentric.” But she is quick to avoid an unseemly analogy.

“I don’t think our present Queen is selfish. But then HM’s upbringing was entirely different, with loving parents. Her father trained and taught her, as opposed to Victoria who spent her life searching for one. Compared to Victoria’s lonely childhood, the present Queen had constant companionship with her young sister.”

Asked what Victoria shares with her great-great-grand-daughter, the Queen, Lady Longford pauses for a moment. The struggle between friend and historian is evident. Eventually opting for the diplomacy required by membership of that exclusive circle, she says: “Well, neither of them were academics or intellectually inclined. Both loved animals and children. After all, four children these days might be considered equal to Victoria’s nine.

“As for the Queen’s presence, while she is not formidable, no one would be tempted to make silly jokes or behave in an undignified manner in her company. Duty is a word that was continually mentioned by Victoria, as it is with the Queen. And both have the sort of faces that change dramatically when they smile.

“The present Queen is very proud of her ancestor and would be upset if anything horrid came out. For instance, recently the Queen received a letter from a Portuguese man claiming to be a descendant of an illegitimate baby born from a supposed liaison between Victoria when she was 15 and the Duke of Wellington.

“Her Majesty wrote back asking the man to please leave Queen Victoria in peace. Significant, I thought of her affection for Victoria.”