Susan Greenfield | The Times | February 2000

Susan Greenfield’s curriculum vitae would plunge the ordinary workaholic into the darkest of depressions.

Susan Greenfield’s curriculum vitae would plunge the ordinary workaholic into the darkest of depressions.

Culled from the many sheets faxed to me listing her work and achievements, here are the barest bones: Professor of Pharmacology at Oxford University; first female director of the Royal Institution; president of the Association for Science Education; leader of the science research group that has recently patented a brain molecule thought to hold the key to a cure for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s; recipient of a CBE, awarded in the latest New Year’s Honours List; regular radio broadcaster on her specialist subject, the human brain.

The catalogue of diplomas, degrees, trusteeships, fellowships and various scientific achievements of the nation’s best-known neuroscientist is awesome. Her work rate, and her success rate, is phenomenal. She has written seven books explaining the mechanics of the brain, the fifth of which, The Human Brain: A GuidedTour,became a bestseller.

Voted 14th most inspirational woman in the country by Harpers & Queenand 122nd most powerful person according to a Sunday newspaper list, she was once asked how she liked to relax. Her reply – “sorting through the sock drawer at weekends” – is typical of her easy sense of humour. The point, I suspect, was to neutralise the reputation she has acquired for being overly ambitious. So uncool, so un-Oxford.

This June, she is likely to increase her public recognition by presenting an important six-part science series on BBC2. You can almost hear the tabloid tags: television’s sexy boffin, the Charlie Dimmock of the laboratory.

The series will give her detractors in the rarefied world of academic science even more to grumble about. Apparently, scientists can be as bitchy as a dressing-roomful of starlets. Rivals are said to view her as a flash Madam Mega-Ambition, outwitting and out-starring all in her firmament. Can you imagine their reaction when she posed for Hello?

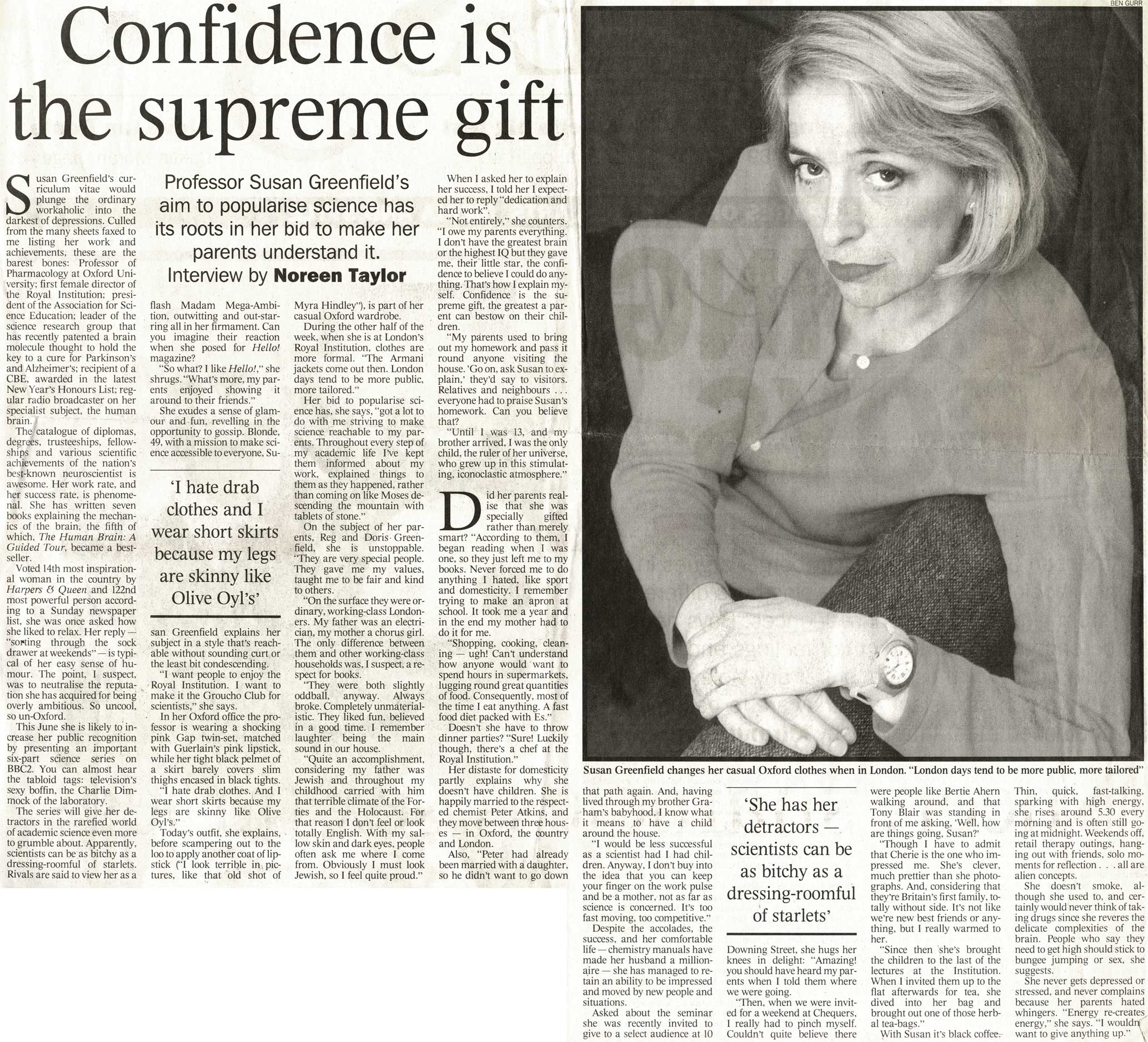

“So what? I like Hello” she shrugs. “What’s more, my parents enjoyed showing it around to their friends.” She exudes a sense of glamour and fun, revelling in the opportunity to gossip. Blonde, 49, with a mission to make science accessible to everyone, Susan Greenfield explains her subject in a style that’s reachable without sounding curt or the least bit condescending.

“I want people to enjoy the Royal Institution. I want to make it the Groucho Club for scientists,” she says. In her Oxford office the professor is wearing a shocking pink Gap twin-set, matched with Guerlain’s pink lipstick, while her tight black pelmet of a skirt barely covers slim thighs encased in black tights.

“I hate drab clothes. And I wear short skirts because my legs are skinny like Olive Oyl’s.” Today’s outfit, she explains, before scampering out to the loo to apply another coat of lipstick (“I look terrible in pictures, like that old shot of Myra Hindley”) is part of her casual Oxford wardrobe.

During the other half of the week, when she is at London’s Royal Institution, clothes are more formal. “The Armani jackets come out then. London days tend to be more public, more tailored.”

Her bid to popularise science has, she says, “got a lot to do with me striving to make science reachable to my parents. Throughout every step of my academic life I’ve kept them informed about my work, explained things to them as they happened, rather than coming on like Moses descending the mountain with tablets of stone.”

On the subject of her parents, Reg and Doris Greenfield, she is unstoppable. “They are very special people. They gave me my values, taught me to be fair and kind to others. On the surface they were ordinary, working-class Londoners. My father was an electrician, my mother a chorus girl. The only difference between them and other working-class households was, I suspect, a respect for books.

“They were both slightly oddball, anyway. Always broke. Completely unmaterialistic. They liked fun, believed in a good time. I remember laughter being the main sound in our house. Quite an accomplishment, considering my father was Jewish and throughout my childhood carried with him that terrible climate of the Forties and the Holocaust. For that reason, I don’t feel or look totally English. With my sallow skin and dark eyes, people often ask me where I come from. Obviously, I must look Jewish, so I feel quite proud.”

When I asked her to explain her success, I told her I expected the usual ‘dedication and hard-work’. “Not entirely,” she counters. “I owe my parents everything. I don’t have the greatest brain or the highest IQ, but they gave me, their little star, the confidence to believe I could do anything.

“That’s how I explain myself. Confidence is the supreme gift, the greatest a parent can bestow on their children. My parents used to bring out my homework and pass it round anyone visiting the house. ‘Go on, ask Susan to explain,’ they’d say to visitors, relatives and neighbours… everyone had to praise Susan’s homework. Can you believe that?

“Until I was 13, and my brother arrived, I was the only child, the ruler of her universe, who grew up in this stimulating, iconoclastic atmosphere.” Did her parents realise that she was specially gifted rather than merely smart? “According to them, I began reading when I was one, so they just left me to my books.

“Never forced me to do anything I hated, like sport and domesticity. I remember trying to make an apron at school. It took me a year and in the end my mother had to do it for me. Shopping, cooking, cleaning – ugh! Can’t understand how anyone would want to spend hours in supermarkets, lugging round great quantities of food.

“Consequently, most of the time I eat anything. A fast food diet packed with Es.” Doesn’t she have to throw dinner parties? “Sure! Luckily though, there’s a chef at the Royal Institution.”

Her distaste for domesticity partly explains why she doesn’t have children. She is happily married to the respected chemist Peter Atkins, and they move between three houses – in Oxford, the country and London. “Also, Peter had already been married with a daughter, so he didn’t want to go down that path again. And, having lived through my brother Graham’s babyhood, I know what it means to have a child around the house.

“I would be less successful as a scientist had I had children. Anyway, I don’t buy into the idea that you can keep your finger on the work pulse and be a mother, not as far as science is concerned. It’s too fast moving, too competitive.”

Despite the accolades, the success, and her comfortable life — chemistry manuals have made her husband a millionaire — she has managed to retain an ability to be impressed and moved by new people and situations. Asked about the seminar she was recently invited to give to a select audience at 10, Downing Street, she hugs her knees in delight:

“Amazing! you should have heard my parents when I told them where we were going. Then, when we were invited for a weekend at Chequers, I really had to pinch myself. There were people like Bertie Ahern walking around, and Tony Blair was standing in front of me asking, ‘Well, how are things going, Susan?’

“Though I have to admit that Cherie is the one who impressed me. She’s clever, much prettier than she photographs. And, considering that they’re Britain’s first family, totally without side. It’s not like we’re new best friends or anything, but I really warmed to her.

“Since then she’s brought the children to the last of the lectures at the Institution. When I invited them up to the flat afterwards for tea, she dived into her bag and brought out one of those herbal tea-bags.”

With Susan it’s black coffee. Thin, quick, fast-talking, sparking with high energy, she rises around 5.30 every morning and is often still going at midnight. Weekends off, retail therapy outings, hanging out with friends, solo moments for reflection… all are alien concepts.

She doesn’t smoke, although she used to, and certainly would never think of taking drugs since she reveres the delicate complexities of the brain. “People who say they need to get high should stick to bungee jumping or sex,” she suggests.

She never gets depressed or stressed, and never complains because her parents hated whingers. “Energy re-creates energy,” she says. “I wouldn’t want to give anything up.”