John Aspinall | The Times | July 1999

It is so very hard to view the figure reclining on a sofa as the arrogant, right-wing buck about Belgravia, inveterate gambler, ringmaster of the Lucan set and controversial zoo-owner. For John Aspinall is suffering from cancer of the jaw, his face ravaged by surgery.

It is so very hard to view the figure reclining on a sofa as the arrogant, right-wing buck about Belgravia, inveterate gambler, ringmaster of the Lucan set and controversial zoo-owner. For John Aspinall is suffering from cancer of the jaw, his face ravaged by surgery.

Although he will hate me for saying so, the effects of the disease have given him an aura of vulnerability. It has not, he wants to make crystal clear, changed his philosophy. “Illness hasn’t moved me from any of my entrenched positions. I assure you, I’m more set in my ways than ever.”

The words are said without passion. Perhaps the wish to provoke and amuse never dies. We meet in the darkened library of Howletts, the grand 18th-century Palladian house near Canterbury that he bought after an impressive win on the races in 1956 when he was 29. With it came 39 acres of parkland, which he turned into a private zoo for his elephants, tigers, gorillas and rhinos.

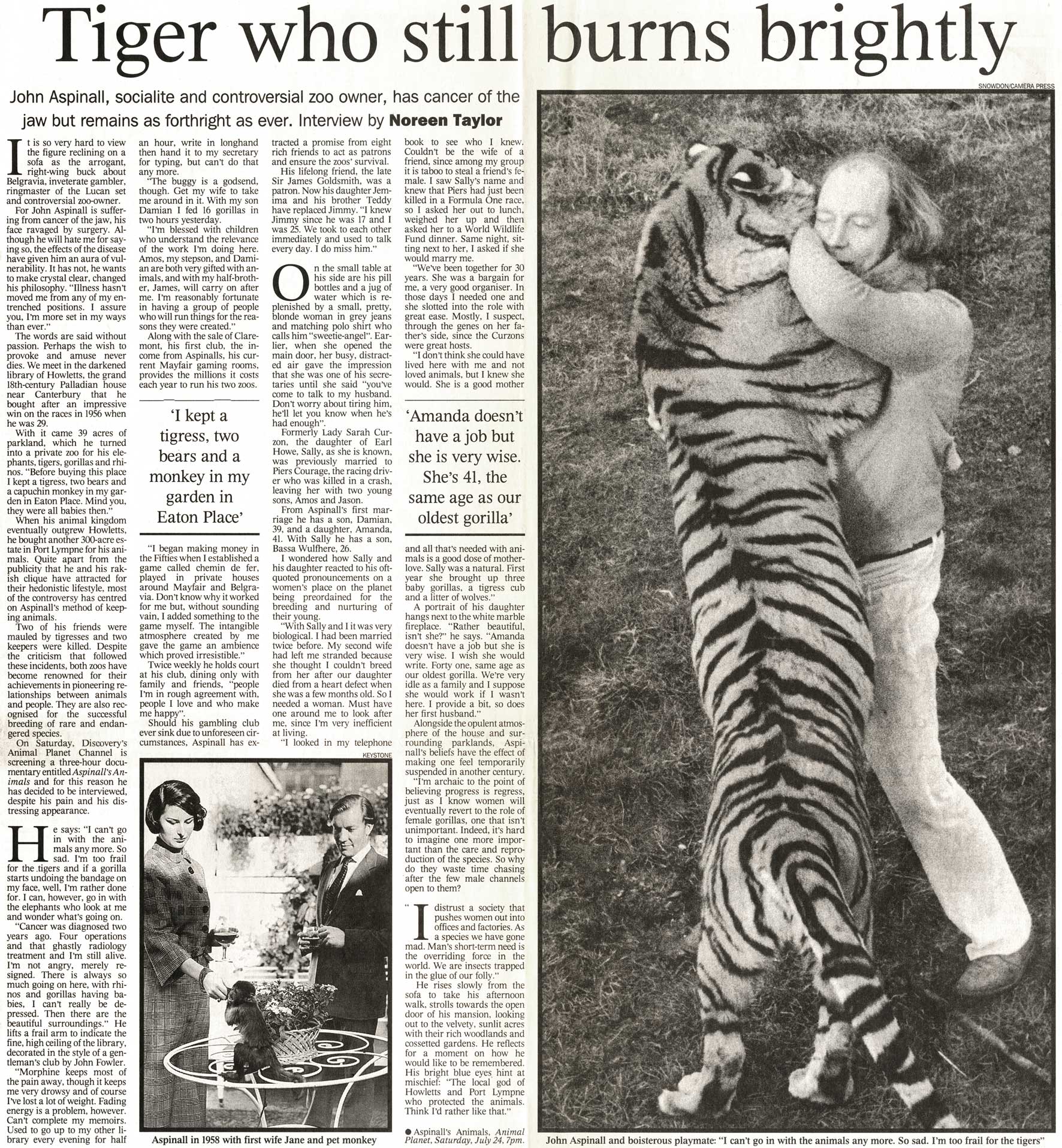

“Before buying this place I kept a tigress, two bears and a capuchin monkey in my garden in Eaton Place. Mind you, they were all babies then.” When his animal kingdom eventually outgrew Howletts, he bought another 300-acre estate in Port Lympne for his animals. Quite apart from the publicity that he and his rakish clique have attracted for their hedonistic lifestyle, most of the controversy has centred on Aspinall’s method of keeping animals.

Two of his friends were mauled by tigresses and two keepers were killed. Despite the criticism that followed these incidents, both zoos have become renowned for their achievements in pioneering relationships between animals and people. They are also recognised for the successful breeding of rare and endangered species.

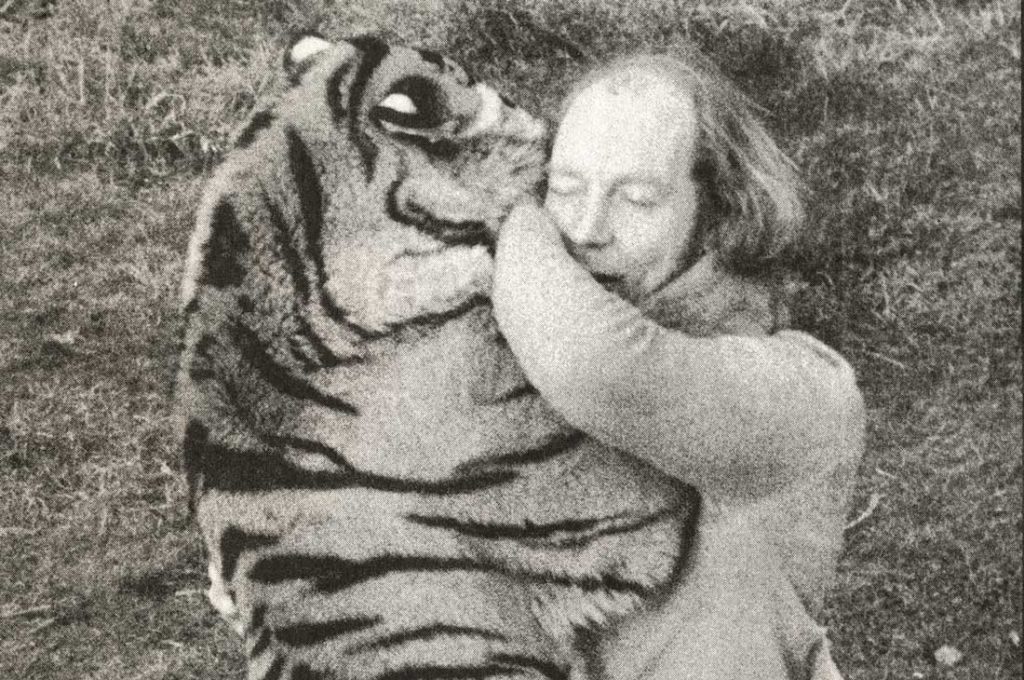

On Saturday, Discovery’s Animal Planet Channel is screening a three-hour documentary entitled Aspinall’s Animalsand for this reason he has decided to be interviewed, despite his pain and his distressing appearance. He says: “I can’t go in with the animals any more. So sad. I’m too frail for the tigers and if a gorilla starts undoing the bandage on my face, well, I’m rather done for. I can, however, go in with the elephants who look at me and wonder what’s going on.”

Cancer was diagnosed two years ago. “Four operations and that ghastly radiology treatment and I’m still alive. I’m not angry, merely resigned. There is always so much going on here, with rhinos and gorillas having babies, I can’t really be depressed. Then there are the beautiful surroundings.”

He lifts a frail arm to indicate the fine, high ceiling of the library, decorated in the style of a gentleman’s club by John Fowler. “Morphine keeps most of the pain away, though it keeps me very drowsy and of course I’ve lost a lot of weight. Fading energy is a problem, however. Can’t complete my memoirs. Used to go up to my other library every evening for half an hour, write in longhand then hand it to my secretary for typing, but can’t do that any more.

“The buggy is a godsend, though. Get my wife to take me around in it. With my son Damian I fed 16 gorillas in two hours yesterday. I’m blessed with children who understand the relevance of the work I’m doing here. Amos, my stepson, and Damian are both very gifted with animals, and with my half-brother, James, will carry on after me. I’m reasonably fortunate in having a group of people who will run things for the reasons they were created.”

Along with the sale of Claremont, his first club, the income from Aspinalls, his current Mayfair gaming rooms, provides the millions it costs each year to run his two zoos. “I began making money in the Fifties when I established a game called chemin de fer, played in private houses around Mayfair and Belgravia. Don’t know why it worked for me but, without sounding vain, I added something to the game myself. The intangible atmosphere created by me gave the game an ambience which proved irresistible.”

Twice weekly he holds court at his club, dining only with family and friends, “people I’m in rough agreement with, people I love and who make me happy.” Should his gambling club ever sink due to unforeseen circumstances, Aspinall has extracted a promise from eight rich friends to act as patrons and ensure the zoos’ survival.

His lifelong friend, the late Sir James Goldsmith, was a patron. Now his daughter, Jemima and his brother Teddy have replaced Jimmy. “I knew Jimmy since he was 17 and I was 25. We took to each other immediately and used to talk every day. I do miss him.”

On the small table at his side are his pill bottles and a jug of water which is replenished by a small, pretty, blonde woman in grey jeans and matching polo shirt who calls him “sweetie-angel.” Earlier, when she opened the main door, her busy, distracted air gave the impression that she was one of his secretaries until she said “you’ve come to talk to my husband. Don’t worry about tiring him, he’ll let you know when he’s had enough.”

Formerly Lady Sarah Curzon, the daughter of Earl Howe, Sally, as she is known, was previously married to Piers Courage, the racing driver who was killed in a crash, leaving her with two young sons, Amos and Jason. From Aspinall’s first marriage he has a son, Damian, 39, and a daughter, Amanda, 41. With Sally he has a son, Bassa Wulfhere, 26.

I wondered how Sally and his daughter reacted to his oft-quoted pronouncements on a women’s place on the planet being preordained for the breeding and nurturing of their young. “With Sally and I it was very biological. I had been married twice before. My second wife had left me stranded because she thought I couldn’t breed from her after our daughter died from a heart defect when she was a few months old. So, I needed a woman.

“Must have one around me to look after me, since I’m very inefficient at living. I looked in my telephone book to see who I knew. Couldn’t be the wife of a friend, since among my group it is taboo to steal a friend’s female. I saw Sally’s name and knew that Piers had just been killed in a Formula One race, so I asked her out to lunch, weighed her up and then asked her to a World Wildlife Fund dinner. Same night, sitting next to her, I asked if she would marry me. We’ve been together for 30 years.

“She was a bargain for me, a very good organiser. In those days I needed one, and she slotted into the role with great ease. Mostly, I suspect, through the genes on her father’s side, since the Curzons were great hosts. I don’t think she could have lived here with me and not loved animals, but 1 knew she would. She is a good mother and all that’s needed with animals is a good dose of mother love. Sally was a natural. First year she brought up three baby gorillas, a tigress cub and a litter of wolves.”

A portrait of his daughter hangs next to the white marble fireplace. “Rather beautiful, isn’t she?” he says. “Amanda doesn’t have a job but she is very wise. I wish she would write. Forty-one, same age as our oldest gorilla. We’re very idle as a family and I suppose she would work if I wasn’t here. I provide a bit, so does her first husband.”

Alongside the opulent atmosphere of the house and surrounding parklands, Aspinall’s beliefs have the effect of making one feel temporarily suspended in another century. “I’m archaic to the point of believing progress is regress, just as I know women will eventually revert to the role of female gorillas, one that isn’t unimportant.

“Indeed, it’s hard to imagine one more important than the care and reproduction of the species. So why do they waste time chasing after the few male channels open to them? I distrust a society that pushes women out into offices and factories. As a species we have gone mad. Man’s short-term need is the over-riding force in the world. We are insects trapped in the glue of our folly.”

He rises slowly from the sofa to take his afternoon walk, strolls towards the open door of his mansion, looking out to the velvety, sunlit acres with their rich woodlands and cossetted gardens. He reflects for a moment on how he would like to be remembered. His bright blue eyes hint at mischief:

“The local god of Howletts and Port Lympne who protected the animals. Think I’d rather like that.”