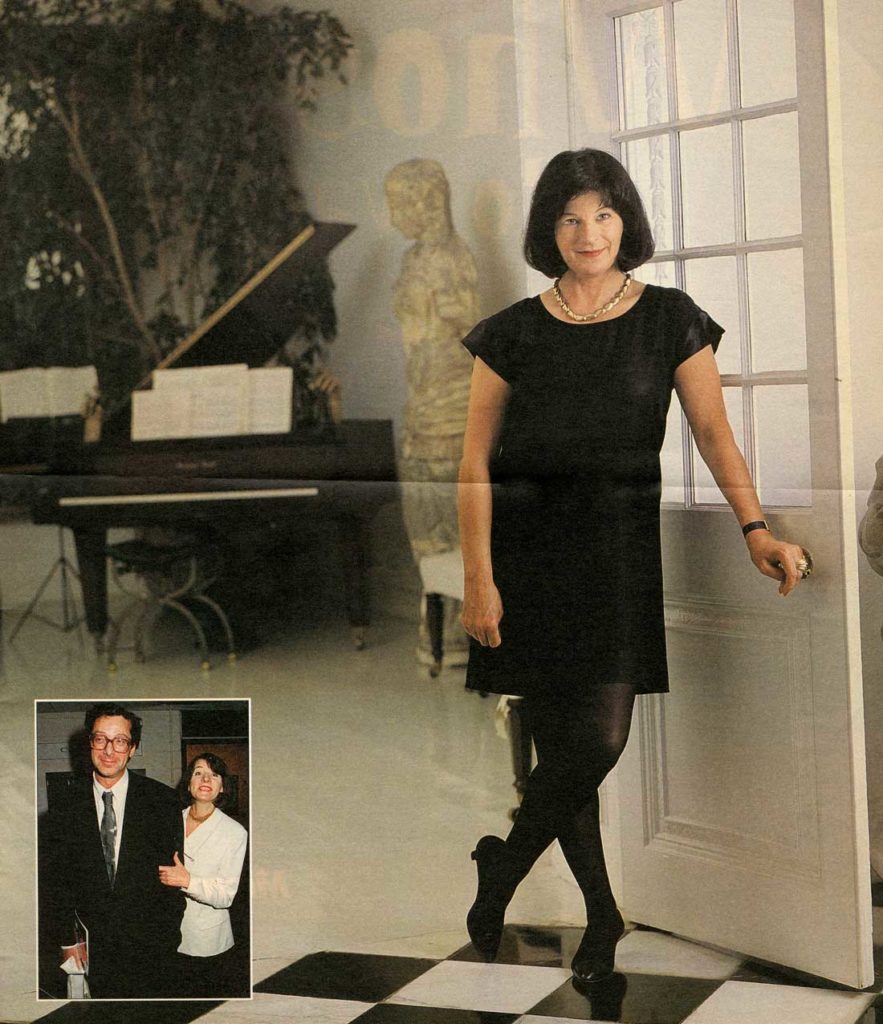

Josephine Hart | The Daily Mail magazine | June 1995

Josephine Hart is a woman with a power to disturb. Two slim, but oh-so-lethal, best-selling novels testify to that power. Damage, the story of a man’s erotic obsession for his son’s fiancée became a film starring Jeremy Irons and Miranda Richardson.

Josephine Hart is a woman with a power to disturb. Two slim, but oh-so-lethal, best-selling novels testify to that power. Damage, the story of a man’s erotic obsession for his son’s fiancée became a film starring Jeremy Irons and Miranda Richardson.

Sinwas about another kind of obsession: a woman’s envy for her adopted sister grows into a cannibalistic hatred, almost devouring them both in the process. The third. Oblivion, has just been published. This time the theme is death.

You would not have tripped off to bed lightly after a session with any of these dark books. What’s more, you would have wondered about the woman who had created them. About the mind that could have gone down such twisted corridors, laid bare the psychological fetishism, and kept the reader dangling in discomfort until the final page.

Predictably. Josephine Hart is a woman who has struggled with her own demons. A woman who has fought and seems to have won. A woman whose own story is as poignant as those of the broken people she has created in her fiction. Not that any of this is apparent from the outset.

A maid answers the door of the Mayfair house. From the top of an elegant, white staircase a woman’s voice calls down. It is oddly out of sync with her surroundings. “Hello there. How are you? Come in, for heaven’s sake.” The voice is a surprise. It’s warm, homely. The accent is Irish, from the small town of Mullingar in County Westmeath, and a long way from the house with the marble hall and all that it represents.

But then maybe we shouldn’t be too surprised. For the couple who live here have both been crowned with golden halos of success. For 12 years, Josephine has been happily married to the advertising genius, Maurice Saatchi. They have a ten-year-old son, Edward. And there is also Adam, the 19-year-old son from her first marriage.

Surprisingly, although it is a bright summer’s day, she is dressed in the uniform usually seen at cocktail parties. Black stilettos, black tights and a very short, black, sleeveless dress. Lips and nails are red. Jewellery is heavy gold. “Do you like the dress?” she asks. “It’s an old St Laurent I used to wear about ten years ago. I’ve had the shoulder pads taken out and I’m going to have it copied again. Maybe in white. Maurice would love that. Poor thing, he got fed up with the leggings I’ve been wearing for ever. He complained that he never saw my legs.”

She is a handsome, impressive-looking woman of 52. Hers is a knowing face, the kind that draws people in a crowded room. Her pale blue eyes arc less open. They are like twin beams of light — sharp, on the alert. The maid brings a tray of tea and coffee. Josephine speaks kindly, without the whine of the spoilt, rich wife. When the maid leaves we talk of death. But it’s neither awkward nor tense. Death has stalked this woman’s life. A therapist might say that she talks about it. deals with it and writes about it in order to arm herself against its shadows.

Josephine comes from a family who watched three children die. A baby brother died when she was six. When she was 17, her invalid sister Sheila died. Six months later, her brother Owen died and. to this day, she cannot bear to talk about it. “When you have endured that kind of grief, you are never careless of life,” she says. Had she ever thought of therapy?

“Never — I can’t bear all the self-absorption. The Irish tend not to.”

Perhaps the writing was therapy? “It took me a long time to write. I had to run from anything creative that led towards any emotions. I had these novels in my head but I wouldn’t commit them to paper. It wasn’t a case of I can’t, but I won’t — the opposite of writer’s block. Then Maurice said, ‘Enough of this cowardice. You must face up to whatever is in there for your own sake.’

“I admire M’s mind so much,” she says. “He sees everything I write, long before anyone else. He was very aware that I was in this shadow land of grief for my family. M has had a lucky life. So, it was interesting to watch how he reacted to recent events.”

The events she is talking about took place last December, when Maurice Saatchi was forced to resign as chairman of Saatchi & Saatchi, the advertising empire he founded in 1970 with his brother, Charles. Unsympathetic shareholders, and the new breed of money men who thought him flamboyant, were blamed for ousting him.

The company the brothers had made famous with campaigns for British Airways, Castlemaine XXXX. not to mention the Conservative Party, had fallen into other hands. The kind Maurice refers to as bean counters. The prevailing view, which the brothers dispute, is that the empire was lost because they spread their wings too far and because of their financial naiveté.

They are now building a new company, M & C Saatchi, and a string of prestigious clients, who presumably care little for the bean counters, have followed them aboard. “What happened was so

senseless, but Maurice acted well,” says Josephine. “He was courageous throughout. It was a drama all right, but an intriguing one. I’d always known how clever and kind he was, so it was comforting for me to know that others thought so as well. So many of those who have worked for him have now followed him into the new company.”

It’s a cool response to what must have been a traumatic time for her husband. She disagrees. “There are serious, deep down problems in life, and this was not one of them. We have so much else. We’re not the sort of couple who go off and enjoy hobbies, so we are able to spend all our free time together, to take long walks where we talk and listen. It is a joy for me to have found someone I am in total communication with.”

These confidences sound neither mawkish nor insincere. “I know how lucky we are to have this great love. I’ve noticed that other women who are blessed with a marriage like mine have a special glow about them. They practically bloom with love. Money, success, they would mean nothing to me without the pleasure of a loving marriage.

“My parents knew great love. Their love was tested beyond endurance, yet they were able to take what came because they were so blessed in their relationship. They couldn’t go out for years because of my sister’s illness, but they had each other, and they had their books. They were grand people. They were lovers in the deepest way.

“If you have lived with people who have loved like that, then you search for it. My marriage is the foundation of my life. I don’t go anywhere without M, and he doesn’t go anywhere without me. I’d drop everything to have lunch with him, and we have dinner together every night of the week. And why not? You get married to be together.”

We are sitting in a long, white room on deep, white sofas. The interior design was created by Maurice — there are pieces of sculpture, paintings, a row of pink chairs and, next to the fireplace, the most enormous basket filled with logs, This is not so much a private sitting room, more a theatrical setting. I couldn’t help thinking how far it all was from the small bungalow in Mullingar. And how her world had changed.

And yet, from the hearth of her small Irish home, evolved the framework that provided Josephine with her sense of discipline, and her confidence. In the Fifties, Mullingar had only 7,000 residents, and many of those would have been farming families with small plots and a dozen head of cattle. Yet those residents were highly cultured, they formed poetry societies, drama groups, recital and musical classes where children learned traditional Irish dancing and songs.

Josephine’s mother was a housewife, and her father was co-owner of the local garage. “I thought all women were housewives. I thought they only worked if their husbands had died. But my mother adored being at home. Life was always an adventure for her. We talked about books and poetry. I was left with the ideal that to be a wise woman was the most wonderful thing.”

When she was 12, Josephine won a scholarship to St Louis, a boarding school in Carrickmacross, Monaghan, one of the top

academic schools in the country. “I have such fond memories of that school and the nuns who taught there, although I know it’s not fashionable to praise nuns any more. It was hard and strict, but I was a serious, intense child, so I fitted in quite naturally. My education has left me with a disciplined mind, deep powers of concentration and so many beautiful memories.

“There was Latin mass every morning, the nuns brought me tea and honey when I had pneumonia, and like all the other girls, I polished the floorboards with dusters wrapped round my feet.” Many dreamed of escaping the strict confines of a rural Irish upbringing but Josephine was one of those content to stay. It was her parents who felt she deserved more.

“I stayed at home until I was 22. It was an odd, closed-in sort of life, and I was a rather odd, intense little person, far too old for my years. But my parents were never critical. 1 was much less calm and serene than my mother. Yet she never tried to subdue me or change me. She

didn’t need to reproduce herself in me the way some parents do.

“Yet they had such grief in their lives, the kind of grief that destabilises sanity. I do not know how my mother remained sane. When parents have to bury their children three times, it is like a Greek tragedy.”

When Josephine left home she headed for London. In the era of Biba, free love and all the madness of the mid-Sixties, Josephine the serious, dutiful daughter must have seemed like an alien. “Oh, you would have found me very dull — I couldn’t play the wild daughter. I didn’t want to give Mama and my father the slightest cause for worry. I had never known the luxury of youth. By the time I was a teenager I knew everything.”

She shared a flat with two other girls in Holland Park, worked in a tele sales office, and paid for acting lessons at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. “I still wanted to be an actress, but I had to end the lessons. All the emotional digging around you have to do in order to act became too painful a process after the deaths.”

Needing the safe predictability found in certain office work, she joined Haymarket Press, publishers of business magazines. Eventually, the hardworking girl who had anaesthetised herself in

office tedium in order to find some semblance of normality, became a director. “I was good at the job, very efficient, and highly paid. I didn’t care all that much about any of it though.”

It was at Haymarket that she met her first husband, Paul Buckley, the man she was married to for seven years. Out of deference to her son, she won’t go into details about the divorce, and the beginning of her love affair with Maurice. All she will say is that he was pleasant and a kind husband, and that she is still fond of him. Perhaps a husband who did not invoke any heart-stopping tremors was in keeping with the rest of the life she was living.

It seems that her emotions were on hold until the early Eighties when she married Maurice. Her looks, everything about her, seem to have undergone a physical and spiritual renewal after that marriage. The greying hair was cut into a smart bob, and coloured back to its original black. She rediscovered her passion for poetry, theatre and books, organising recitals and staging theatre productions.

Her social life also became glamorous, smarter, faster. Her parents looked on proudly. “They are both dead now. When Mama died in

1986, my hair turned white. I was heartbroken.” After her mother’s death, Josephine spoke to Maurice about all that was going on in her mind. The stories, plots and characters that had begun to haunt her.

“One Saturday morning he said to me, ‘Go into your study, close the door and write a thousand words.’ Do I dare do this, I thought, and then the first chapter of Damagejust poured out. 1 didn’t even have to think about it. For years these people had been living in my head. When I’d finished 10,000 words, I put it away. Forgot about it.”

Months later, with more encouragement from Maurice, she found a literary agent and the book was published. “Sometimes I find writing so painful. Of the three, Sinwas especially traumatic. There were times working on that book when I thought, ‘My God. I can’t bear any more of this,’ especially writing the scene where the boys drowned.”

After her own experiences she could have become neurotic about her own sons’ safety. “To my credit, I haven’t,” she says. “I have always thought it would be wrong to place my burden on their lives.” She has little of the migrant’s longing to return to Ireland. “I couldn’t live there now.” Too much pain, I suspect. “There is that,” she agrees. “But I’m perfectly at home in London.

“It’s an easy, undemanding, soothing place for such an important city. Not that living here makes me any less Irish. I keep my name and my Irish passport and that little house in Mullingar which I stand outside because I just can’t bear to go in. But I’ve grown used to London, and rather like the feeling of being the foreigner, the outsider.”